A review of Yasheng Huang, “The Rise and Fall of the EAST: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success, and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline” (Yale, 2023)

I meandered along a tree-lined path at Tsinghua University one night in spring 2023 with a classmate I met while conducting interviews for my thesis on U.S.-China technology competition. This activity became a regular occurrence for us: wandering around campus after dark, eating snacks, and chatting about everything from mindfulness to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). That particular evening, we discussed the gaokao: China’s college entrance test. This assessment, administered through local governments once a year, dictates all higher education in China.

“Should a standardized, universal metric determine such a monumental life step?” my friend asked me.

He leaned towards no; the gaokao system undermined China’s thought and talent diversity. Students spend their entire pre-college lives preparing for the test, providing them no time to explore other interests. Thus, this exam homogenized ideas and stifled innovation.

I agreed but argued that the U.S. equivalent—an opaque combination of high school grades, SAT/ACT scores, extracurricular activities, parents’ financial contributions to an institution, and essays—perpetuated inequality and deepened societal divides. We discussed the options, landing at no definitive solution and wandering for hours until we parted at my dorm entrance.

Our conversation, unbeknownst to us, mirrored the crux of Yasheng Huang’s “The Rise and Fall of the EAST: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success, and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline.” In this new book, Huang, an MIT Sloan School of Management professor, outlines how, over two millennia and through four hallmark features—exams, autocracy, stability, and technology (EAST)—the tension between “scale” (homogeneity and bureaucratic size) and “scope” (heterogeneity and thought diversity) has tugged China in polarizing directions. This friction that the gaokao embodies shaped modern China.

The tension between scale and scope arose in the Qin dynasty (221-207 BCE). Twelve years after Emperor Qin Shi Huang expanded his empire to previously divided lands and “united” China, the Dazexiang uprising catalyzed the end of his reign. When Chen Sheng and Wu Guang, two Qin army officers, arrived late to a posting due to flooding and received the death penalty, they and 900 other conscripts rebelled. Qin’s legalistic regime failed to account for this natural factor in their tardiness. Under the Qin law, they broke the law and must be punished. (Legalism, one of the early Chinese philosophical schools, imposed strict guidelines and rules over what we would today view as a Hobbsian conception of a chaotic populace.)

Emperor Qin crafted this conscription punishment law, among many others, when he ruled only a small region of China. This area had uniform topography, stable environmental conditions, and a homogeneous population. After conquering the five Zhao territories, his citizenry and land diversified, but his laws remained consistent. The strict Qin governance failed to account for the inconsistencies in the new empire, such as the flood seasons. In the Dazexiang case, a logical mandate to encourage timeliness in a small region became an unjust, arbitrary punishment that incited the empire’s fall. Thus, the Qin empire’s magnitude (“scale”) without the governance framework to account for the empire’s diversity (“scope”) eroded the Qin dynasty.

This dynamic existed beyond China. Many other kingdoms, such as the Roman and Mongol empires, crumbled after expansion. Yet, in 587 CE, the Sui dynasty rulers of China discovered what Emperor Qin and the Western rulers could not: how to extend control to new regions and diverse populations without fragmentation.

An imperial civil service examination called the keju (科举) provided the solution to maintain autocratic power over an extended sphere of influence. While a form of the test—the chaju—had existed since the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), the Sui first systematized this exam to elect the emperor’s officials. This test provided an upward trajectory to every male citizen regardless of creed, status, or income. Studying the exam’s contents (at the time, the Confucian classics) homogenized thought, culture, and religion through a uniform code of conduct. The test also provided a single focal point for citizens’ lives. Thus, the keju helped the emperor maintain control by systematizing a universal doctrine and limiting recreational time, which could lead to counterculture or revolution.

Over the next thousand years, the keju evolved. It expanded beyond China to nations across Asia, such as Vietnam from 1075 to 1919, Korea from 958 to 1894, and Japan between the 8th and 12th centuries. Within China, emperors revised, rewrote, and warped the keju—with various degrees of success. During the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127 CE), for instance, the introduction of partial anonymization, a preparatory system to prepare a more diverse set of testers, and a triennial schedule decreased corruption and increased equal access to the exam.

But the exam struggled under other leaders. During the Yuan dynasty (1279 – 1368 CE), officials briefly suspended the keju and then, after reinstating it, only allowed lower-level positions to recruit from the exam. In the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the last Chinese dynasty, corruption tore apart the system. Officials auctioned off keju degrees and political positions during times of strife, such as the Taiping Rebellion (1851-1864), when the government sold an unprecedented number of degrees to fund anti-insurrection efforts.

