Government agencies and private security companies in the U.S. have found a cost-effective way to engage in warrantless surveillance of individuals, groups and places: a pay-for-access web tool called Fog Reveal.

The tool enables law enforcement officers to see “patterns of life” – where and when people work and live, with whom they associate and what places they visit. The tool’s maker, Fog Data Science, claims to have billions of data points from over 250 million U.S. mobile devices.

Fog Reveal came to light when the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a nonprofit that advocates for online civil liberties, was investigating location data brokers and uncovered the program through a Freedom of Information Act request. EFF’s investigation found that Fog Reveal enables law enforcement and private companies to identify and track people and monitor specific places and events, like rallies, protests, places of worship and health care clinics. The Associated Press found that nearly two dozen government agencies across the country have contracted with Fog Data Science to use the tool.

Government use of Fog Reveal highlights a problematic difference between data privacy law and electronic surveillance law in the U.S. It is a difference that creates a sort of loophole, permitting enormous quantities of personal data to be collected, aggregated and used in ways that are not transparent to most persons. That difference is far more important in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which revoked the constitutional right to an abortion. Dobbs puts the privacy of reproductive health information and related data points, including relevant location data, in significant jeopardy.

The trove of personal data Fog Data Science is selling, and government agencies are buying, exists because ever-advancing technologies in smart devices collect increasingly vast amounts of intimate data. Without meaningful choice or control on the user’s part, smart device and app makers collect, use and sell that data. It is a technological and legal dilemma that threatens individual privacy and liberty, and it is a problem I have worked on for years as a practicing lawyer, researcher and law professor.

Government surveillance

U.S. intelligence agencies have long used technology to engage in surveillance programs like PRISM, collecting data about individuals from tech companies like Google, particularly since 9/11 – ostensibly for national security reasons. These programs typically are authorized by and subject to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and the Patriot Act. While there is critical debate about the merits and abuses of these laws and programs, they operate under a modicum of court and congressional oversight.

Domestic law enforcement agencies also use technology for surveillance, but generally with greater restrictions. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable search and seizure, and federal electronic surveillance law require domestic law enforcement agencies to obtain a warrant before tracking someone’s location using a GPS device or cell site location information.

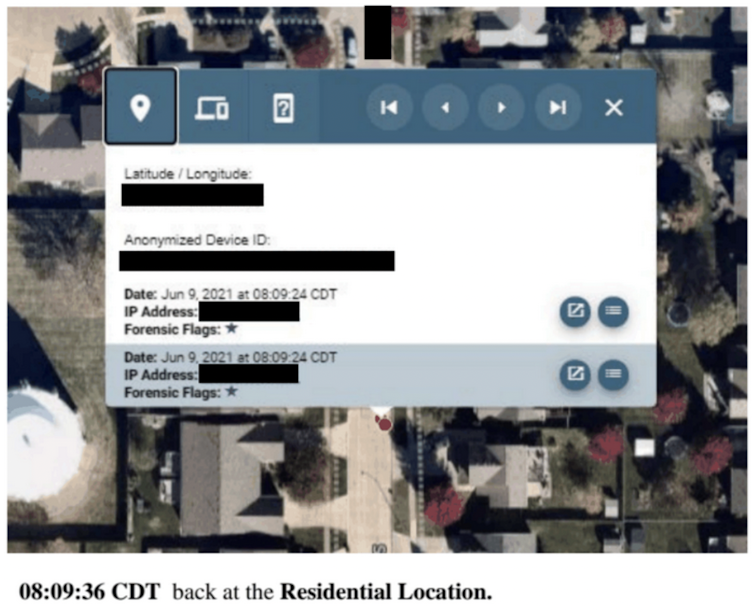

Fog Reveal is something else entirely. The tool – made possible by smart device technology and that difference between data privacy and electronic surveillance law protections – allows domestic law enforcement and private entities to buy access to compiled data about most U.S. mobile phones, including location data. It enables tracking and monitoring of people on a massive scale without court oversight or public transparency. The company has made few public comments, but details of its technology have come out through the referenced EFF and AP investigations.

Fog Reveal’s data

Every smartphone has an advertising ID – a series of numbers that uniquely identifies the device. Supposedly, advertising IDs are anonymous and not linked directly to the subscriber’s name. In reality, that may not be the case.

Private companies and apps harness smartphones’ GPS capabilities, which provide detailed location data, and advertising IDs, so that wherever a smartphone goes and any time a user downloads an app or visits a website, it creates a trail. Fog Data Science says it obtains this “commercially available data” from data brokers, permitting the tool to follow devices through their advertising IDs. While these numbers do not contain the name of the phone’s user, they can easily be traced to homes and workplaces to help police identify the user and establish pattern-of-life analyses.

Law enforcement use of Fog Reveal puts a spotlight on that loophole between U.S. data privacy law and electronic surveillance law. The hole is so large that – despite Supreme Court rulings requiring a warrant for law enforcement to use GPS and cell site data to track persons – it is not clear whether law enforcement use of Fog Reveal is unlawful.

Electronic surveillance vs. data privacy

Electronic surveillance law protections and data privacy mean two very different things in the U.S. There are robust federal electronic surveillance laws governing domestic surveillance. The Electronic Communications Privacy Act regulates when and how domestic law enforcement and private entities can “wiretap,” i.e., intercept a person’s communications, or track a person’s location.

Coupled with Fourth Amendment protections, ECPA generally requires law enforcement agencies to get a warrant based on probable cause to intercept someone’s communications or track someone’s location using GPS and cell site location information. Also, ECPA permits an officer to get a warrant only when the officer is investigating certain crimes, so the law limits its own authority to permit surveillance of only serious crimes. Violation of ECPA is a crime.

The vast majority of states have laws that mirror ECPA, although some states, like Maryland, afford citizens more protections from unwanted surveillance.

The Fog Reveal tool raises enormous privacy and civil liberties concerns, yet what it is selling – the ability to track most persons at all times – may be permissible because the U.S. lacks a comprehensive federal data privacy law. ECPA permits interceptions and electronic surveillance when a person consents to that surveillance.

With little in the way of federal data privacy laws, once someone clicks “I agree” on a pop-up box, there are few limitations on private entities’ collection, use and aggregation of user data, including location data. This is the loophole between data privacy and electronic surveillance law protections, and it creates the framework that underpins the massive U.S. data sharing market.

The need for data privacy law

Without robust federal data privacy safeguards, smart device manufacturers, app makers and data brokers will continue, unfettered, to utilize smart devices’ sophisticated sensing technologies and GPS capabilities to collect and commercially aggregate vast quantities of intimate and revealing data. As it stands, that data trove may not be protected from law enforcement agencies. But the permitted commercial use of advertising IDs to track devices and users without meaningful notice and consent could change if the American Data Privacy Protection Act, approved by the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce by a vote of 53-2 on July 20, 2022, passes.

ADPPA’s future is uncertain. The app industry is strongly resisting any curtailment of its data collection practices, and some states are resisting ADPPA’s federal preemption provision, which could minimize the protections afforded via state data privacy laws. For example, Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, has said lawmakers will need to address concerns from California that the bill overrides the state’s stronger protections before she will call for a vote on ADPPA.

The stakes are high. Recent law enforcement investigations highlight the real-world consequences that flow from the lack of robust data privacy protection. Given the Dobbs ruling, these situations will proliferate absent congressional action.![]()

Anne Toomey McKenna, Visiting Professor of Law, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.