Looking at all the full spread of last week’s activity reveals a broad, interagency effort to counter Russian influence operations.

In November 2023, a new media company offering video content from “fearless voices” opened its doors. “Uncensored, Unapologetic, Unafraid,” read Tenet Media’s slogan under a launch video featuring footage of the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol intercut with dramatic black-and-white shots of the right-wing influencers hired to join the network. “The challenge for all of us,” said one of the influencers, Dave Rubin, “is to not be passive participants in letting the country slip away.”

There was just one problem. According to the Justice Department, Tenet Media was—unbeknownst to the influencers—a front for the Kremlin-controlled Russian media company RT.

On Sept. 4, the Justice Department unveiled an indictment against the two RT employees allegedly running this scheme, charging them with conspiracy to violate the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) and evade U.S. sanctions on Russia through money laundering. Especially when reviewed alongside some of the videos posted on the Tenet Media YouTube channel, the indictment makes for a bizarre read—chronicling how RT allegedly paid prominent YouTube personalities hundreds of thousands of dollars to produce videos “often consistent with the Government of Russia’s interest in amplifying U.S. domestic divisions.”

But that indictment was only one piece of a much larger U.S. government effort. Alongside these charges, the Justice Department also announced the seizure of 32 web domains used by actors linked to the Russian government to spread propaganda. The Treasury Department declared new sanctions against figures linked to that propaganda campaign, along with RT employees and leaders (including the two the Justice Department just indicted) and figures involved with a “pro-Kremlin hacktivist group.” The State Department took action as well, including by offering a $10 million reward for information on organizations attempting to influence or interfere in U.S. elections. The very next day, the Justice Department announced two more indictments targeted at Russia: one against a TV presenter working with a sanctioned Russian television channel, along with the man’s wife, and another against a GRU hacking group for cyberattacks on Ukraine.

