Warlords turn aid into a “cash machine.” To stop fueling wars, donors must enforce strict benchmarks and halt money when it’s stolen.

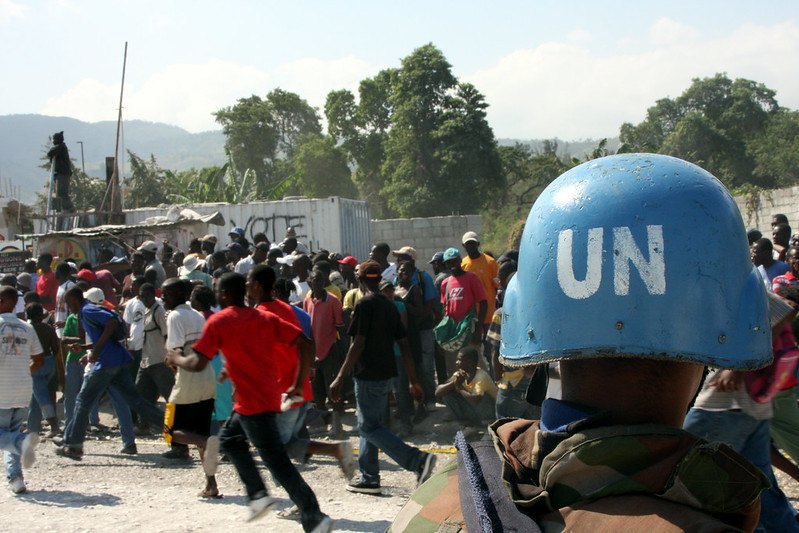

The pictures are heartbreaking: convoys of UN-marked trucks inching toward bomb-scarred cities, with desperate children clamoring for supplies. They seem to prove that the international system is, at the very least, trying to help. Yet in every conflict we have studied—Liberia, Sierra Leone, Goma, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Gaza—the same trucks double as cash machines for warlords, militias, and authoritarian regimes. Aid diversion is not the unfortunate by-product of the machinery of aid; it is the governing logic of humanitarian operations. Unless the United States and other top donors rewrite the rules so that aid cannot be separated from accountability, they will keep subsidizing the conflicts they abhor.

The Mechanics of Misery

The United Nations’ four core humanitarian principles—humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence—sound noble, but only the first principle guides actual operations on the ground. Consider Somalia, where three interclan cartels were paid hundreds of millions of dollars every year in World Food Program (WFP) transport contracts, and skimmed 30 to 50 percent of the cargo. Once the cargo is delivered to camps for internally displaced persons, it must pass through “gatekeepers” who collect the aid on behalf of both genuine refugees, family members of local armed groups, and entirely fictitious individuals. Fewer than half of registered beneficiaries were found to actually exist, with militias and other local power brokers often registering their own dependents. Genuine beneficiaries were found to be taxed by “gatekeepers” controlling the camps up to half of the received aid. Overall, only a fraction of the aid reached its intended beneficiaries.

In Syria, then-President Bashar al-Assad insisted that all international aid operate in the local currency, exchanged at a government-set rate at barely half the actual exchange rate. That simple accounting trick handed Damascus at least $60 million in 2020 alone—more than the country’s annual budget for cancer care. At the same time, Assad designated the opposition-held districts as “unsafe,” preventing aid convoys from reaching them and directing them instead to districts controlled by Assad loyalists.

Afghanistan shows how quickly diversion professionalizes. What began in the 1980s as Mujahideen commanders pocketing refugee rations is now a Taliban finance commission that typically levies 10 to 15 percent on most aid imports and prints tax receipts. Donor states’ dollars thus bankroll the same regime that state donors sanction.

In Yemen, Houthi rebels formalized a 2 percent levy on every aid dollar, kidnapped more than two dozen UN staffers in order to enforce compliance and renegotiate terms in their favor, and looted aid warehouses whenever negotiations stalled. Even after a brief WFP suspension this year, aid groups reported that ration bags stamped “Not for Sale” resurfaced in Sana’a markets within 72 hours.

