People living in Vietnam today may still feel the effects of the war. Kylie Nicholson/shutterstock.com

History often focuses on the immediate death toll of war. But hostilities can have longer-term consequences on a population’s health.

In our new study published on June 5, we investigated how U.S. Air Force bombing in Vietnam during 1965 to 1975 affected disability rates in Vietnam in 2009.

Using a combination of national census and U.S. military data, we found a causal link between wartime bombing and disability rates 40 years after the Vietnam War.

Our work, completed with Nguyen Viet Cuong at National Economics University in Vietnam and Daniel Mont at University College London, shows that wars inflict harms on the health of human populations that last for generations.

Bombings and disability

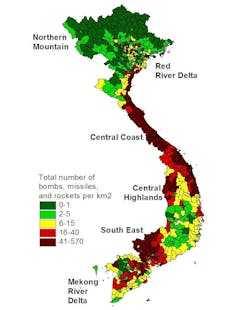

Our study looked at 14.2 million people across Vietnam. Approximately 8% of the population has a disability based upon an internationally tested measure of disability, including difficulties with seeing, hearing, walking and cognition.

As we expected, districts that were heavily bombed still have significantly higher disability rates 40 years later.

Injuries and impairments sustained among people directly exposed to the bombing are not surprising. Walking the streets of Ho Chi Minh City, one can see the high number of elderly amputees, whose injuries likely stemmed from the war.

However, war may have other, hidden effects on the health of populations, including among people born after the war.

In our study, we looked more closely at the total number of bombs, missiles and rockets per square kilometer, and how that related to the proportion of people with disability at different ages.

In districts with high levels of bombing, disability rates were highest for people around 40 years of age, the group born in the late 1960s during the heaviest level of wartime bombing.

However, perhaps surprisingly, there also seems to be a relationship between the bombings and those born as long as 15 years after the war. In districts that saw more bombings, Vietnamese people born before around 1990 have higher rates of disability than those in other parts of the country.

As one New York Times story noted, since the end of the war, more than 67,000 Vietnamese have been maimed by unexploded cluster bombs, losing limbs or eyes. Around 40,000 have lost their lives in such accidents.

Preventing further damage

It is difficult to disentangle exactly why bombing has these long-term effects on disability.

A likely explanation is that people in heavily bombed areas continue, many years later, to suffer from direct exposure to the bombing and connected weaponry, including unexploded bombs, landmines and military herbicides more commonly known as Agent Orange.

People in areas that were heavily bombed are more likely to experience poor nutrition in childhood and have lower education. This, too, may indirectly cause long-term disability.

In Vietnam, health care services for the disabled – such as rehabilitation and assistive devices like prostheses, wheelchairs and hearing devices – are limited in supply and quality.

To us, our findings underscore the importance of all parties involved in the war expediting the process of cleaning up the consequences and ensuring food security and adequate health services for people in conflict-affected zones.

Cleaning up the consequences of war is usually led by the government of the country, along with support from international donors like the U.N. In Vietnam, U.S. assistance has been slow to materialize. Funding support from the U.S. started in 1993. U.S. humanitarian assistance to Vietnam has been increasing over the last decade, but is under threat under the current Trump administration.

The toll of warfare is often assessed in terms of the number of people killed. However, we feel that warfare’s lasting and intergenerational consequences on health is an underacknowledged problem. The ravages of war extend far beyond the years it was waged.![]()

Michael Palmer, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Western Australia; Nora Groce, Director UCL International Disability Research Centre, UCL, and Sophie Mitra, Professor of Economics, Fordham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.