This is the age of dissent – and the last decade saw a large rise in protest events across the UK. The relative social peace of the 1990s and 2000s has given way to a period of economic crisis and social conflict, sparked by the global economic crisis of 2008 and its aftermath.

Many viewed 2011 as the high point of this wave of protest – with occupations of public spaces taking place across the globe, not least during the Arab Spring. But the trend has, in fact, continued to proliferate throughout the decade. While austerity was the initial driver of protest in the UK, a wide range of issues are now leading to dissent.

My ongoing research project records UK protest events reported in the media since the 1980s. I last reported these results in 2015, highlighting how that year saw the highest number of reported protests during the period covered.

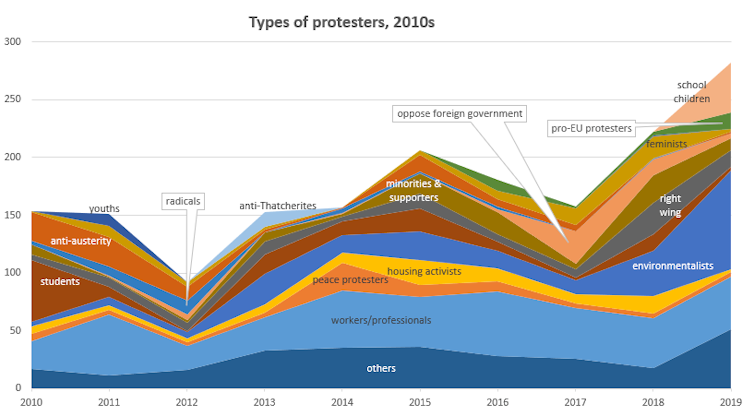

The end of the 2010s, however, now allows us to provide an overview of the changing nature of protest trends in Britain. As the figure below shows, reported protest events steadily rose throughout the decade. In 2019 there were over 280 reported protest events, compared with 154 in 2010 – and only 83 in 2007, the year before the global economic crisis hit.

The figure also allows us to identify the key groups who took part in protest activity during the 2010s. Workers and professionals – those whose protests related to the workplace – were the most consistent group protesting throughout the decade. These can be further broken down into types of workers/professionals (when that information is reported).

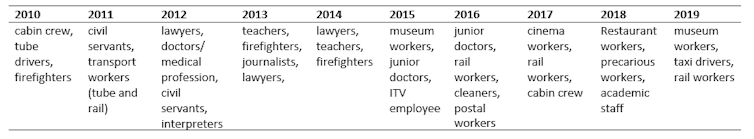

As the table below shows, this reveals a number of trends. Transport workers were especially prominent protestors throughout the period, including cabin crew, tube drivers, rail workers, and taxi drivers.

Also noteworthy are the professionals who (uncharacteristically) engaged in protest, including lawyers protesting cuts to legal aid, and junior doctors protesting changes to their contracts of employment.

Later in the decade, we also saw an increase in the number of precarious workers organising to protest their experience of low pay and job insecurity. These included cinema workers who mobilised to demand a living wage at Picturehouse Cinemas, restaurant workers in McDonalds and TGI Fridays, and a series of protest events organised specifically to challenge the precarious employment conditions of those working in service sector firms such as Wetherspoons, Uber Eats and Deliveroo.

Protest boom

The types of protesters who are most active and visible have also changed over the course of the decade. At the beginning the 2010s, the two main groups of protesters (alongside workers/professionals) were students protesting the increase of tuition fees, and anti-austerity activists protesting the coalition government’s imposition of a range of austerity measures, including cuts to welfare benefits, local government budgets, and an increase in regressive taxes such as VAT.

Throughout the decade, a number of other types of protester became more prominent, however, perhaps as a result of protest tactics becoming more commonplace and familiar, and as democracy has arguably become less open to popular input. In 2015, for example, there was an increase in the number of protests conducted by housing activists, including occupations of abandoned council housing by groups such as Focus E15, seeking to highlight the growing unaffordability of private housing, and the inaccessibility of social housing.

Those seeking to oppose the mistreatment of racialised minorities in the UK focused especially on the plight of immigrants and asylum seekers in detention centres, such as Yarls Wood, where more than 3,000 hunger strikes have been conducted by those held since 2015.

The Goldsmiths Anti-Racist Action (GARA) occupation of Deptford Town Hall in London lasted for 137 days in 2019, and successfully won a range of commitments by the university to tackle institutional racism. Unis Resist Border Controls has likewise highlighted the ongoing effects of the Hostile Environment within universities.

Many protests also sought to oppose the growing mobilisation of, and support for, far right groups and individuals such as Tommy Robinson, including the spate of “milkshake” protests which took place in 2019.

In 2017, there was also a large increase in opposition to foreign governments, particularly against US President Donald Trump and especially following his notorious “Muslim ban”.

Feminist protests also grew in prominence, mobilising around a range of issues. Sisters Uncut successfully organised a number of disruptive blockades, occupations and protests to highlight opposition to cuts to public services for domestic violence survivors. The Women’s March, which was organised to coincide with the inauguration of Trump, took place in cities across the country in 2017. And pro-choice feminists also successfully campaigned for the decriminalisation of abortion in Northern Ireland.

Deaths from domestic violence have reached a 5 year high with 173 being killed in 2018.

We are highlighting the impact of the Tory's cuts on domestic violence, as Parliament considers the DV bill next week. pic.twitter.com/RbfWxs1PSI— Leeds Sisters Uncut (@UncutLeeds) September 29, 2019

The demonstrations staged in support of the UK’s continued membership of the European Union saw a new wave of “self-admittedly middle-class” protestors.