Throughout China’s development, a pattern emerged: During stable periods, the keju helped China maintain control over large populations and areas. Conversely, eras that deemphasized the keju resulted in chaos but also innovation.

And here lies the conundrum of the keju: While this test allowed for a larger scale of influence, it limited the empire’s scope. By increasing order, it stifled diversity of thought, culture, and ideas. The fluctuations in the keju ultimately shaped Huang’s last three categories: autocracy, stability, and technology.

Huang contends that the keju system maintained China’s autocratic longevity. This theory contradicts other scholars—such as Dingxin Zhao, a Chinese sociologist at the University of Chicago, and Ping-ti Ho, a late Chinese American historian—who argue that China’s autocratic durability derives from China’s official Confucian orthodoxy and China’s robust agricultural system, respectively. Huang dismisses these theories. First, he argues that orthodoxy alone cannot sustain an autocracy, citing that the Roman Empire fell due to Christianity and the Qin dynasty collapsed under a ubiquitous legalistic orthodoxy. Second, Huang notes that agriculture and geography remained relatively consistent throughout Chinese history, including during autocratic governance failures, such as the Han-Sui interregnum (280-581 CE). Instead, he posits that the keju process facilitated a symbiotic trust between the rulers and the people. The keju offered individuals a means to improve their lives through talent and education instead of money and familial connections. Thus, people bought into the autocracy because it gave them a fair chance to participate.

Throughout Chinese history, innovation has stagnated during periods with an over-emphasis on examination, stability, and autocracy. While many scholars cite the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) as China’s technological decline after a period of affluence and openness during the Song and Tang dynasties, Huang rejects this theory. Instead, he points to Joseph Needham’s 1969 studies, known as the “Needham Question,” that explore China’s technological development. He concludes that China’s scientific stagnation dates back further than the Ming.

Huang created a novel method, the Chinese dynasty inventiveness (CDI) index, to measure the “inventiveness of a dynasty.” This system records the number of inventions in a particular dynasty divided by its population (per a million people). Through these calculations, Huang found that innovation started to decline when the Sui institutionalized the keju in 589 CE , almost a thousand years before the Ming. He explains that people spent so much time preparing for this test that they lacked the innovation and creativity necessary for technology to develop. As Huang described, “The Sui dynasty holds the key to one of the most enduring enigmas in the history of technology—the collapse of Chinese technological supremacy.”