Meanwhile, Sudan’s warring factions have turned diesel donated for aid trucks into a commodity worth fighting over: Hundreds of thousands of liters vanished from an El Obeid depot and were later repurchased—by the UN—at five times the original price. The country’s first famine declaration in two decades followed weeks later.

Ethiopia demonstrates what happens when donors finally balk. Workers with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) discovered that their partner, the WFP, was colluding in “industrial-scale” theft by the Ethiopian military. Entire flour mills stuffed with USAID-donated wheat were diverted to Ethiopia’s army. Subsequently, Washington paused food aid nationwide. Within months, diversion dropped, and the Ethiopian government begrudgingly accepted electronic tracking of the aid shipments. The lesson is stark: Even hardened regimes change behavior when the money truly stops.

The outlier is Gaza, where the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) has operated since 1949. With about a $2 billion annual budget and 13,000 employees in Gaza alone, UNRWA functions as a quasi state, effectively providing medical services, education, and many other civil functions. Not only has it freed Hamas resources to focus on building its war machine, but Hamas has also taxed the incoming aid, commandeered it and sold it for profit, and placed its loyalists on UNRWA’s payroll—indeed, 49 percent of UNRWA employees in Gaza were Hamas members or their first-degree relatives. Donor states froze $450 million after revelations that UNRWA staffers and vehicles had participated in the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel—yet services resumed after several months, despite UNRWA’s refusal to introduce procedures to exclude Hamas from its ranks. Why did the donations resume? Lack of an alternative provider, said donor states—illustrating the trap long-running missions create.

Why the System Won’t Police Itself

Three forces make diversion durable. First is the moral override: When aid officials weigh “people will die tomorrow” against “fighters will grow stronger next month,” tomorrow understandably wins every time. Second is institutional survival: The humanitarian industry employs roughly 570,000 people worldwide and spends about $43 billion a year. Agencies that refuse the terms demanded by armed groups lose access, and organizations that lose access lose their budgets and staff. Third is adaptive and durable adversaries: Warlords do not rotate every couple of years the way aid workers do. They learn how to game the system, open front companies posing as nongovernmental organizations, and bill the UN for delivering its own cargo.

Add in a culture of secrecy—coding losses as “operational” for fear of donor backlash—and the result is an accountability inversion. Those who break the rules have the most leverage over those sworn to enforce them.

A Better Bargain Is Possible

Humanitarian aid is not doomed to fuel conflict. It does so because donors treat the four principles as scripture instead of tools. The central insight from Ethiopia’s recent pause and from earlier, shorter shutdowns in Yemen and Somalia is that money talks louder than moral persuasion. When funding truly dries up, even hard-line actors concede ground.

The United States, European countries, and the United Arab Emirates supply more than 70 percent of global humanitarian funding. Together, they could enforce five simple requirements on every grantee, public or private:

- Nondiversion benchmarks. All access fees, escorts, and local taxes must be disclosed up front. If a single benchmark is missed, funding pauses automatically for 12 months.

- Security integration. Grantees can either pay accredited guards vetted by donors or accept escorts from UN peacekeepers; covert deals with militias void the grant.

- Whistleblower insurance. 2 percent of every grant would fund external audits and legal defense for whistleblowers.

- Sunset clauses. Any mission that lasts longer than 10 years must shut down (allowing a one-year phase-out); exceptions require unanimous donor consent.

- Humanitarian innovation. Donor states should encourage and develop novel initiatives focused on the prevention of aid diversion, including better use of digitization and financial technology assets.

None of these measures requires rewriting international law. All rely on the single lever donors already control: money. Nor would tougher conditions necessarily doom civilians. During the Ethiopia pause, diversion dropped sharply while nutritional indicators remained flat—evidence that aid diversion operations had inflated caseloads far above real needs.

