The bombing of Gaza may have ended, the sirens in Tel Aviv silenced for now. Yet as concern over a planned June 15, 2021 march by right-wing Israeli nationalists underscores, the threat of violence in Israel is never far from the surface. It is sustained and fueled by what is at the core of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict: land and property ownership.

A key component in the most recent violence – 11 days in which 282 Palestinians were killed by Israeli bombs or bullets and 13 Israelis killed by Hamas rockets from Gaza – was tension following efforts by Jewish settlers to evict Palestinians from their homes in the urban neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah in occupied East Jerusalem.

The Israeli government has said that these evictions were the result of a “real-estate dispute between private parties” without indicating a historical precedent.

But as a scholar of the Ottoman Empire, which ruled over Palestine from 1517 to 1919, I argue that these disputes are not private quarrels taking place in the here and now. Rather, they reflect a history of land disputes that have long defined the terms of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. It is seen in the repression of legal claims over agricultural land in the late 19th century, and continues with the selective denial of Palestinian claims for urban spaces today.

Property in Ottoman Palestine

Landed property has long been a crucial part of Zionism – a settler colonial movement that pushed for the establishment, and then support, of a Jewish state. In practice, this has meant the dispossession of land from the Palestinian Arab population.

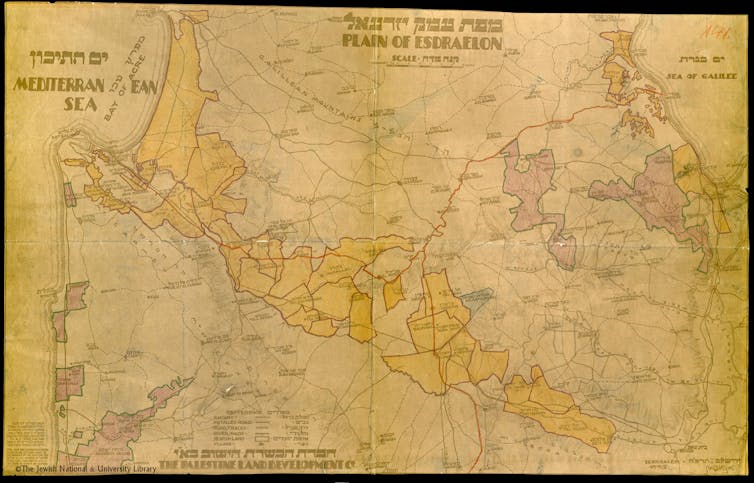

From the 1901 founding of the Jewish National Fund – an organization that purchased agricultural land for a future Jewish homeland – Zionists’ goal was to purchase contiguous villages in what was then the plains of Ottoman Palestine. Zionists targeted an N-shaped area that took in the most fertile land in the region. This N-shaped settlement became a template for the 1947 U.N. partition plan for Palestine and the core of the future Israeli state after the Arab-Israeli War of 1948.

The lands that Zionist organizations targeted for purchase were primarily held by companies headed by families living in the Levant – the Sursuqs, Bustruses, Debbases, Trads, Khuris, Hajjars and Tueinis. These family companies, whose owners were living in Cairo and Beirut, became major global capitalist enterprises during the 19th century, investing in manufacturing and trade in India, Germany and Britain.

The narrative pushed by many Zionists – both in the early 20th century and today – is that the land was empty of people and in the hands of Levantine absentee landlords.

But ownership of the land was a murkier affair, with more than one claimant.

In the mid-19th century, agricultural land in the Ottoman Empire was technically state-owned. Levantine companies and peasants purchased the right to use the land from the Ottoman government or from local sellers. Peasants had bought and sold these use rights as if they owned the land itself since at least the 18th century. The Ottoman state also recognized Palestinian Arab peasants, merchants and Bedouin as owners of olive groves, fruit trees, mills, houses, buildings, and even water and grazing rights on this land.

These multiple claims complicated attempts to sell land to Zionists. The Levantine companies didn’t have enough land solely in their ownership to satisfy Zionist demand and local Ottoman officials and courts blocked the Jewish purchasing agencies’ demands for private property.

Dispossession during World War I

Frustrated by their inability to sell and buy entire villages, the Levantine companies and their Zionist partners took advantage of World War I to dispossess Palestinians of some of their property rights.

During the war, the Ottoman Empire was subjected to a lengthy naval blockade that led to a severe food shortage. To satisfy the demand for food for soldiers, Levantine companies under the supervision of the Ottomans diverted wheat from fertile regions of Palestine to give to the military – resulting in starvation and impoverishment among Palestinians.

With peasants unable to pay taxes, Ottoman leaders – under pressure from capitalist families in Beirut – took away peasants’ rights to land and gave temporary rights to the Levantine companies for growing food.

When the British were handed the mandate for the administration of Palestine at the end of the war, its officials upheld Levantine companies’ claims to the land, ignoring Palestinians who came forward with their own ownership claims to land, buildings and homes.

Palestinians continued to present paperwork that supported their case throughout the period up to 1948, but by then much of the land they were disputing had become exclusively Zionist-owned.

It had been sold to them by the Levantine companies, attracted by the Zionists’ offers to buy villages for well over the market value.

Both the Zionist buyers and Levantine companies knew that many Palestinian Arabs still owned homes, olive groves, mills, warehouses and fields in the N-shaped region. They offered money to the families that came forward. But, Zionists forcibly evicted them if they refused compensation or to sell their land.

My research has found that Palestinians repeatedly brought ownership claims to British courts. But there is evidence that the claims were hampered by the claimants’ difficulty accessing the courts. In addition, the Levantine companies manipulated official land records during World War I to expand their boundaries and eliminate others’ claims to parts of villages.

Even if they suspected the transactions were unclean, British officials honored the land titles exchanged between the politically powerful Levantine companies and Zionists.

After the 1948 Arab-Israeli War – an event in which Jewish forces displaced approximately 750,000 Palestinians from their homes in Palestine – the 1950 Absentee Land Laws prohibited Israel’s consideration of any more Palestinian claims for the land Israel occupied before and during the 1948 war.

Disputes and evictions

Recent events show that these land disputes are not just a matter of history. The dispute over Sheikh Jarrah involves claims that Jewish settlers acquired land rights in 1885. Palestinian families say that it was Palestinian-owned long before then.

To describe dispossessions in Sheikh Jarrah as a “real estate” quarrel conceals the true history of land ownership in the regions – which is complicated, disputed and rarely decided in favor of Palestinians.![]()

Kristen Alff, Assistant Professor, North Carolina State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.