But perhaps the most significant development in 2019 was the dramatic rise in the number of environmentalist protests – both those staged by Extinction Rebellion, and those conducted by school children. Together, these made up 45% of all reported protest events for the year.

Protest as progressive?

While protest is often considered to be the preserve of progressive causes, the rise of right-wing protesters towards the end of the decade perhaps challenges this view. Many of these protests were in support of Tommy Robinson following his arrest and imprisonment. Other protests sought to target refugees, staged by groups such as Britain First.

What is also notable, however, is the degree to which right-wing protesters were often far outnumbered by more progressive protesters – and counter-demonstrations were regularly held at the same time as far right protests. For instance, 2018 saw the largest wave of right-wing protest during the 2010s, boosted by a wave of anti-abortion demonstrations held outside abortion clinics. Even so, right-wing protests only represented 11% of all reported protest events for the year. On the whole, protest politics remains the preserve of progressive causes.

How to protest?

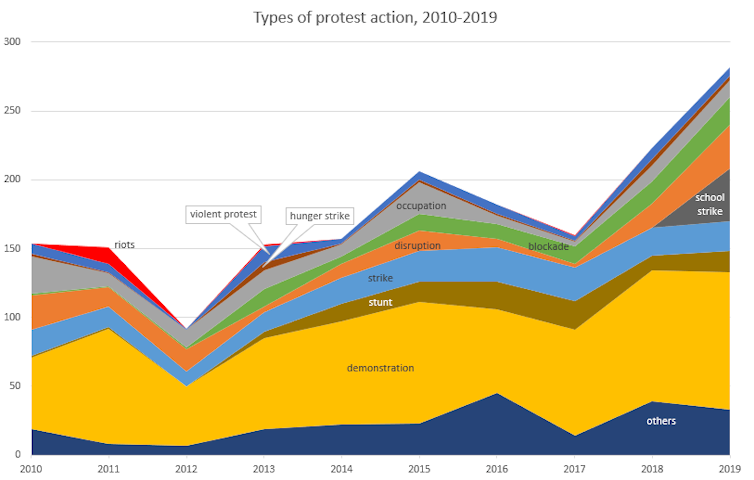

The dataset also records the types of protest activity conducted. As the figure below shows, demonstrations have consistently been the main type of protest activity throughout the decade. Demonstrations tend to have the effect of putting issues on the political agenda, while not necessarily causing considerable problems for authorities, as they tend to be legal and relatively undisruptive.

More confrontational forms of protest – including blockades, occupations, and disruptive protests – have also consistently been conducted throughout the decade, although they have tended to be less frequent than demonstrations. More violent or aggressive activities – such as the 2011 riots which followed the death of Mark Duggan – are relatively rare.

Hunger strikes were only rarely reported, which is surprising given that over 3,000 hunger strikes took place in UK immigration detention centres. Indeed, this highlights the media’s relative silence on the plight of those locked in the centres.

Something new

There are also ongoing efforts to identify innovative forms of protest. Cyclists staged a naked bike ride to highlight the lack of cycling provision; protesters opposing the burkini ban in France held a beach party outside the French embassy; Greenpeace activists put gas masks on key London statues to protest pollution; Save Our Hospital Services campaigners left a coffin outside the home of the (then) Conservative MP Sarah Wollaston; Extinction Rebellion activists stripped to their underwear in the House of Commons; and pro-EU protesters herded sheep down Whitehall to announce their opposition to Brexit.

#WearWhatYouWant protest in London best for kids and setting the bar high for the aesthetics of all future protests. pic.twitter.com/sKz9RLu1pi

— Caoimhe Mader McGuinness (@CaoimheMMC) August 25, 2016

The emergence of school strikes as a form of dissent in Britain also reflects both the rise of school children as agents of protest, and the influence of the global “Fridays for Future” movement, inspired by Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg’s campaign against climate change.

Birmingham climate strike pic.twitter.com/EnZYhwhMV3

— David Bailey (@djbailey231) September 20, 2019

What’s the point?

It is common to consider protests to be too blunt a means by which to influence public policy, and to dismiss the demands of protesters as insufficiently clearly articulated. Yet the impact of protest in terms of putting issues onto the political agenda is well documented. Protest also has a politicising effect upon individuals – many of those who were active in transforming the Labour Party as part of the Corbyn project also had considerable experience in protest politics.

While it is rare that those in power agree to all protest demands, it is much more common to see protests having an influence on the compromise that eventually results through the policymaking process.

The student protests against tuition fees resulted in the £21,000 income threshold, below which fees are not repaid (and which has since been raised to £25,000), considerably increasing the cost for the government. The government’s outgoing shale gas commissioner, meanwhile, lamented the influence of ongoing anti-fracking protests, such as the constant presence at Preston New Road, saying: “We are choosing to listen to a powerful environmental lobby campaigning against fracking rather than allowing science and evidence to guide our policy-making.” Fracking has since been banned, at least for now.

The 2010s have been a decade of austerity, acrimony, and growing frustration at a lack of democratic accountability. As we have seen, this has also been reflected in the rising trend of protest politics, as frustrations translate into growing attempts to find new and alternative ways to influence public policy.

While the Brexit debate may have ended (for now), hardship, inequality, and lack of democratic accountability remain key concerns – and high levels of protest are likely to continue. Indeed, the fact that school children have increasingly taken to protest suggests that the next generation will be further equipped to organise and conduct effective acts of dissent.

Politicians who refuse to listen to popular demands have a reason to be concerned. Watch this space.![]()

David J. Bailey, Senior Lecturer in Politics, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.