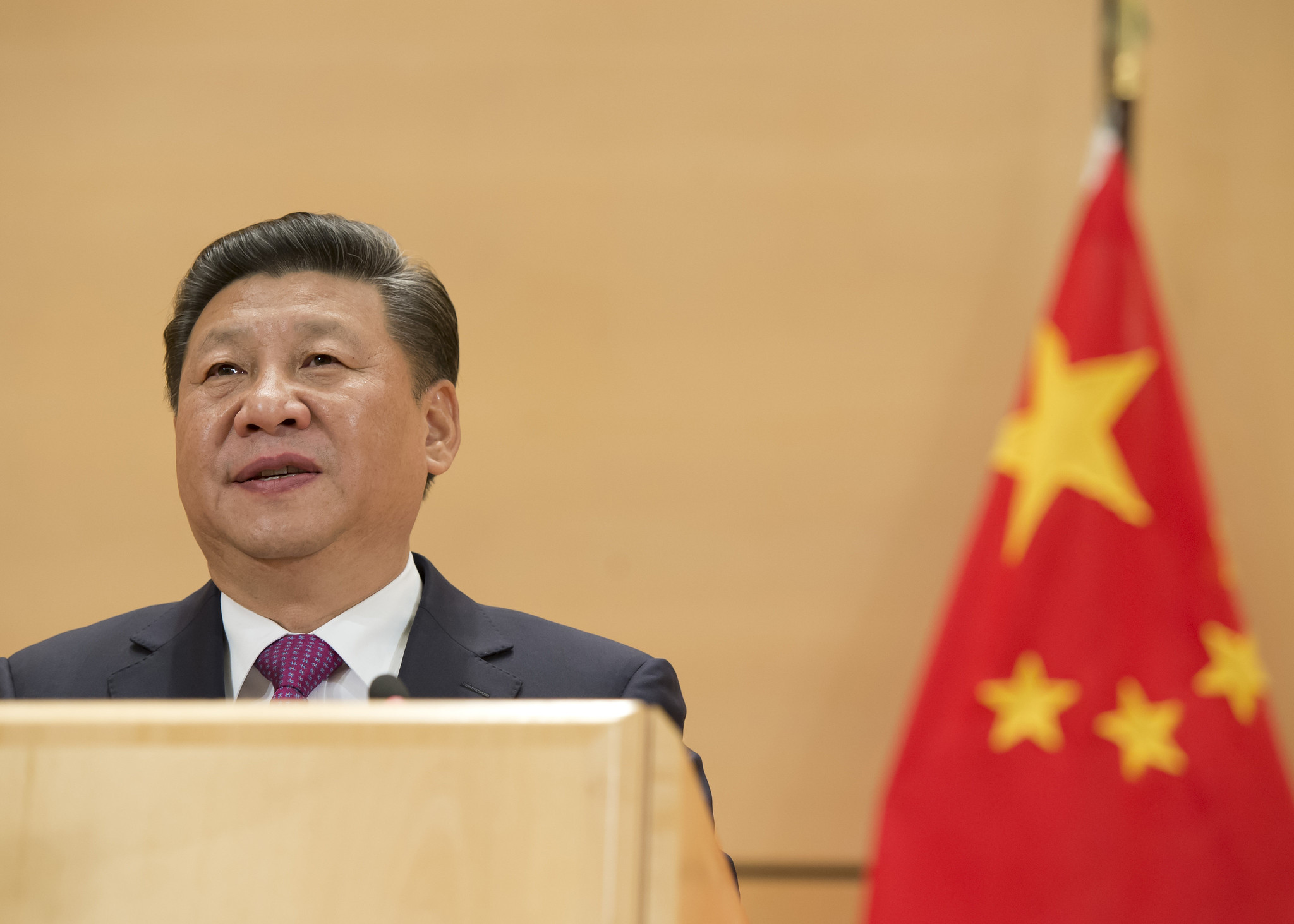

The keju test exemplifies how China’s obsession with stability and autocracy often came at the cost of innovation. The few leaders, such as Deng Xiaoping, who maintained the delicate balance between scale and scope raised standards of living in China and modernized the nation. Xi Jinping has knocked China off this precarious path and, once again, overemphasized scale.

Xi has further standardized China’s education system, rewritten history, and narrowed the incentive system for rising party cadres to focus on party loyalty. He erased term limits in spring 2023, which Huang characterizes as an example of “Tullock’s curse,” the observation, named after the American economist Gordon Tullock, that an autocratic system’s handoff of power often ends with chaos. Succession failures in the early CCP era—Liu Shaoqi (the first anointed successor to Mao Zedong), Lin Biao (Mao’s second successor in 1969), and Hu Yaobang—embody this prediction. Term limits, introduced during the Deng era, helped China manage Tullock’s curse. Removing term limits stripped the CCP of a standardized power transfer system; what may have seemed to enhance stability through a constant leader actually introduced uncertainty about how and when the next ruler would arise.

My Tsinghua friend noticed that Xi’s over-emphasis on exams, stability, and autocracy undermined modern China’s innovation and led to discontent. Especially since 2018, Xi has cracked down on the plurality of thought, religion, and expression, with devastating consequences. The three-year “Zero-COVID” lockdown and unstable market practices that eradicated any semblance of civil society further restricted China’s entrepreneurial innovation. While some media outlets home in on China’s plentitude of research papers and scores of engineers as reasons to worry about China’s technological prowess, Huang’s analysis suggests otherwise.

He predicts a stagnant China that suffers under Xi’s emphasis on scale and condemnation of meaningful scope. While China has 1.4 billion people, a gross domestic product of over $17 trillion, and cities with names most foreigners have never heard of that nevertheless put Manhattan’s skyline to shame, Huang argues that China lacks one crucial ingredient for actual technological superiority: diversity. Xi has “Han hua”-ed (Han-Chinese washed) everything from local culture and food to college curriculums and newspapers in China.

Huang notes that Xi accelerated China’s destructive reliance on scale, but Huang does not hold fatalistic views about China’s future. He points to China’s meandering history as an indication that China will once again recover. China will not continue down this path forever. And the important part, he argues, is for the rest of the world to allow China to bounce back on its own.

– Christina Knight, Published courtesy of Lawfare.