The image messaging service Snapchat is particularly popular among young adolescents, and the recent release of its latest feature – Snap Map – provoked widespread concern among parents, and protests from child protection agencies. Snap Map enables users to monitor their friends’ movements, and determine – in real time – exactly where their posts are coming from (down to the address). Many social media users also expressed their indignation, referring to the app as “stalking software.”

“However, Snap Map is just one of a range of apps that allows social network users to be monitored without their knowledge and with pin-point accuracy,” says Professor Neil Thurman of the Institute for Communications Studies and Media Research at LMU. “Indeed some of these apps far exceed Snap Map in their surveillance capabilities, and are able to track individuals over time and across multiple social networks.”

In his latest study, which has been published in Digital Journalism, Thurman lists a range of such apps – including Echosec, Dataminr, Picodash, and SAM. While Snapchat’s Snap Map is aimed at the public, many of the other social media monitoring apps are aimed at professional users, including the security forces, journalists, and marketeers.

Help with verification

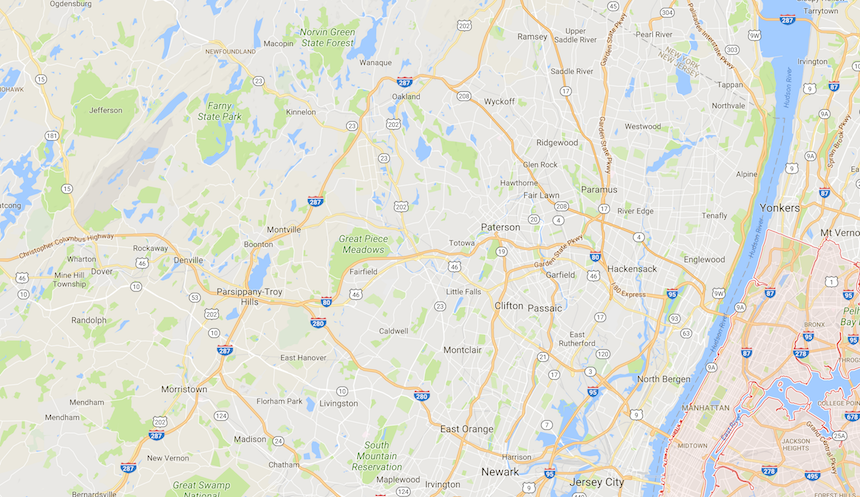

LMU says that Thurman analyzed how journalists reacted to these new tools for locating and filtering content on social networks, and monitoring the activities and movements of its authors. It turns out that these apps are particularly useful in verification, enabling journalists to judge whether witness accounts were actually posted from the supposed scene of the action.

“These apps have been welcomed by some journalists who see them as an ‘early warning system’,” says Thurman, but they also have consequences for users’ personal privacy, he argues. In the course of his study, he interviewed journalists who were given an opportunity to experiment with some of these apps professionally. One said that being able to track the locations of individual social media users felt “slightly morally wrong and stalker-esque.”

Fear of negative publicity

However, reservations like this are apparently not universal. “One of the apps my report describes, Geofeedia, was used by hundreds of law enforcement agencies, promoted as giving the police the power to “monitor” – via social media – trade union members, protesters, and activist groups, who the company described as being an “overt threat.” The Geofeedia controversy led to its demise, with social networks refusing to persist in supplying the app with a pipeline of posts for fear of further negative publicity.

According to an article in the business magazine Forbes, cited by Thurman, the sheer number of apps that have been built on their platforms makes it impossible for the leading social media networks to prevent this form of social surveillance. “As we’ve seen with the launch of Snap Map, social media surveillance is not going to go away,” he warns. “Although we might now know how to go ‘ghost’ on Snapchat, how many of us know that our other social media posts could be betraying our whereabouts to the thousands of organizations around the world using social media monitoring apps most have never heard of?”

— Read more in Neil Thurman, “Social Media, Surveillance, and News Work: On the apps promising journalists a ‘crystal ball’,” Digital Journalism (18 July 2017): 1-22 (doi: org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1345318)