In recent weeks, California has experienced unusually heavy rainfall. California is also earthquake-prone, hosting the great San Andreas fault zone. If there is an unusual surge of earthquakes in the near future – allowing time for the rain to percolate deep into faults – California may well become an interesting laboratory to study possible connections between weather and earthquakes. The effect is likely to be subtle and will require sophisticated computer modeling and statistical analysis.

Earthquakes are triggered by a tiny additional increment of stress added to a fault already loaded almost to breaking point. Many natural processes can provide this tiny increment of stress, including the movement of plate tectonics, a melting icecap, and even human activities.

For example, injecting water into boreholes – either for waste disposal or to drive residual oil out of depleted reservoirs – is particularly likely to trigger earthquakes.

This is because water pressure in the fault zone is important in controlling when a geological fault slips. Fault zones invariably contain groundwater, and if the pressure of this water increases, the fault may become “unclamped.” The two sides are then free to slip past each other, causing an earthquake.

Hydrological changes do not need to be sudden or large to change the water pressure in a fault zone. As aquifers are depleted for irrigation, the water table slowly drops, which may also trigger earthquakes. It is thus unsurprising that extreme rainfall events might also encourage earthquakes. A number of instances of this have been flagged by scientists. For example, swarms of earthquakes in 2002 followed intense rainfall around Mt. Hochstaufen in Germany and the Muotatal and Riemenstalden regions of Switzerland.

Any study of the relationship between weather and earthquakes is likely to take time, and the results to be controversial. In the meantime, now is a good time to check that your gas heater is earthquake-secure and your emergency drinking water is fresh. After all, a “big one” could come at any time.

Triggering earthquakes

People knew we could induce earthquakes before we knew what they were. As soon as people started to dig minerals out of the ground, rockfalls and tunnel collapses must have become recognized hazards.