The Political Payoff

Reforming aid is not charity; it is strategy. Every dollar diverted to a rebel payroll or a palace slush fund is a dollar that undermines U.S. counterterrorism efforts, fuels migration pressures on Europe, and forces Gulf monarchies to spend double on military solutions. Conditional aid would flip those incentives. Regimes and armed groups that want the optics of international legitimacy would have to choose between guns and groceries, but not both.

Washington also gains a diplomatic dividend. Critics of U.S. foreign policy—from Beijing to Brasília—routinely accuse it of hypocrisy: demanding good governance while financing bad actors through humanitarian back doors. A transparent, conditional aid regime would undercut that narrative and restore credibility at a relatively low cost.

Facing Objections

Opponents argue that suspending aid is immoral because children will starve. This risk is real, but not definite. Aid stoppage in Ethiopia and Yemen, for example, did not result in a famine or a significant spike in malnutrition or mortality, indicating that much of the aid had never reached the most vulnerable populations to begin with. Rather, it was enriching the diverters with only marginal benefits for the truly needy.

In general, the worry about the consequences of aid stoppage has deterred dominant agencies from leaving the field so far—depriving the international community of the ability to judge the actual implications of stopping aid on the dynamics of exploitation and violence that become so intimately and cruelly intertwined with the aid.

Against the immediate risk of human suffering, one must also weigh the extension of that suffering for the long term. A survival analysis of 621 leaders in 123 countries from 1960 to 1999 shows that continued aid helps autocrats survive negative shocks because they can “stockpile” aid resources to buffer against crises, making them less vulnerable to domestic unrest or economic downturns. Cross-country evidence from the World Bank demonstrates that higher aid levels often correlate with lower bureaucratic quality, corruption, and weakened rule of law, especially in countries with weak domestic institutions. And where nondemocratic donors are influential, the chances of regime change plummet even further. While tightly targeted, accountable, and monitored aid could be less risky, this is currently not the norm. In most conflict zones, aid contributes to perpetuating authoritarianism and eroding long-term governance quality.

A second objection is legal: The principle of humanitarian neutrality forbids political conditions on aid. That reading mistakes principle for theology. Article 23 of the Fourth Geneva Convention requires the free passage of humanitarian consignments but allows belligerents to impose “necessary technical arrangements” and a “right of control.” Article 70 of the Additional Protocol I prohibits aid diversion. The conventions oblige aid providers to alleviate suffering wherever it occurs, yet they do not compel donors to bankroll the very fighters who cause that suffering. Conditionality that prevents diversion would better align humanitarian spending with humanitarian intent.

The Real Risk Is (to Continue) Doing Nothing

Over the next decade, climate shocks, urban sieges, and rising food prices will push aid needs past $50 billion a year. Without reform, much of that money will feed armies, not children. Worse, every scandal—oil-for-food in Iraq, stolen wheat in Ethiopia, kidnapped aid workers in Yemen—erodes public support in donor states, making future interventions politically toxic. The choice is stark: Tighten the taps now or watch the well run dry later.

Alex de Waal warned 20 years ago that “supplying food aid in on-going crises has a range of negative effects: it creates dependency, it paralyses agricultural systems, it increases the security risks faced by targeted populations, and it creates a war economy based on capturing these supplies.” De Waal was right, and the problem has only grown larger and more blatant in the intervening decades. The good news is that the fix is not technological, diplomatic, or military. It is managerial. Attach every truckload of rice to a clear, enforceable behavioral contract, and the balance of power flips overnight. Withholding aid is painful—but continuing to subsidize carnage is worse.

The world’s beleaguered civilians deserve more than sympathy. They deserve aid that stops feeding the guns trained on them. The United States and its allies can deliver that tomorrow—by refusing, at last, to pay for today’s wars.

– Netta Barak-Corren, Jonathan Boxman, Published courtesy of Lawfare.