Hong Kong protesters shelter behind a thin barrier – and umbrellas – as police fire tear gas and encircle a group of demonstrators. AP Photo/Vincent Yu

Hong Kong may seem like an unlikely place for a revolution. In this relatively affluent and privileged city, young people might be expected to be more concerned with making money than with protesting in the streets. Yet day after day, demonstrators in Hong Kong risk injury and death confronting security forces backed by the massive power of the Chinese government.

Among their demands are democratic elections for the city’s Legislative Council and chief executive. Their desire for fundamental change has mounted, and they increasingly see their own lives as lacking meaning unless circumstances change.

Historians have long argued that revolutions are built not on deep misery but on rising expectations. Since the 18th century, societies, clubs and associations of intellectuals have been seedbeds of radical change in countries throughout the world. They provided leadership for the French Revolution in 1789, the European revolutions of 1848 and the Russian Revolution of 1905.

The situation in Hong Kong is revolutionary, too, although the history of past revolutions may not provide much hope of immediate change.

A look at Hungary

The most compelling parallel to Hong Kong may be the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, which attempted to wrest power from a communist regime. It, too, began with a student uprising in favor of democratic elections.

Within a few days, the communist government resigned and a reformist administration was formed under Imre Nagy, who allowed noncommunists to enter political office. This went too far for communist leaders in the Soviet Union. The USSR invaded Hungary, overthrew Nagy’s regime and secretly put him to death.

As with the Hong Kong protests today, the United States gave little official support to the Hungarian Revolution and was unwilling to offer material assistance. Keeping peace in Europe was of vital importance to U.S. policy in 1956, just as good relations with China are now central.

The Hungarian example may provide little solace to the Hong Kong protesters – except, perhaps, if they consider its long-term consequences.

In October 1989, with Soviet influence in Eastern Europe collapsing, the democratic Republic of Hungary was declared on the 33rd anniversary of the 1956 revolution. Those who died during that revolution are now remembered as martyrs.

In China’s own history

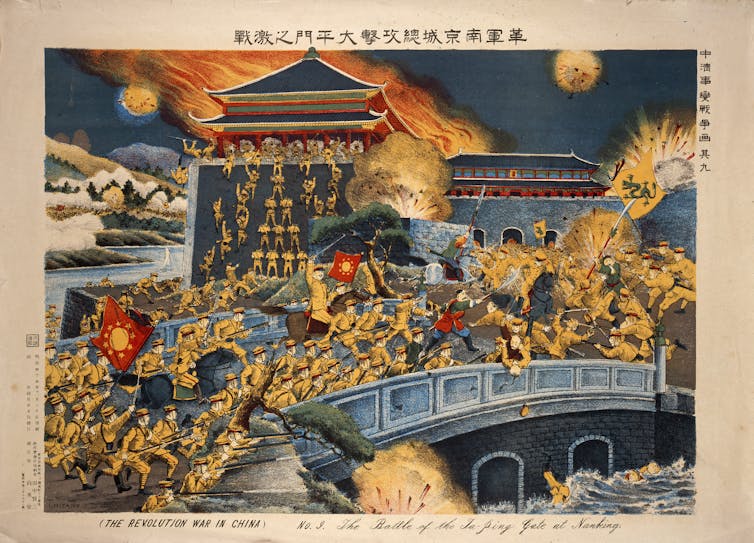

Chinese history supplies a more heartening example of a successful student-led uprising: the Revolution of 1911. It was fomented by young men returning from study abroad, who formed political societies to “revive” their country, often disguised as literary discussion groups.

The 1911 Revolution mobilized networks of intellectuals and students throughout China, but it also drew on other social groups: military officers, merchants, coal miners and farmers. The revolution erupted in many parts of China simultaneously and had various outcomes, from utter failure, to the massacre of ethnic Manchus to declarations of Mongol and Tibetan independence. A provisional government emerged by the end of the year in Nanjing.

The Hong Kong protests, however, are too limited in geographical scope and social support to repeat the success of the 1911 revolutionaries.

The subsequent Chinese revolution in 1949, like the 1917 Russian Revolution, followed Leninist theory and was spearheaded by professional party insiders, not by intellectuals. The communists regarded mass protests as potentially counter-revolutionary and as threats to the new order.

What’s next?

The young protestors in Hong Kong seek to avoid the fate of the student demonstrators of Tiananmen Square in spring 1989. Three decades ago, hundreds, perhaps thousands, of protesters were massacred after the communist government invoked martial law. The pro-democracy agenda of the Tiananmen protesters was vague, and they relied on reformers within the party apparatus, who finally betrayed them.

The Hong Kong crowds are focused on specific changes and lack illusions about the party. They will go down fighting desperately, not standing with faint hope in front of tanks. That may give pause to the forces of repression. As the Communist Party of China and any student of history knows, martyrs are the fuel of future revolutions.

Paul Monod, Professor of History, Middlebury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.