Global shipping is constrained by geography.

Massive oil tankers and cargo ships – carrying over 90 percent of global trade flows by weight – converge in narrow straits. The result: The world’s key shipping lanes are often crowded.

As a researcher who has focused on strategic maritime chokepoints for over 15 years, I appreciate the vital importance of these waterways – not only economically, but also politically.

This geostrategic significance came into fresh focus when Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani recently threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz following the Trump administration’s decision to leave the Iran nuclear deal.

What is the Strait of Hormuz?

The Strait of Hormuz is one of the world’s key maritime chokepoints.

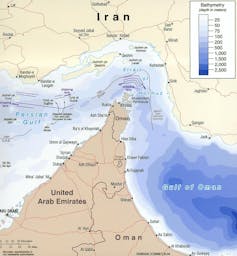

This narrow seaway connects the Indian Ocean with the Arabian/Persian Gulf. For all of recorded history, the seaway has connected Arab and Persian civilizations with the Indian subcontinent, Pacific Asia and the Americas. For example, before the rise of European seaborne empires in the 15th and 16th centuries, porcelain from China and spices from the Indochina peninsula often passed through the strait on their way to Central Asia and Europe.

Today the Strait of Hormuz separates the modern Iranian state from the countries of Oman and the United Arab Emirates, which have strong defense connections with the United States and Saudi Arabia.

All shipping traffic from energy-rich Gulf countries converges in the strait, including crude oil and liquefied natural gas exports from Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Thirty percent of the world’s crude oil flows through this 21-mile wide waterway.

This maritime chokepoint became an arena of conflict during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s. Each side in the so-called “Tanker War” tried to sink the other’s energy exports. To avoid being targeted, Kuwaiti oil tankers were reflagged under the U.S. shipping registry. Although crude oil continued to flow, marine insurance rates for vessels operating in the strait spiked by as much as 400 percent. Those higher costs likely contributed to higher gasoline and diesel prices worldwide.

What is happening now?

So are American consumers likely to suffer because of Rouhani’s threat?

Iran does not need superior military strength to fulfill its threat to disrupt trade flows through the strait. It could damage commercial shipping with relatively cheap anti-ship missiles, fast patrol boats, submarines and mines.

But analysis from Admiral Dennis Blair and Kenneth Liberthal concluded that Iran would have trouble stopping all shipping through the strait. Modern cargo vessels are massive and difficult to disable. Unlike in the 1980s, most oil tankers now have double hulls, making them more difficult to sink.

![]() That said, even threats and modest disruption to commercial shipping could trigger economic damage in the form of higher marine insurance rates, crude oil supply concerns and unsettled stock markets.

That said, even threats and modest disruption to commercial shipping could trigger economic damage in the form of higher marine insurance rates, crude oil supply concerns and unsettled stock markets.

Rockford Weitz, Professor of Practice and Director of the Fletcher Maritime Studies Program, Tufts University This article was originally published on The Conversation.