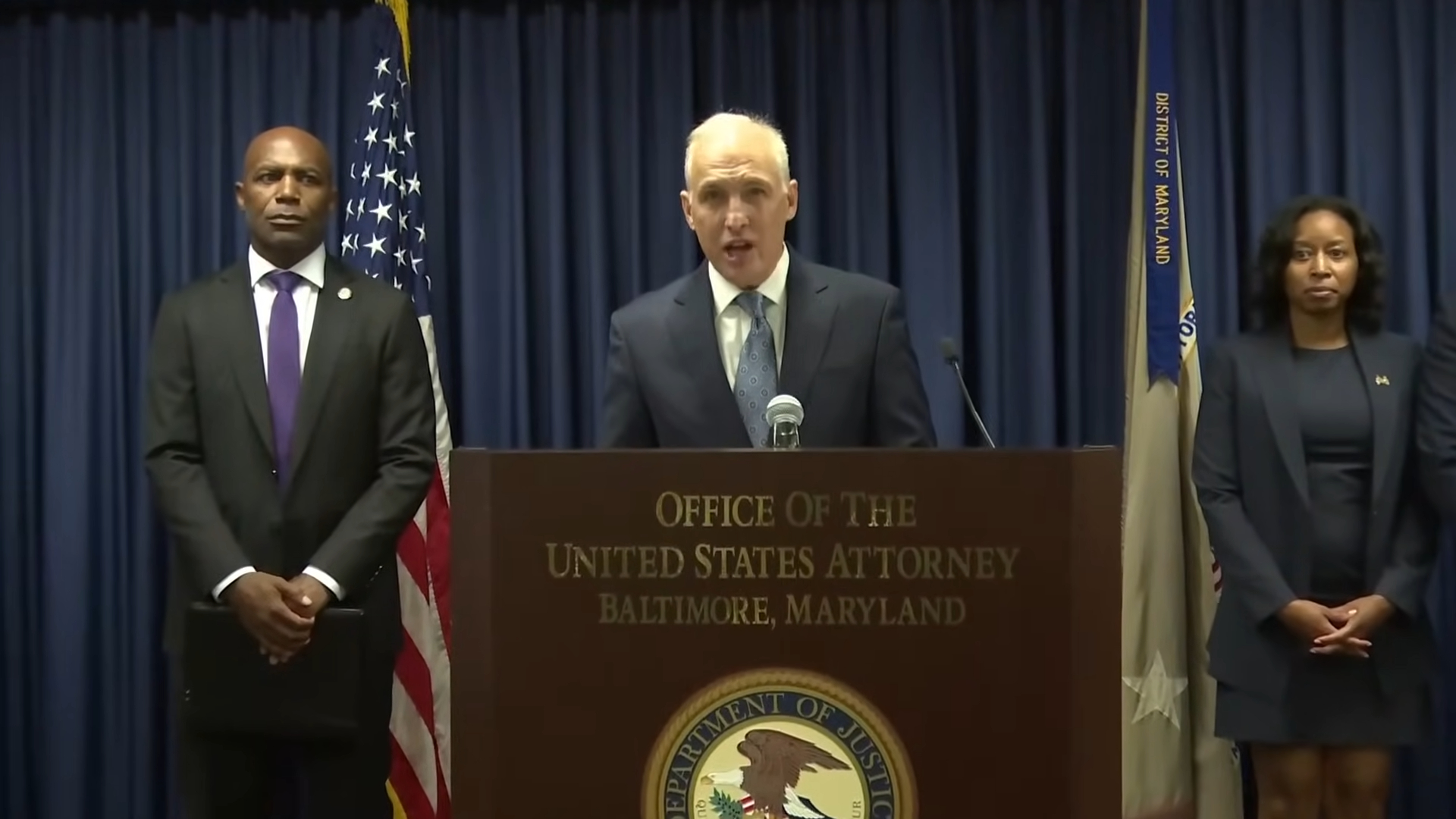

Last week was, in other words, a very busy week at the Justice Department and across other agencies when it comes to U.S. policy toward Russia. “We will be relentlessly aggressive in countering attempts to interfere in our elections and undermine our democracy,” Attorney General Merrick Garland told reporters.

So far, the bulk of news coverage has focused on examining these different actions piecemeal—and, to be fair, there’s a lot to dig in to. But taking a look at the full spread of last week’s activity helps reveal the broad scope of the U.S. government effort across multiple agencies, responding to Russian efforts aimed at undermining both the U.S. and Ukraine. These actions pull together a number of different threads concerning the U.S. response to foreign interference and Russian activities in Ukraine—particularly in contrast to how the government handled a similar Russian campaign in 2016. The U.S. strategy has departed from eight years ago in two significant ways: It’s holding specific individuals and entities accountable in near-real time, and it’s aggressively identifying and communicating Russian operations to the public.

What’s in the Documents?

The RT indictment has so far received the most attention among the commentariat—likely because the influencers allegedly duped by RT appear to be prominent names in the online right-wing media sphere. The indictment doesn’t mention Tenet Media by name, but press reports have identified the company as matching the details included in the charging document. The influencers affiliated with Tenet include Tim Pool, Benny Johnson, and Dave Rubin—all of whom have posted statements to Twitter disclaiming any knowledge of Russian influence. Two days after the charges became public, another Tenet contributor announced that “TENET Media has ended after the DOJ indictment.”

According to the indictment, the two RT employees, Konstantin Kalashnikov and Elena Afanasyeva, used fraudulent personas to work with two individuals in the United States—identified only as Founder-1 and Founder-2, but identified by the press as Canadian right-wing YouTuber Lauren Chen and her husband Liam Donovan—to set up a new media company ostensibly funded by a nonexistent beneficiary named “Eduard Grigoriann.” The founders appear to have had some sense of just who their beneficiaries actually were: The indictment describes the founders referring at various points to “the russians” and googling “time in Moscow” while awaiting a response from Kalashnikov and Afanasyeva’s personas on the company’s Discord channel. They recruited a number of media personalities at exorbitant rates: “Commentator-1” received a monthly fee of $400,000 and a signing bonus of $100,000, while “Commentator-2”—who, from details included in the indictment, appears likely to be Pool—received $100,000 per YouTube video.

As time went on, Kalashnikov and Afanasyeva seem to have become more aggressive about pushing the Kremlin line, encouraging Tenet to blame Ukraine for a March 2023 terrorist attack on Moscow for which ISIS claimed credit, and at another point demanding that Tenet promote a video of “a well-known U.S. political commentator”—seemingly Tucker Carlson—“visiting a grocery store in Russia.” (Posting the Carlson video “just feels like overt shilling,” a Tenet employee allegedly complained.)

