Rains in northern California have helped firefighters contain the Camp Fire, which now ranks as the state’s most deadly wildfire. But unfortunately, all signs point to worsening events ahead in the North American West. Critically, the risk extends well beyond California, and better forest management alone won’t solve the problem.

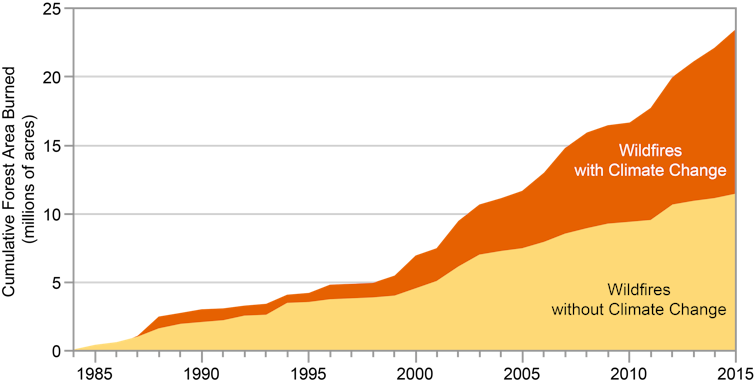

There are multiple reasons why wildfires are getting more severe and destructive, but climate change tops the list, notwithstanding claims to the contrary by President Donald Trump and Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke. According to the latest U.S. National Climate Assessment, released on Nov. 23, higher temperatures and earlier snowmelt are extending the fire season in western states. By 2050, according to the report, the area that burns yearly in the West could be two to six times larger than today.

For climate scientists like me, there’s no longer any serious doubt that human activity – primarily burning fossil fuels – is causing the atmosphere to warm relentlessly.

Climate change is driving a rapid increase in wildfire risk that has become a national problem. At the same time, healthy forests have become essential for the many valuable benefits they provide the nation and its people. Neither more effective forest management, nor curbing climate change alone will solve the growing wildfire problem, but together they can.

The threat of climate-driven wildfires

Increasing wildfire risk is already the reality for much of the western United States, particularly in California, the Pacific Northwest, the mountains of the desert Southwest and the Southern Rockies, where warmer temperatures and drier conditions are major contributors. As the climate continues to warm, elevated risks of forest stress and die-off, vegetation transformation and wildfire will spread across the United States. Moreover, the problem is global.

Studies have shown that climate change increases the frequency, duration and severity of drought. As the past several fire seasons in California make clear, hot drought sets up wildfire risk like nothing else. And an unusually wet season doesn’t always help, since it can encourage excessive grass and other plants to grow, only to become highly flammable fire fuel when it dries out.

Climate change alters where snow and rain fall, and how long snow can persist and soak into the soil. Plants dry out rapidly under hotter temperatures if rain and soil moisture can’t compensate. As the planet warms, trees are weakening and dying at increasing rates, a trend that is clearest in California and New Mexico. As a result, climate-stressed vegetation is burning in unusually large, severe wildfires across the West.

Climate change also alters the zones in which plants can live successfully. As Earth’s climate changes, climate zones will shift around the planet, resulting in large-scale landscape change. And when vegetation is no longer growing in its preferred climate zone, the odds of disease, insect infestation, death and wildfire increase.

Reducing risks and making forests healthier

The most extreme way to reduce wildfire risk would be to remove all vegetation from the landscape. So why don’t we just clear-cut forests? The answer is that they provide us with all kinds of valuable benefits.

People live near forests because they value natural views and recreation opportunities. Forests also store large quantities of carbon, so we need them in order to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement and to prevent the planet from warming even faster.

Healthy forests capture and filter drinking water for more than 68,000 communities across the United States. They also maintain biodiversity by providing habitat for numerous species of plants, animals, fish and birds. And of course, forests can provide wood products, tourism and other traditional services.

The challenge is to optimize forest benefits through innovative management techniques that can also help reduce wildfire risks. Often, intentional “prescribed” burns can be used to restore forests to a more natural, healthy state by reducing buildups of dead vegetation and underbrush.

Unfortunately, climate change is making some prescribed fires harder to conduct safely. And increasingly people object to putting surrounding forests, buildings and communities at risk during prescribed burns, as well as the impacts of smoke, particularly for those with respiratory issues.

Mechanical and hand thinning of forests can also improve forest health in some circumstances. But thinning can be expensive, so forest managers need to find innovative ways to pay for it.

Some Southwest communities, including Albuquerque and Phoenix, help subsidize forest management in order to protect their water supplies. Experts have proposed expanding carbon markets to reward those who manage forests in ways that maximize the storage of carbon in vegetation and soils.

Benefits of climate and forest management action

Ultimately, protecting forests and taking action to slow climate change are complementary. Innovative approaches to forest management will reduce wildfire risks in the near term and enhance many other services provided by forests and fire-prone landscapes. Over the longer term, curbing climate change – mainly by keeping fossil fuels in the ground – will ease the warming and drying trends that are making large parts of the United States so flammable.

And all of these actions will improve safety, economic well-being and quality of life for people who live and work in fire-prone landscapes.![]()

Jonathan Overpeck, Samual A. Graham Dean, and William B. Stapp Collegiate Professor of Environmental Education, School for Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.