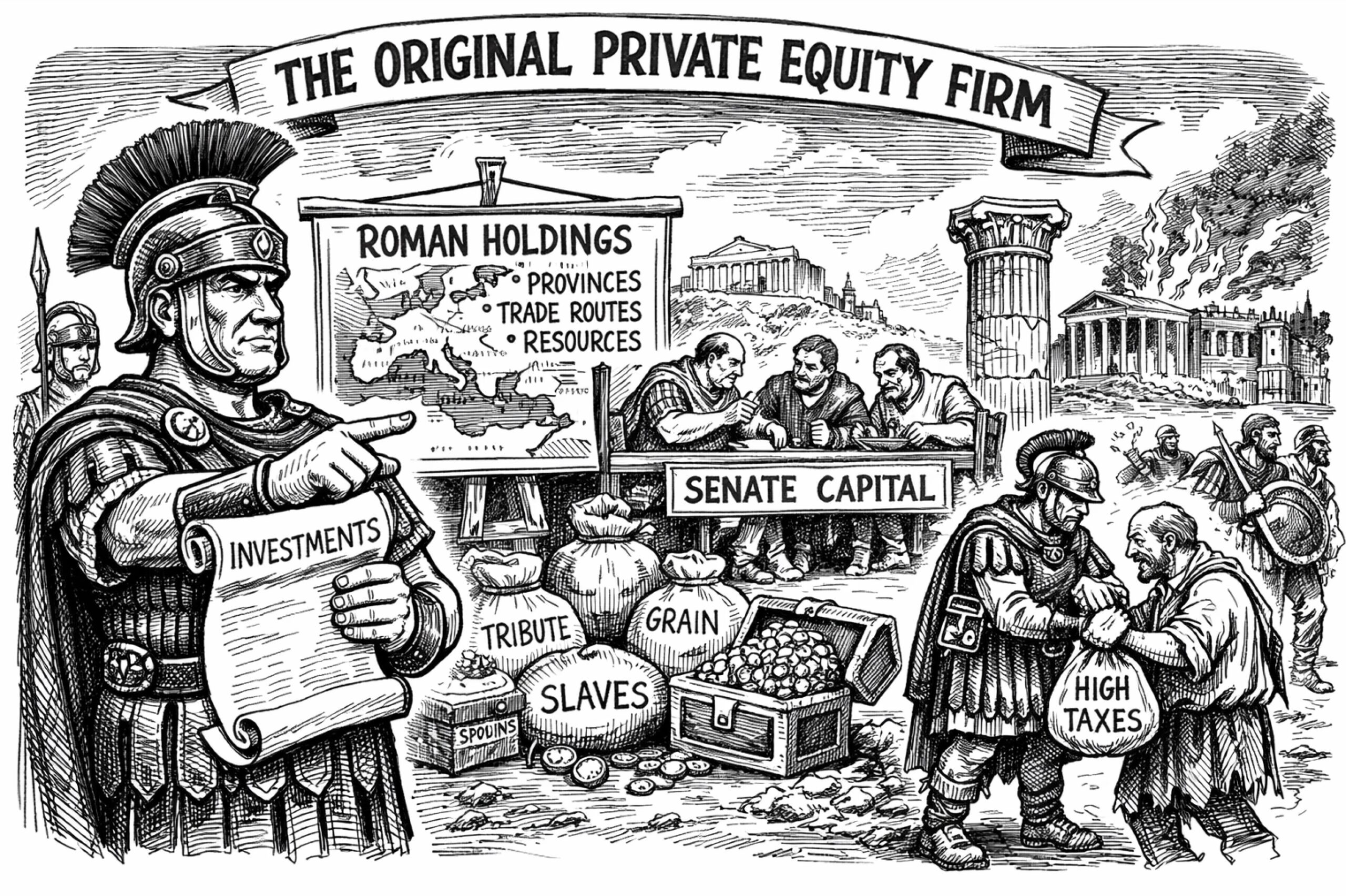

Rome, Incorporated: How the Ancient Republic Functioned Like the World’s First Private Equity Powerhouse and What Today’s Firms Should Learn from Its Rise and Fall

When modern observers describe private equity, they often invoke images of leveraged buyouts, activist investors, cross border acquisitions, and patient capital reshaping underperforming assets. Yet long before limited partners, carried interest, or deal books existed, the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire built a system that bore striking resemblance to a sprawling, state enabled investment platform.