But, according to the Justice Department, this was far from the only influence operation linked to Russia. The department also released an affidavit in support of its seizures of a number of domains used “to covertly spread Russian government propaganda with the aim of reducing international support for Ukraine, bolstering pro-Russian policies and interests, and influencing voters in U.S. and foreign elections.” The group behind the domains, “Doppelganger,” is a familiar player: In March 2024, the Treasury Department sanctioned the Moscow-based company behind the group, along with the company’s Russian founder, for running a “persistent foreign malign influence campaign at the direction of the Russian Presidential Administration.”

Doppelganger was first identified in 2022 by researchers at the EU DisinfoLab, who showed how the organization published fake news stories on websites fashioned to fool viewers into believing they were reading a real article from a familiar and trusted outlet. The group—which the affidavit states bluntly is “under the direction and control of the Russian government”—appears to have used the same technique here, publishing fake articles sourced to the Washington Post, Fox News, and other U.S. outlets. The substance of the articles varies: Some attack Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and seek to undermine U.S. support for Ukraine; others complain about the U.S. national debt or boost claims of potential U.S. civil war.

There’s more. The same day the Justice Department announced its indictments, the Treasury and State departments announced their own actions to combat Russian influence. Treasury designated 10 individuals and two entities pursuant to Executive Order 14024, which aims to disrupt “specified harmful foreign activities of the Government of the Russian Federation,” including its efforts to undermine democratic institutions. The Treasury Department pointed to much of the same kind of conduct described in the Justice Department’s indictment—in particular, RT’s covert recruitment of American influencers—but took action against a wider group. Alongside Kalashnikov and Afanasyeva, Treasury sanctioned RT’s editor-in-chief and three other high-level RT employees. Treasury also took action against three members of a pro-Kremlin hacktivist group called RaHDit. The announcement says very little about RaHDit’s connection to the overarching goal of coordinating actions to combat Russian election interference, however; instead, it merely describes the group’s creation of “cyber tools,” including those used by the FSB. The two entities and the final individual targeted by Treasury’s action were a nonprofit organization called Autonomous Non-Profit Organization (ANO) Dialog, ANO Dialog’s director, and ANO Dialog’s subsidiary ANO Dialog Regions.

Meanwhile, the State Department announced that it was taking three actions to “hinder malicious actors from using Kremlin-supported media as a cover to conduct covert influence activities.” First, the department imposed new visa issuance restrictions against individuals associated with those media organizations; in accordance with confidentiality requirements, it did not disclose exactly to whom the restrictions will apply. The department also exercised its authority under the Foreign Missions Act to designate as foreign missions a Russian media organization, Rossiya Segodnya, and three of its subsidiaries. As a result, each organization is now required to inform the State Department of all personnel working in the United States, as well as all real property located here. Finally, the department announced that its Diplomatic Security Service will award up to $10 million to anyone who provides information on “potential foreign efforts to influence or interfere in U.S. elections.” It specifically identified RaHDit—the hacktivist group whose members have been simultaneously sanctioned by Treasury—as an organization of interest, pointing to its history of election influence, its association with Russian intelligence and security services, and its cyber-enabled dissemination of RT propaganda and disinformation.

All this happened on Sept. 4. But the Justice Department, apparently, was not done. Just a day later, the department announced indictments of Dimitri Simes, a longtime Washington, D.C., fixture and the former president and CEO of the Center for the National Interest, and Simes’s wife—alleging that Anastasia Simes worked to violate U.S. sanctions on Russia by purchasing art in the U.S. on behalf of a sanctioned Russian oligarch, and that her husband likewise sought to evade sanctions in his role as a commentator on the Russian state-controlled television station Channel One. According to the indictment, Simes continued to work with Channel One even after the Treasury Department sanctioned the station for its links to the Russian government following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. To work around sanctions, the channel allegedly deposited money into Simes’s U.S. bank account by using an Armenian bank as an intermediary.