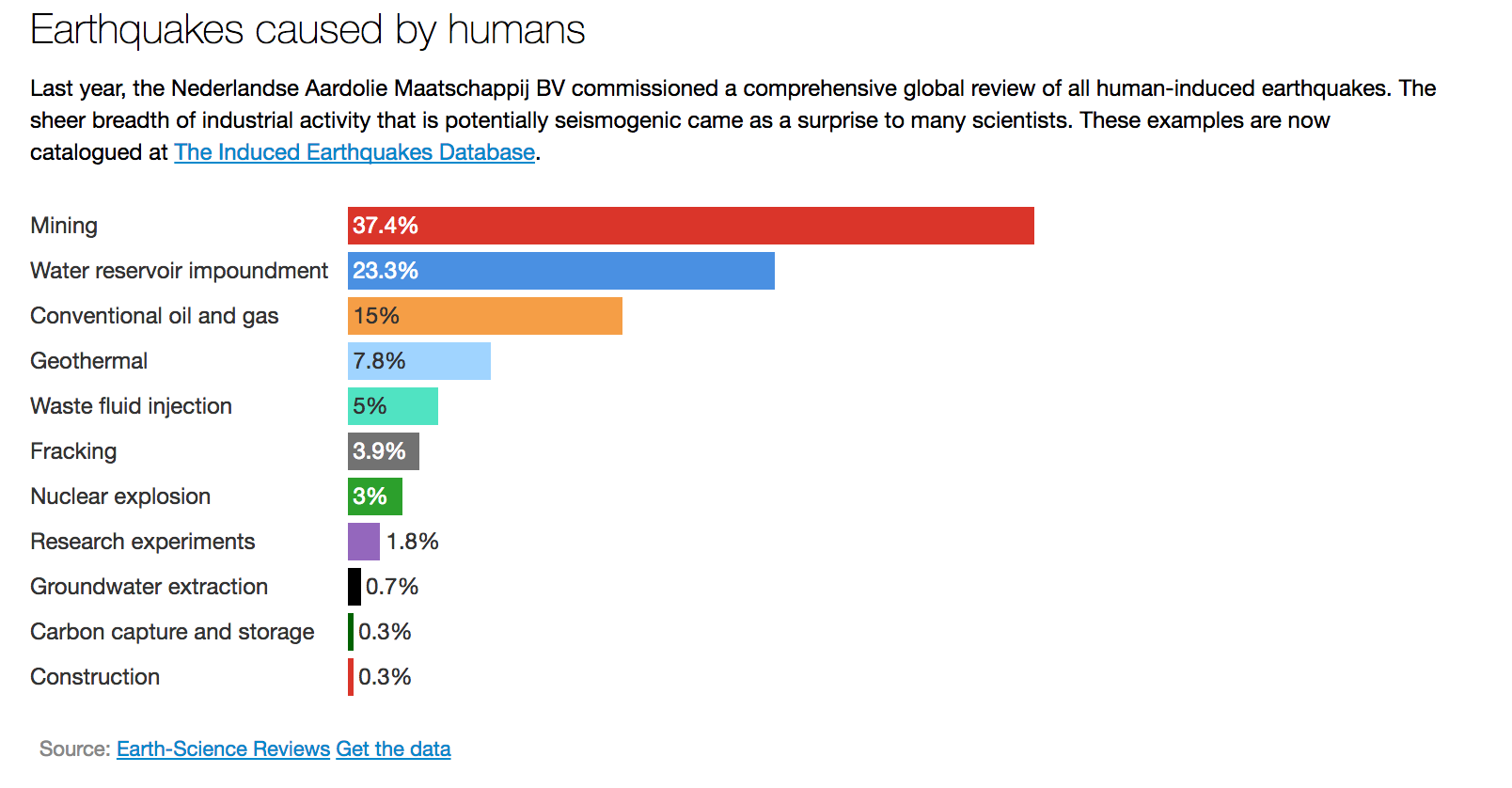

Today, earthquakes caused by humans occur on a much greater scale. Events over the last century have shown mining is just one of many industrial activities that can induce earthquakes large enough to cause significant damage and death. Filling of water reservoirs behind dams, extraction of oil and gas, and geothermal energy production are just a few of the modern industrial activities shown to induce earthquakes.

As more and more types of industrial activity were recognized to be potentially seismogenic, the Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij BV, an oil and gas company based in the Netherlands, commissioned us to conduct a comprehensive global review of all human-induced earthquakes.

Our work assembled a rich picture from the hundreds of jigsaw pieces scattered throughout the national and international scientific literature of many nations. The sheer breadth of industrial activity we found to be potentially seismogenic came as a surprise to many scientists. As the scale of industry grows, the problem of induced earthquakes is increasing also.

