The mystery ailment that has afflicted U.S. embassy staff and CIA officers off and on over the last four years in Cuba, China, Russia and other countries appears to have been caused by high-power microwaves, according to a report released by the National Academies. A committee of 19 experts in medicine and other fields concluded that directed, pulsed radiofrequency energy is the “most plausible mechanism” to explain the illness, dubbed Havana syndrome.

The report doesn’t clear up who targeted the embassies or why they were targeted. But the technology behind the suspected weapons is well understood and dates back to the Cold War arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. High-power microwave weapons are generally designed to disable electronic equipment. But as the Havana syndrome reports show, these pulses of energy can harm people, as well.

As an electrical and computer engineer who designs and builds sources of high-power microwaves, I have spent decades studying the physics of these sources, including work with the U.S. Department of Defense. Directed energy microwave weapons convert energy from a power source – a wall plug in a lab or the engine on a military vehicle – into radiated electromagnetic energy and focus it on a target. The directed high-power microwaves damage equipment, particularly electronics, without killing nearby people.

Two good examples are Boeing’s Counter-electronics High-powered Microwave Advanced Missile Project (CHAMP), which is a high-power microwave source mounted in a missile, and Tactical High-power Operational Responder (THOR), which was recently developed by the Air Force Research Laboratory to knock out swarms of drones.

Cold War origins

These types of directed energy microwave devices came on the scene in the late 1960s in the U.S. and the Soviet Union. They were enabled by the development of pulsed power in the 1960s. Pulsed power generates short electrical pulses that have very high electrical power, meaning both high voltage – up to a few megavolts – and large electrical currents – tens of kiloamps. That’s more voltage than the highest-voltage long-distance power transmission lines, and about the amount of current in a lightning bolt.

Plasma physicists at the time realized that if you could generate, for example, a 1-megavolt electron beam with 10-kiloamp current, the result would be a beam power of 10 billion watts, or gigawatts. Converting 10% of that beam power into microwaves using standard microwave tube technology that dates back to the 1940s generates 1 gigawatt of microwaves. For comparison, the output power of today’s typical microwave ovens is around a thousand watts – a million times smaller.

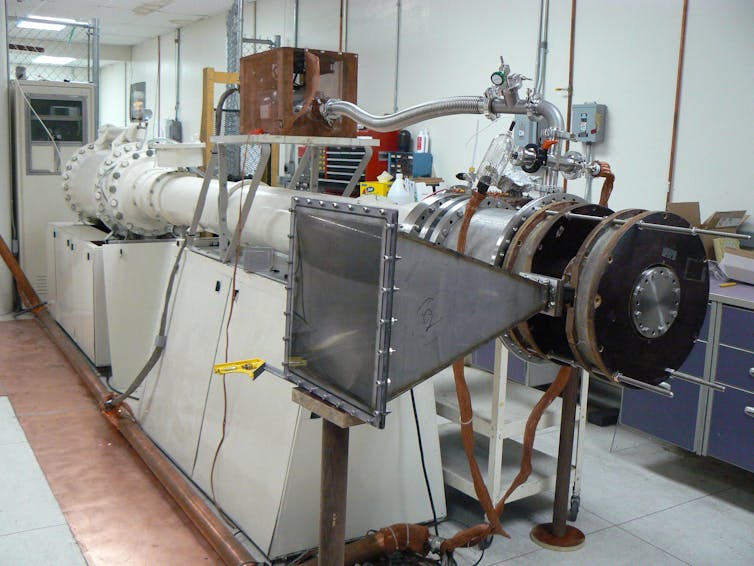

The development of this technology led to a subset of the U.S.-Soviet arms race – a microwave power derby. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, I and other American scientists gained access to Russian pulsed power accelerators, like the SINUS-6 that is still working in my lab. I had a fruitful decade of collaboration with my Russian colleagues, which swiftly ended following Vladimir Putin’s rise to power.

Today, research in high-power microwaves continues in the U.S. and Russia but has exploded in China. I have visited labs in Russia since 1991 and labs in China since 2006, and the investment being made by China dwarfs activity in the U.S. and Russia. Dozens of countries now have active high-power microwave research programs.

Lots of power, little heat

Although these high-power microwave sources generate very high power levels, they tend to generate repeated short pulses. For example, the SINUS-6 in my lab produces an output pulse on the order of 10 nanoseconds, or billionths of a second. So even when generating 1 gigawatt of output power, a 10-nanosecond pulse has an energy content of only 10 joules. To put this in perspective, the average microwave oven in one second generates 1 kilojoule, or thousand joules of energy. It typically takes about 4 minutes to boil a cup of water, which corresponds to 240 kilojoules of energy.

This is why microwaves generated by these high-power microwave weapons don’t generate noticeable amounts of heat, let alone cause people to explode like baked potatoes in microwave ovens.

High power is important in these weapons because generating very high instantaneous power yields very high instantaneous electric fields, which scale as the square root of the power. It is these high electric fields that can disrupt electronics, which is why the Department of Defense is interested in these devices.

How it affects people

The National Academies report links high-power microwaves to impacts on people through the Frey effect. The human head acts as a receiving antenna for microwaves in the low gigahertz frequency range. Pulses of microwaves in these frequencies can cause people to hear sounds, which is one of the symptoms reported by the affected U.S. personnel. Other symptoms Havana syndrome sufferers have reported include headaches, nausea, hearing loss, lightheadedness and cognitive issues.

The report notes that electronic devices were not disrupted during the attacks, suggesting that the power levels needed for the Frey effect are lower than would be required for an attack on electronics. This would be consistent with a high-power microwave weapon located at some distance from the targets. Power decreases dramatically with distance through the inverse square law, which means one of these devices could produce a power level at the target that would be too low to affect electronics but that could induce the Frey effect.

The Russians and the Chinese certainly possess the capabilities of fielding high-power microwave sources like the ones that appear to have been used in Cuba and China. The truth of what actually happened to U.S. personnel in Cuba and China – and why – might remain a mystery, but the technology most likely involved comes from textbook physics, and the military powers of the world continue to develop and deploy it.

Edl Schamiloglu, Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Associate Dean for Research and Innovation, School of Engineering, University of New Mexico, University of New Mexico

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.