And then, just to make the flurry of indictments even more dizzying, the Justice Department also released an indictment of six Russian hackers—five of them members of the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency—for hacking into Ukrainian government systems in 2022. The U.S. government had previously attributed those malicious cyber operations to Russia shortly after they took place—but now prosecutors are adding five defendants and tacking on an additional money laundering charge against the original defendant.

“We’re seeing more and more” attempts at election interference, Garland told reporters on Sept. 4. “It’s coming faster and faster.” What might the trove of information released by the U.S. government suggest about what these Russian attempts will continue to look like from now until the election?

What Is Russia Up to?

So far, much of the commentary around these indictments and related actions has focused on Russia’s tactics and strategy—what the Kremlin is up to and how its approach to election interference has changed from previous years. A review of the RT indictment and the Doppelganger affidavit reveals plenty of commonalities with Russian active measures in the past, most notably 2016. The goal is generally to stir up chaos and amplify social divisions, but there’s a preference for boosting the fortunes of one political party over the other. One translated planning document included in the Doppelganger affidavit states, “It makes sense for Russia to put a maximum effort to ensure that the [U.S. Political Party A] point of view (first and foremost, the opinions of [Candidate A] supporters) wins over the US public opinion.” From context, this is clearly referring to Trump and the Republican Party. Elsewhere in the document, the planners state that their “Goals and Objectives” include “to secure victory of a [U.S. Political Party A] candidate … at the U.S. presidential elections to be held in November of 2024.”

Russia seems to be especially focused on shaping U.S. opinion around Ukraine. Recall the push by the RT employees to have Tenet blame Ukraine for the 2024 terrorist attack—an obviously absurd line of propaganda pushed by the Russian government at the time. Likewise, Doppelganger’s work as described in the affidavit focused repeatedly on driving down Americans’ support for U.S. backing of Ukraine. It’s worth recalling that Ukraine also featured heavily in Russia’s 2016 election interference, as well: The Mueller report describes how a likely GRU operative tried to sell the 2016 Trump campaign on a “peace plan” to resolve the conflict between Russia and Ukraine as it stood then, which would have involved ceding large swathes of territory in eastern Ukraine to Russia.

During the 2016 campaign, Russia’s influence campaign took two main forms: first, a program by the Internet Research Agency (IRA, run by oligarch-cum-warlord Yevgeny Prigozhin, now sadly incinerated) to make incendiary political posts on social media under fake American identities; and second, a GRU-run hack-and-leak campaign that publicly distributed damaging internal Democratic Party documents via WikiLeaks. At the tech publication Platformer, Casey Newton suggests that the Doppelganger and RT projects of 2024 may reflect a new need to work around guardrails set up by social media platforms in response to the IRA’s campaign in 2016. It’s no longer quite so easy to run a large network of inauthentic accounts without anyone noticing. Instead, Newton points out, Russia has adapted to these changing circumstances:

Doppelganger deemphasizes direct sharing on platforms in favor of creating lookalike websites that can be linked to on social networks without raising suspicions at the platform level. And the RT project avoids the hassle of creating a fake account with a large following by funneling money to unwitting sympathizers to the cause.

As Renee DiResta wrote on Threads, “Buying authentic influencers is a far better use of funds than creating fake personas, because they bring their own trusting audiences and are actually, you know, real.” This tactic of quietly funding ideological allies—potentially without those allies’ knowledge—dates back to the Cold War. More recently, China has previously funded influencers from outside the country in order to enhance its international reputation.

Increased sophistication on the part of platforms, and increased collaboration between platforms and the U.S. government, necessitated more stealth. But so too did the broad swathe of sanctions levied on Russian entities following the invasion of Ukraine. During the 2016 election, RT was busy pumping out English-language propaganda for U.S. audiences under its own name. Under pressure, it registered as a foreign agent in 2017—hence the Justice Department’s decision to charge Kalashnikov and Afanasyeva with conspiracy to violate FARA by pushing RT content through a company that itself hadn’t registered as a foreign agent. But RT’s operations have since been severely limited. As the indictment states, “After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, RT was sanctioned, dropped by distributors, and ultimately forced to cease formal operations in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the European Union.” Instead, RT appears to have shifted toward pushing its message covertly through other mouthpieces.

