The World Health Organisation and the United Nations have embarked on a campaign to vaccinate 4.7 million children against measles in Nigerian states affected by conflict. Chief Executive Officer of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control Chikwe Ihekweazu explains the importance of the massive campaign.

How prevalent is measles?

Measles is still one of the leading causes of death among young children in the world. In 1980, before widespread vaccination, measles caused an estimated 2.6 million deaths each year.

But the measles vaccine is considered one of the best buys in public health. Between 2000 and 2015 an estimated 20 million child deaths were prevented as a result of the vaccine being administered.

By 2015, about 85% of the world’s children were getting one dose of the measles vaccine by their first birthday. But still 134 200 children, mostly under the age of 5, died from measles that year. That’s about 367 deaths every day or 15 deaths every hour.

In Africa there has been an incredible reduction of the number of measles cases in the last five to 10 years. This is mainly as a result of intensive vaccination campaigns. But there are still a few problem areas.

Where are Africa’s hotspots and why have those countries not managed to crack the problem?

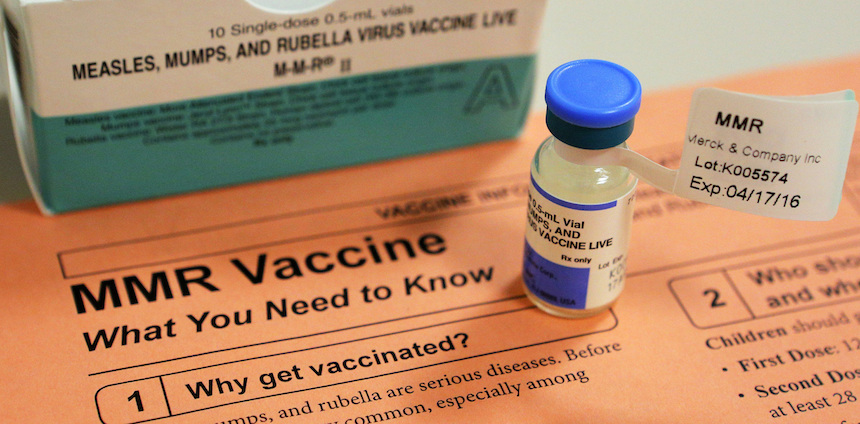

Nigeria is one. The Democratic Republic of Congo is another. The challenge is not the vaccine – it’s one of the oldest and cheapest around. It’s the way in which the vaccine needs to be transported. It is injectable and must be delivered through a supply chain process, or cold chain. For the vaccine to be effective it needs to be kept cold during transportation, storage and handling. But many primary health care centres and clinics don’t have electricity so the vaccine can’t be kept cold, and can’t be stored for any length of time.

The aim globally has been to eliminate measles. As part of this we launched two large measles vaccination campaigns in Nigeria over the past two years. This contributed to a significant reduction in the case load. But last year there were still cases being reported. This means that either the campaign was not as efficient as we thought it was or there was a problem with the cold chain. But there have been other contributing factors.

The first is malnutrition. Routine immunisation and vaccination campaigns in the North-Eastern parts of Nigeria have been particularly difficult due to the insurgency. These areas have been cut off from the rest of the country. One of the consequences is that children suffer from high levels of chronic under-nutrition.

Measles and malnutrition are a deadly combination. Once a child is malnourished and they contract measles, there is an increased chance that they will die.

Another challenge is the impact the insurgency has had on health care generally. Primary care infrastructure such as clinics have been affected significantly by the conflict. Thousands of people can’t access health centres as many have been destroyed.

This has disrupted vaccination activities which has increased the vulnerability of many children.

Why is Nigeria running a campaign to vaccinate four million children in the north-eastern part of the country?

The vaccination campaign was launched because it became possible to access areas previously out of reach. The conflict hasn’t stopped, but the government has made progress with the military to open up parts of conflict ridden areas. The vaccination campaign is one of several health initiatives that is being launched. There is also a feeding programme. The plan is to get this part of the country back up to speed.

What is unique about this campaign? And what are the logistics?

It’s unique because it’s the first time that a vaccination campaign has been run involving the military and health care workers. Doctors and nurses who are part of the army have been working with civilian health care workers.

The vaccination campaigns have been well attended so far. People in these areas have been coming out in their hundreds. Our analysis is that people view the injection as more potent than any other form of vaccination.

But logistics remains a challenge. Vaccination campaigns are hugely expensive and require the recruitment, training and mobilisation of thousands of health care workers.

In addition, the terrain is difficult. The areas we’re working in are very hot and dry. The fact that the vaccines need to be moved in cold boxes makes timing very important: when you leave and how you get it to the venues are the most problematic.

![]()

Chikwe Ihekweazu, Senior Honorary Lecturer on Infectious Diseases, UCL

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.