When modern observers describe private equity, they often invoke images of leveraged buyouts, activist investors, cross border acquisitions, and patient capital reshaping underperforming assets. Yet long before limited partners, carried interest, or deal books existed, the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire built a system that bore striking resemblance to a sprawling, state enabled investment platform.

Rome expanded by deploying capital, manpower, and governance structures into foreign territories, extracting resources, tax revenues, and strategic advantage, then reinvesting those proceeds into further conquests and infrastructure. Its elites, senators, equestrians, contractors, and financiers, acted much like a tightly networked class of general partners. Provinces were, in effect, portfolio companies acquired through force or diplomacy, reorganized to maximize output, overseen by governors with broad discretion, and occasionally stripped when returns disappointed.

Rome offers more than an intriguing metaphor. Its centuries long ascent demonstrates how disciplined capital allocation, logistical superiority, legal innovation, and public private partnerships can create durable geopolitical and commercial dominance. Its eventual stagnation and fragmentation illustrate how over leverage, governance breakdowns, regulatory capture, and social backlash can undermine even the most formidable system.

In an era when American private equity commands trillions in assets and increasingly intersects with national security, infrastructure, energy, and industrial policy, Rome’s story reads less like ancient history and more like a cautionary case study.

Rome’s Investment Model: Conquest as Acquisition Strategy

Rome did not conquer blindly. Expansion followed recognizable investment logic. Military campaigns were expensive, but they were frequently justified and financed by the expectation of long term returns such as tribute, taxes, agricultural surpluses, mineral wealth, enslaved labor, and control of trade routes.

Once a territory was subdued, Rome rarely annihilated it. Instead, it installed a governance layer, standardized legal frameworks, and integrated local elites into its system. Roads, ports, aqueducts, and fortifications were constructed not merely as public works but as productivity multipliers that reduced transaction costs, accelerated troop movement, and facilitated commerce. The Roman road network functioned much like today’s logistics and data infrastructure, expensive upfront yet indispensable to scale.

Provinces were assessed for yield. Egypt supplied grain to feed the capital. Hispania produced silver and copper. Gaul generated agricultural surpluses and manpower. North Africa became an export engine for olive oil. Returns flowed to Rome in the form of taxes and contracts awarded to private operators.

This is where the analogy to private equity becomes particularly sharp.

Rome outsourced much of its provincial revenue collection and supply chains to publicani, private tax farming syndicates composed largely of the equestrian class. These firms bid for multi year contracts to collect taxes or provision armies, fronting capital in advance and retaining profits above the contracted amount. They were early versions of infrastructure funds and government services contractors rolled into one.

Risk was privatized. Reward was substantial.

The state provided military protection and legal enforcement. The investors provided liquidity, operational execution, and political influence. Together, they formed a proto financial ecosystem that blurred the line between public authority and private enterprise, much as today’s private equity firms often operate at the intersection of markets and policy.

Governance and Value Creation

Rome’s genius lay not only in acquisition but in post acquisition integration.

Citizenship was gradually extended to conquered peoples. Local laws were codified under Roman legal principles. Elites were co opted into the imperial system through land grants, trade privileges, and political advancement. These measures reduced rebellion, stabilized revenue streams, and aligned incentives in ways comparable to modern sponsors installing new management and governance frameworks in portfolio companies.

Oversight, at least in theory, came from magistrates and later imperial bureaucracies. Governors were expected to maintain order, stimulate production, and remit taxes. Successful administrators could build careers and fortunes while disastrous ones sometimes faced prosecution, though enforcement varied widely.

Rome also diversified its holdings. It controlled agricultural zones, mining districts, shipping hubs, and manufacturing centers across three continents. When one region faltered because of drought or unrest, others could compensate. This geographic and sectoral diversification cushioned shocks much as global funds spread exposure across industries and regions.

Financial innovation followed necessity. Complex partnerships, credit instruments, and insurance like arrangements emerged to underwrite long distance trade and military logistics. Roman law recognized corporations, contracts, and transferable shares in certain enterprises. These were the institutional rails on which empire scale capital flows traveled.

The Security and Commerce Nexus

Rome’s system highlights a reality that private equity increasingly confronts: economic power and geopolitical influence are inseparable.

Rome’s legions were not merely military units. They were stability enforcers for commercial networks. Garrisons protected mines, farms, and ports. Pirates were suppressed to secure shipping lanes. Frontier forts doubled as customs checkpoints.