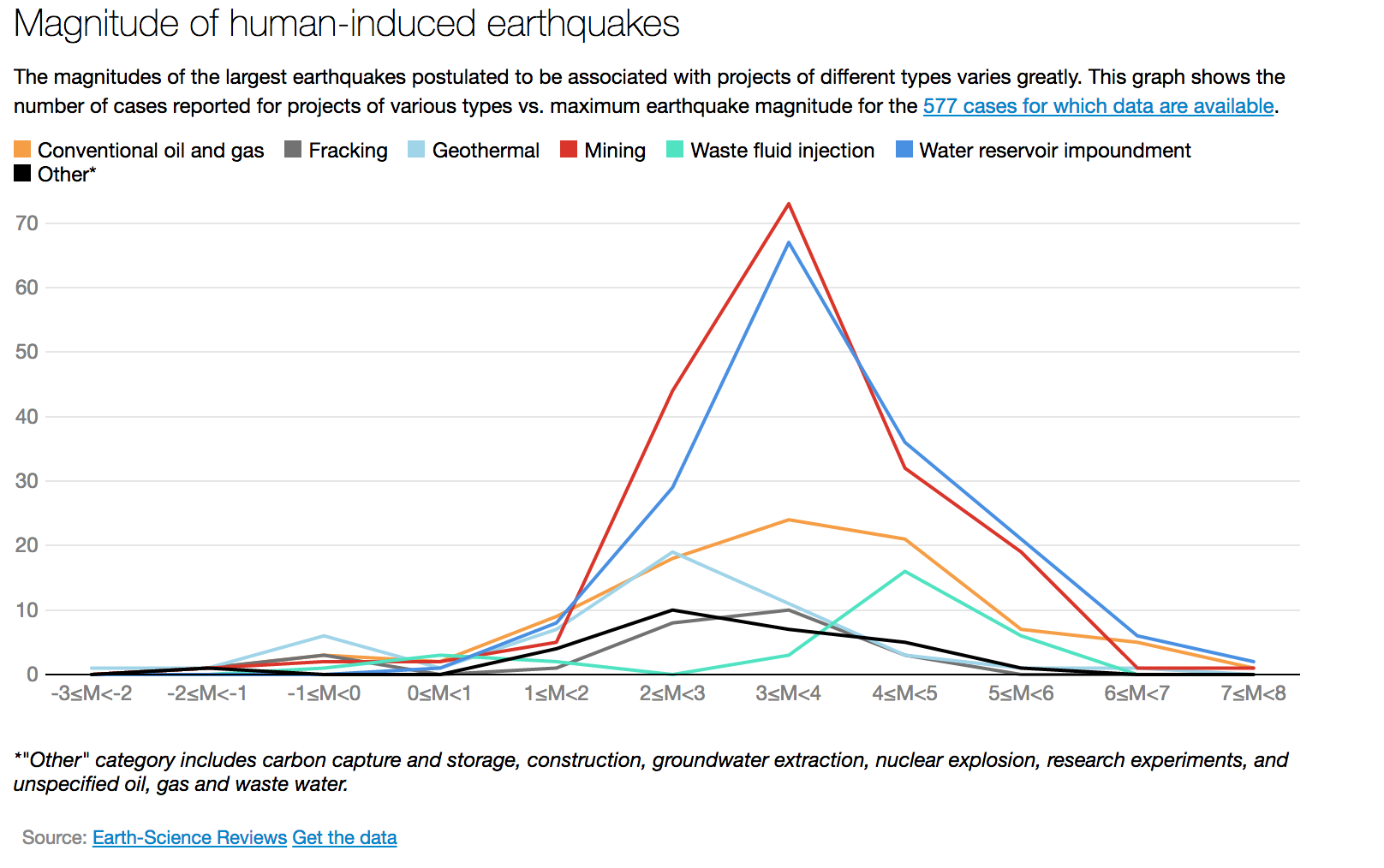

In addition, we found that, because small earthquakes can trigger larger ones, industrial activity has the potential, on rare occasions, to induce extremely large, damaging events.

How humans induce earthquakes

As part of our review we assembled a database of cases that is, to our knowledge, the fullest drawn up to date. In January, we released this database publicly. We hope it will inform citizens about the subject and stimulate scientific research into how to manage this very new challenge to human ingenuity.

Our survey showed mining-related activity accounts for the largest number of cases in our database.

Initially, mining technology was primitive. Mines were small and relatively shallow. Collapse events would have been minor – though this might have been little comfort to anyone caught in one.

But modern mines exist on a totally different scale. Precious minerals are extracted from mines that may be over two miles deep or extend several miles offshore under the oceans. The total amount of rock removed by mining worldwide now amounts to several tens of billions of tons per year. That’s double what it was 15 years ago – and it’s set to double again over the next 15. Meanwhile, much of the coal that fuels the world’s industry has already been exhausted from shallow layers, and mines must become bigger and deeper to satisfy demand.

As mines expand, mining-related earthquakes become bigger and more frequent. Damage and fatalities, too, scale up. Hundreds of deaths have occurred in coal and mineral mines over the last few decades as a result of earthquakes up to magnitude 6.1 that have been induced.

Other activities that might induce earthquakes include the erection of heavy superstructures. The 700-megaton Taipei 101 building, raised in Taiwan in the 1990s, was blamed for the increasing frequency and size of nearby earthquakes.

Since the early 20th century, it has been clear that filling large water reservoirs can induce potentially dangerous earthquakes. This came into tragic focus in 1967 when, just five years after the 32-mile-long Koyna reservoir in west India was filled, a magnitude 6.3 earthquake struck, killing at least 180 people and damaging the dam.

