Strict policies traditionally embraced by Asian nations to discourage illicit drug use are beginning to change, with a few nations adopting alternative approaches while other nations are taking an even harder line against drugs, according to a new RAND Corporation report.

Thailand is on the forefront of Southeast Asian nations that are reconsidering longstanding policies, moving to adopt greater harm reduction, approving the use of medical cannabis and easing restrictions on the traditional use of the substance kratom.

Meanwhile, some other nations — most visibly represented by the Philippines — are adopting even harsher policies on illicit drugs, including violent repression of drug distribution and use.

“Asian nations have long espoused the goal of a drug-free society, imposing harsh criminal penalties and even the death penalty on those involved with illicit drugs,” said Bryce Pardo, lead author of the report and a policy analyst at RAND, a nonprofit research organization. “So it is surprising to see some Asian nations begin to go in a different direction and consider more-progressive policies.”

The RAND report also dissects China’s role as a focal point in the global supply of fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that is responsible for a growing number of fatal drug overdoses in the U.S.

The report outlines the rapid rise of the drug industry in China, where there are now more than 5,000 pharmaceutical manufacturers and hundreds of thousands of chemical companies. While the industry is a leading source of many legitimate chemicals and pharmaceutical ingredients, its growth has made it easier for some companies to avoid regulations.

China’s central government has promised to crack down on fentanyl manufacturers, but enforcement of such policies is typically done at the provincial level, where there is little infrastructure in place to regulate the drug and chemical industries.

“China’s leaders recognize that they have a problem and appear committed to seeking solutions,” Pardo said. “But it is unlikely that they can contain the illicit production and distribution of fentanyl in the short term because enforcement mechanisms are lacking. Producers are quick to adapt, impeding Chinese law enforcement’s ability to stem the flow to global markets.”

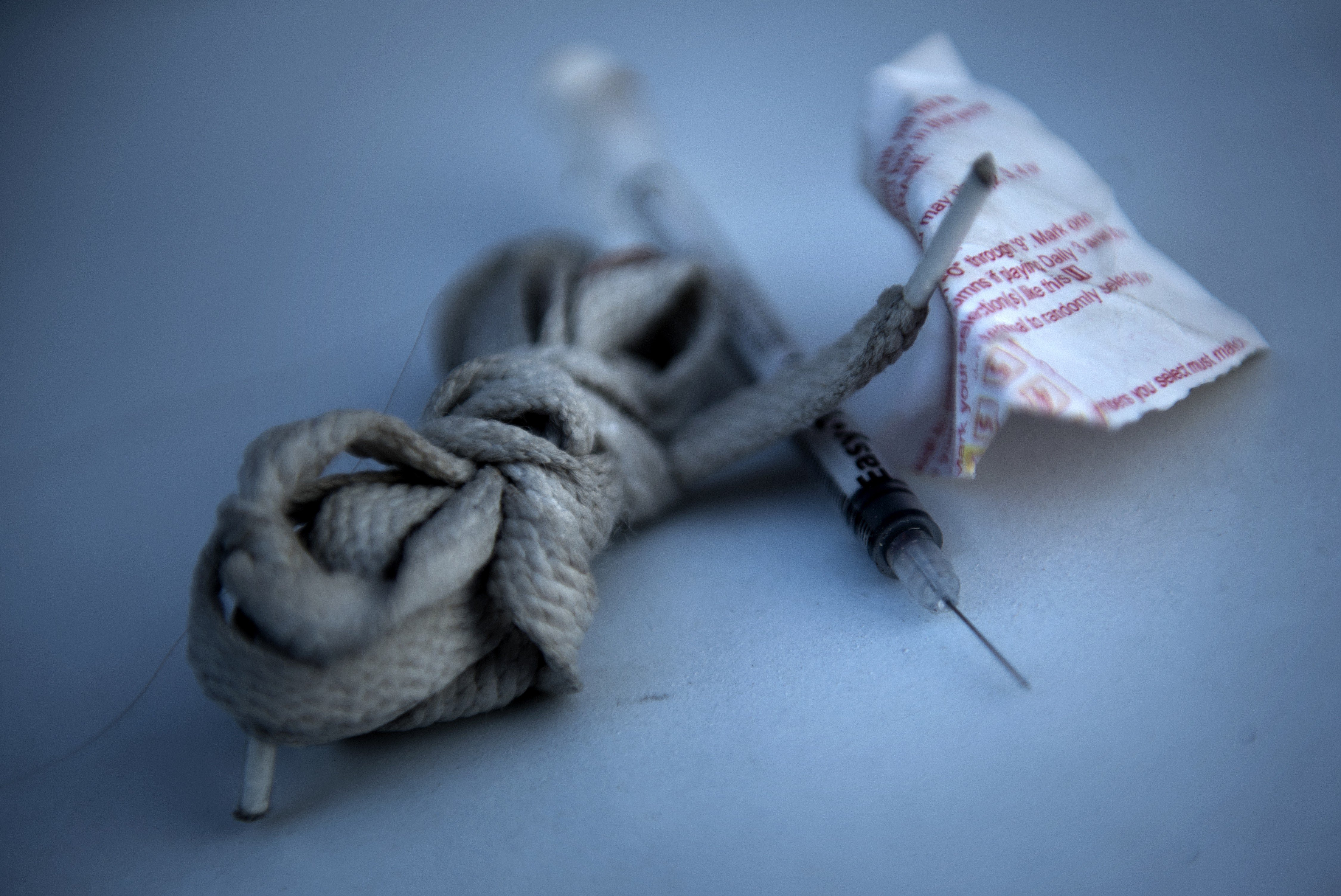

Thailand’s shift from harsh drug policies toward evidence-based treatment and reduced punishment appears to be motivated by the heavy burden previous policies have had on its prison system and an alarming increase in disease transmission related to needle-sharing.

In 2016, about 70 percent of Thailand’s 320,000 prisoners were incarcerated for drug offences, including many for consumption-related violations. The nation has begun to move toward voluntary outpatient treatment and has experimented with needle-exchange programs to address disease transmission.

The report notes that the illicit production and use of opioids and amphetamine-type substances are the greatest concern across Asia. There also are reports of rising trafficking and use of new psychoactive substances and ketamine.

But one challenge facing Asian nations is a shortage of reliable information about drug use, which is key to assessing the size of the problem and judging the influence of policies.

“As in many countries, there is tremendous imprecision in the data available on the prevalence of drug use in Asia and the amount of money spent on these substances,” said Beau Kilmer, a co-author of the report and co-director of the RAND Drug Policy Research Center. “Policy shifts are occurring and these data gaps will make it difficult to evaluate the consequences of these changes in the near and longer term.”