In return, commercial profits helped finance military readiness. Victorious generals paid troops with spoils. Provincial taxes funded fortifications and fleets. The cycle of security enabling commerce and commerce funding security created a self reinforcing loop.

Modern parallels are unavoidable. Today’s private equity firms invest in defense manufacturing, logistics providers, energy infrastructure, data centers, ports, telecommunications, and semiconductor supply chains, assets that governments increasingly regard as strategic. Capital allocation decisions made in boardrooms can shape national resilience, technological leadership, and geopolitical leverage.

Rome demonstrates both the potency and the peril of such entanglement.

Over Extraction and the Seeds of Decline

If Rome resembled a private equity empire in ascent, its decline mirrors what happens when financial engineering overwhelms productive investment.

By the late Empire, the fiscal demands of maintaining borders, bureaucracies, and court politics soared. Tax burdens increased, particularly on small landholders, driving consolidation into massive estates owned by elites who wielded political clout to minimize their own obligations. Productive capacity stagnated even as extraction intensified.

Provincial governors and tax collectors, no longer tightly supervised, often stripped regions for short term gain. Infrastructure decayed. Coinage was debased to cover deficits, eroding trust in the monetary system and fueling inflation. Military spending consumed an ever larger share of resources while yields from expansion diminished.

This was, in effect, a shift from growth oriented investment to harvest mode.

Rome also struggled with succession planning and governance drift. Authority concentrated in emperors and court factions, weakening institutional checks. Corruption proliferated. Decision making slowed. Strategic flexibility declined. The system that had once rewarded competence increasingly rewarded proximity to power.

When external shocks arrived such as pandemics, climate fluctuations, migrating populations, and rival powers, the empire lacked the fiscal and administrative resilience that had characterized its earlier centuries.

Lessons for America’s Private Equity Class

Rome’s experience offers several hard headed insights for contemporary American private equity, particularly as it expands into sectors critical to national security and long term economic stability.

First, durable returns come from infrastructure and institutions, not just financial optimization. Rome’s roads, ports, and legal frameworks were not quick wins. They were patient, capital intensive projects that unlocked decades of growth. Private equity faces increasing scrutiny for short holding periods and aggressive cost cutting. Rome’s history suggests that long term value creation, especially in strategic industries, requires sustained reinvestment.

Second, alignment between state interests and private capital is powerful but dangerous. Rome flourished when public authority and private enterprise reinforced each other under clear rules. It faltered when elites captured the state to shield themselves from risk while continuing to extract value. For modern firms operating in regulated or security sensitive domains, legitimacy, transparency, and fair burden sharing are not public relations luxuries. They are strategic necessities.

Third, diversification and adaptability are existential. Rome’s early diversification across regions and resources made it resilient. Later rigidity in administration, taxation, and military posture made it brittle. American private equity faces technological disruption, geopolitical fragmentation, and regulatory flux. Funds that remain flexible in sector exposure, governance structures, and capital deployment will be better positioned to weather systemic shocks.

Fourth, restraint in leverage matters at the system level. Rome’s late imperial fiscal strategy relied increasingly on monetary manipulation and coercive taxation to sustain obligations. Modern private equity operates in an environment shaped by cheap credit cycles and complex financial engineering. History suggests that when leverage becomes a substitute for productivity growth, long term stability erodes.

Finally, legitimacy is a strategic asset. Rome maintained authority for centuries not only through force but through the perception that its system delivered order, prosperity, and opportunity to subject populations. When that legitimacy frayed, rebellions multiplied and compliance declined. In the United States, where public scrutiny of private equity is intensifying, firms that can demonstrate contributions to employment, innovation, and national resilience will enjoy greater political and social license to operate.

Rome did not think of itself as an investment firm, yet it constructed one of the most sophisticated capital allocation and extraction systems in history. Its blend of military power, legal standardization, infrastructure investment, and public private collaboration produced centuries of dominance across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East.

Its downfall was not sudden. It was the cumulative result of governance failures, fiscal overreach, elite capture, and declining reinvestment in productive capacity.

For America’s private equity class, the lesson is neither triumphalist nor fatalistic. Rome shows how disciplined expansion and institutional depth can build an empire of extraordinary durability. It also shows how even the most formidable systems can hollow themselves out if short term extraction replaces long term stewardship.

In a world where finance and security are increasingly intertwined, that is not merely an academic observation. It is a strategic warning.

– Use Our Intel