Throughout the following decades, ongoing cyclic earthquake activity accompanied rises and falls in the annual reservoir-level cycle. An earthquake larger than magnitude 5 occurs there on average every four years. Our report found that, to date, some 170 reservoirs the world over have reportedly induced earthquake activity.

![]()

The production of oil and gas was implicated in several destructive earthquakes in the magnitude 6 range in California. This industry is becoming increasingly seismogenic as oil and gas fields become depleted. In such fields, in addition to mass removal by production, fluids are also injected to flush out the last of the hydrocarbons and to dispose of the large quantities of salt water that accompany production in expiring fields.

A relatively new technology in oil and gas is shale-gas hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which by its very nature generates small earthquakes as the rock fractures. Occasionally, this can lead to a larger-magnitude earthquake if the injected fluids leak into a fault that is already stressed by geological processes.

The largest fracking-related earthquake that has so far been reported occurred in Canada, with a magnitude of 4.6. In Oklahoma, multiple processes are underway simultaneously, including oil and gas production, wastewater disposal and fracking. There, earthquakes as large as magnitude 5.7 have rattled skyscrapers that were erected long before such seismicity was expected. If such an earthquake is induced in Europe in the future, it could be felt in the capital cities of several nations.

Our research shows that production of geothermal steam and water has been associated with earthquakes up to magnitude 6.6 in the Cerro Prieto Field, Mexico. Geothermal energy is not renewable by natural processes on the timescale of a human lifetime, so water must be reinjected underground to ensure a continuous supply. This process appears to be even more seismogenic than production. There are numerous examples of earthquake swarms accompanying water injection into boreholes, such as at The Geysers, California.

Other materials pumped underground, including carbon dioxide and natural gas, also cause seismic activity. A recent project to store 25 percent of Spain’s natural gas requirements in an old, abandoned offshore oilfield resulted in the immediate onset of vigorous earthquake activity with events up to magnitude 4.3. The threat that this posed to public safety necessitated abandonment of this US$1.8 billion project.

What this means for the future

Nowadays, earthquakes induced by large industrial projects no longer meet with surprise or even denial. On the contrary, when an event occurs, the tendency may be to look for an industrial project to blame. In 2008, an earthquake in the magnitude 8 range struck Ngawa Prefecture, China, killing about 90,000 people, devastating over 100 towns, and collapsing houses, roads and bridges. Attention quickly turned to the nearby Zipingpu Dam, whose reservoir had been filled just a few months previously, although the link between the earthquake and the reservoir has yet to be proven.

The minimum amount of stress loading scientists think is needed to induce earthquakes is creeping steadily downward. The great Three Gorges Dam in China, which now impounds 10 cubic miles of water, has already been associated with earthquakes as large as magnitude 4.6 and is under careful surveillance.

Scientists are now presented with some exciting challenges. Earthquakes can produce a “butterfly effect”: Small changes can have a large impact. Thus, not only can a plethora of human activities load Earth’s crust with stress, but just tiny additions can become the last straw that breaks the camel’s back, precipitating great earthquakes that release the accumulated stress loaded onto geological faults by centuries of geological processes. Whether or when that stress would have been released naturally in an earthquake is a challenging question.

An earthquake in the magnitude 5 range releases as much energy as the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. A earthquake in the magnitude 7 range releases as much energy as the largest nuclear weapon ever tested, the Tsar Bomba test conducted by the Soviet Union in 1961. The risk of inducing such earthquakes is extremely small, but the consequences if it were to happen are extremely large. This poses a health and safety issue that may be unique in industry for the maximum size of disaster that could, in theory, occur. However, rare and devastating earthquakes are a fact of life on our dynamic planet, regardless of whether or not there is human activity.

Our work suggests that the only evidence-based way to limit the size of potential earthquakes may be to limit the scale of the projects themselves. In practice, this would mean smaller mines and reservoirs, less minerals, oil and gas extracted from fields, shallower boreholes and smaller volumes injected. A balance must be struck between the growing need for energy and resources and the level of risk that is acceptable in every individual project.

This article is an updated version of one published on Jan. 22, 2017.

Gillian Foulger, Professor of Geophysics, Durham University; Jon Gluyas, , Durham University, and Miles Wilson, Ph.D. Student in the Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.