If these first two charging documents—and the associated actions from the State and Treasury departments—speak directly to alleged Russian efforts to interfere in the 2024 election, the subsequent indictments of the Simeses and the GRU-linked hackers are less obviously connected. The hacking indictment provides greater detail about the specific officers responsible for the 2022 incident in Ukraine and the GRU unit to which they belong: the notorious Unit 29155, which has been linked to a number of assassination attempts, including the 2018 poisoning of Sergei Skripal. In addition to the indictment announced by the Justice Department, the FBI, the National Security Agency, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency—in conjunction with a group of countries including the U.K., Australia, and Ukraine—released an advisory on Unit 29155’s hacking activities. The group’s objectives “appear to include the collection of information for espionage purposes, reputational harm caused by the theft and leakage of sensitive information, and systematic sabotage caused by the destruction of data,” the announcement states.

In Simes’s case, the issue is a seemingly blatant case of sanctions evasion—a glimpse of how Russia’s elite has attempted to work around the aggressive sanctions implemented after the invasion of Ukraine. But the indictment of Dimitri Simes also provides a tantalizing glimpse inside the workings of Russian state television. Simes is a panelist on the Channel One show “The Great Game,” which purports to provide both a Russian and an American perspective on geopolitics; Simes, ironically, is meant to represent the American perspective. The indictment describes conversations between Simes and the Kremlin, including with Vladimir Putin himself, sometimes including directions on how to cover specific issues related to the war in Ukraine. Over the course of 2023, Simes allegedly worked with the Kremlin to develop a nominally independent project meant to promote “actions which would convince America not to commit hostile acts against Russia,” in Simes’s description, and which would “unequivocally support the Russian president’s direction in foreign policy and state security.” It’s not clear if any of this material became public.

What Is the U.S. Up to?

As Garland said last week, Russian efforts to interfere in the 2024 election will likely only increase in the lead-up to the election. The same might be true of the U.S. government’s public efforts to counter such influence. If the Russian government has changed its strategy since 2016, so too has the U.S. government. During that campaign season, the intelligence community released only a single, relatively terse statement about Russia’s effort to meddle in the election—months after hacked Democratic Party emails first surfaced. It was only after the beginning of congressional investigations and the Mueller probe that the public first learned many of the details of Russian interference.

This time around, in contrast, the government seems to have decided on an approach of sharing as much information as possible—hence the blizzard of information coming out of the Justice Department last week. (The FBI reflected a similar commitment to transparency in its rapid acknowledgement of an ongoing investigation into Iranian hacking of the Trump campaign—a separate thread of foreign interference this election.) Read together, the court filings provide an extraordinary amount of information about Russian activities in the U.S. and Ukraine. The Doppelganger affidavit, in particular, includes almost 200 pages of internal planning documents and English translations. This isn’t just a public awareness campaign, but an effort to show the intelligence community’s work. You don’t have to trust what the U.S. government is saying—you can look at the primary source documents yourself.

The simultaneous efforts by multiple agencies—Justice, Treasury, and State—are also worth noting. This is a coordinated effort across the government as a whole. In announcing these actions, each agency deployed its own legal authorities in a common effort to combat what they variously described as “[Russia’s attempts] to exploit our country’s free exchange of ideas in order to covertly further its own propaganda efforts” (Justice), “activities that aim to deteriorate public trust in our institutions” (Treasury), and “covert influence activities that target the U.S. elections in 2024 and undermine our democratic institutions” (State).

Notably, all three agencies emphasized that their targeting of Russian media and influence efforts had nothing to do with the content of those efforts—undoubtedly a preemptive retort to inevitable accusations of political bias. Speaking at an event convened by the Aspen Institute on Sept. 4, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco emphasized that the Justice Department’s actions reflected a focus on the foreign actors themselves but was “agnostic as to particular messaging.” Recall, too, how the Doppelganger affidavit redacted the names of political parties and candidates in its recitation of facts, though the Russian preference for Trump was clear from context. The State Department announcement likewise explained that it was “taking these actions against these individuals exclusively for their nefarious, covert influence activities, and not for the content of any reporting or disinformation activities.”

