Policymakers will need to step up to the challenges caused by significant shifts in fish species distributions caused by climate change.

Tropical countries stand to lose the most fish species due to climate change, with few if any stocks replacing them, according to a study published in the journal Nature Sustainability. This could pose a serious governance challenge that warrants careful policy-making, the researchers say.

As sea temperatures rise, fish species migrate towards cooler waters to maintain their preferred thermal environments.

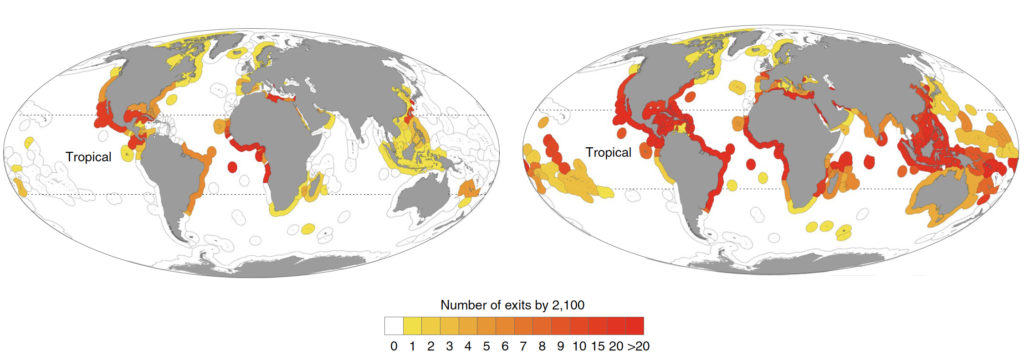

Jorge García Molinos of Hokkaido University and colleagues in Japan and the USA developed a computer model to project how the ranges of 779 commercial fish species will expand or contract under a moderate and more severe greenhouse gas emissions scenario between 2015 and 2100, compared to their 2012 distribution.

The model showed that, under a moderate emissions scenario, tropical countries could lose 15% of their fish species by the year 2100. If a more high-end emissions scenario were to occur, they could lose more than 40% of their 2012 species.

The model projects northwest African countries could lose the highest percentage of species; while Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and Central America could experience steep species declines under the worst of the two climate scenarios.

The scientists wondered if existing regional, multi-lateral or bilateral policies contain the necessary provisions to adequately manage climate-driven fish stock exits from each countries’ jurisdictional waters (exclusive economic zones [EEZs]). They analyzed 127 publicly available international fisheries agreements. None contained language directly related to climate change, fish range shifts, or stock exits. Although some included mechanisms to manage short-term stock fluctuations, existing agreements also failed to contain long-term policies that prevent overfishing by nations losing fish stocks.

García Molinos and his colleagues suggest fair multilateral negotiations may be necessary among countries benefiting from the shift in fish species and those losing from it. Tropical nations in particular should highlight compensation for fishery damage during these negotiations recurring to international frameworks such as the Warsaw International Mechanisms for Loss and Damage, which aims to address losses caused by climate change. This information should also be highlighted to other financial schemes, such as the Green Climate Fund, which have been set up to assist developing countries to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change.

“The exit of many fishery stocks from these climate-change vulnerable nations is inevitable, but carefully designed international cooperation together with the strictest enforcement of ambitious reductions of greenhouse gas emissions, especially by the highest-emitter countries, could significantly ease the impact on those nations,” García Molinos concludes.