All of them, of course, were focused on the particular threat coming from Russia, notwithstanding recent disclosures about other countries’ efforts to interfere in U.S. elections. But it’s clear that the departments agreed that it was important to make a show of force against Russia in particular. (Though it’s worth noting that the three agencies took similar coordinated action with respect to Chinese hackers earlier this year.)

How, then, do the GRU and Simes indictments fit into this picture? They are not, on the surface, directly related to one another in the same way that the Doppelganger and RT actions were. Nor do they obviously fit with the theme of countering election interference. One possibility is that the flurry of activity last week was designed as a show of force against Russia on multiple fronts—not just on the matter of election interference, but in terms of its actions in Ukraine and its efforts to evade wartime sanctions as well. Perhaps it was a happy coincidence that the GRU and Simes indictments were ready to go immediately after the Sept. 4 blitz.

But there’s telling overlap between the two sets of cases. For one thing, Dimitri Simes is a familiar player when it comes to Russian election interference. Eagle-eyed readers will recall that he appeared in the Mueller report as a possible vector of Kremlin outreach to the 2016 Trump campaign, though he was never charged. Simes was also linked to Maria Butina, a Russian activist who pleaded guilty in 2018 to FARA charges for acting as an unregistered Russian agent working to infiltrate the American right. Butina is now a member of the Russian Duma; she has expressed her support for the war in Ukraine and was sanctioned in 2022 by the Treasury Department after Russia’s invasion.

The war in Ukraine, clearly, is a common theme across these U.S. actions. It’s the cause of the sanctions that Simes and his wife allegedly evaded; the subject of the GRU hacking operation; and, throughout the Simes indictment, the RT indictment, and the Doppelganger affidavit, the subject of dogged Kremlin efforts to shape American public perception. Similarly, the Treasury and State department actions announced alongside the Justice Department’s election interference news blitz included information on the pro-Kremlin hacktivist group RaHDit, which appeared after the invasion of Ukraine and specializes in doxing people allegedly working with the Ukrainian military. Treasury sanctioned three individuals affiliated with RaHDit on the basis of their work with Russian intelligence and their role developing apparently nefarious cyber tools, including RaHDit’s director, FSB officer Aleksey Garashchenko. And the State Department specifically identified both RaHDit and Garashchenko when describing the kind of information for which it would grant its up-to-$10 million reward.

On its page detailing the $10 million award, the department focuses on RaHDit’s hack-and-leak initiatives targeting Ukrainians and their supporters. This would seem to put the actions against RaHDit in the same category as the GRU indictment: U.S. government response to Russian cyber activity against Ukraine. But in the Sept. 4 press release, the State Department also points to RaHDit’s history of interfering in foreign elections using “cyber-enabled influence operations”—and emphasizes that RaHDit “is a threat to the 2024 U.S. elections.” Perhaps, then, last week’s slate of actions should be understood as a unified U.S. push to defend both U.S. democracy and democracy in Ukraine.

Speaking to reporters about the GRU indictment on Sept. 4, Assistant Attorney General for National Security Matt Olsen said, “The message is clear to the G.R.U. and to the Russians. We are on to you; we have penetrated your systems.” This could also be read as a warning against future efforts at election interference as well: if you try anything—like a hack-and-leak, for example—we’ll find out, and we’ll warn the American people you’re targeting with these operations.

This overview has only scratched the surface of all the questions raised by last week’s events. Why, for example, are Founder-1 and Founder-2 not charged in the RT indictment, despite the allegation that they were aware they were acting on behalf of the Russian government? What does it say that the American right has become sufficiently aligned with the Kremlin line on a variety of issues that influencers were a ripe target for Russian funding? Did any of this propaganda have a measurable effect on American public opinion, or was the Kremlin just wasting money? For that matter, will the government’s effort to inform Americans about this influence operation have any effect, or have polarization and a splintered media environment made it impossible for this news to break through? And how does all this fit into the bigger picture of foreign influence in the 2024 election—not just from Russia, but from Iran, China, and potentially others as well?

With two months to go until the election, the U.S. government is working to make sure that 2024 is not a repeat of 2016. What other announcements might the government make in the run-up to November?

– Quinta Jurecic, Natalie K. Orpett, Published courtesy of Lawfare.