Experiments by ETH Zurich computer security researchers showed that smartphones can be manipulated to allow the owner to ride Swiss trains for free. The researchers also highlighted ways of curbing such misuse.

- Users with sufficient expertise can manipulate their smartphone’s location data.

- This is how ETH Zurich researchers managed to trick the Swiss federal railways (SBB) app. They showed that it would be possible to ride the rails for free.

- The researchers informed SBB. The company says it has now taken appropriate action. Now, this kind of ticket fraud would be detected at least after the fact and penalised.

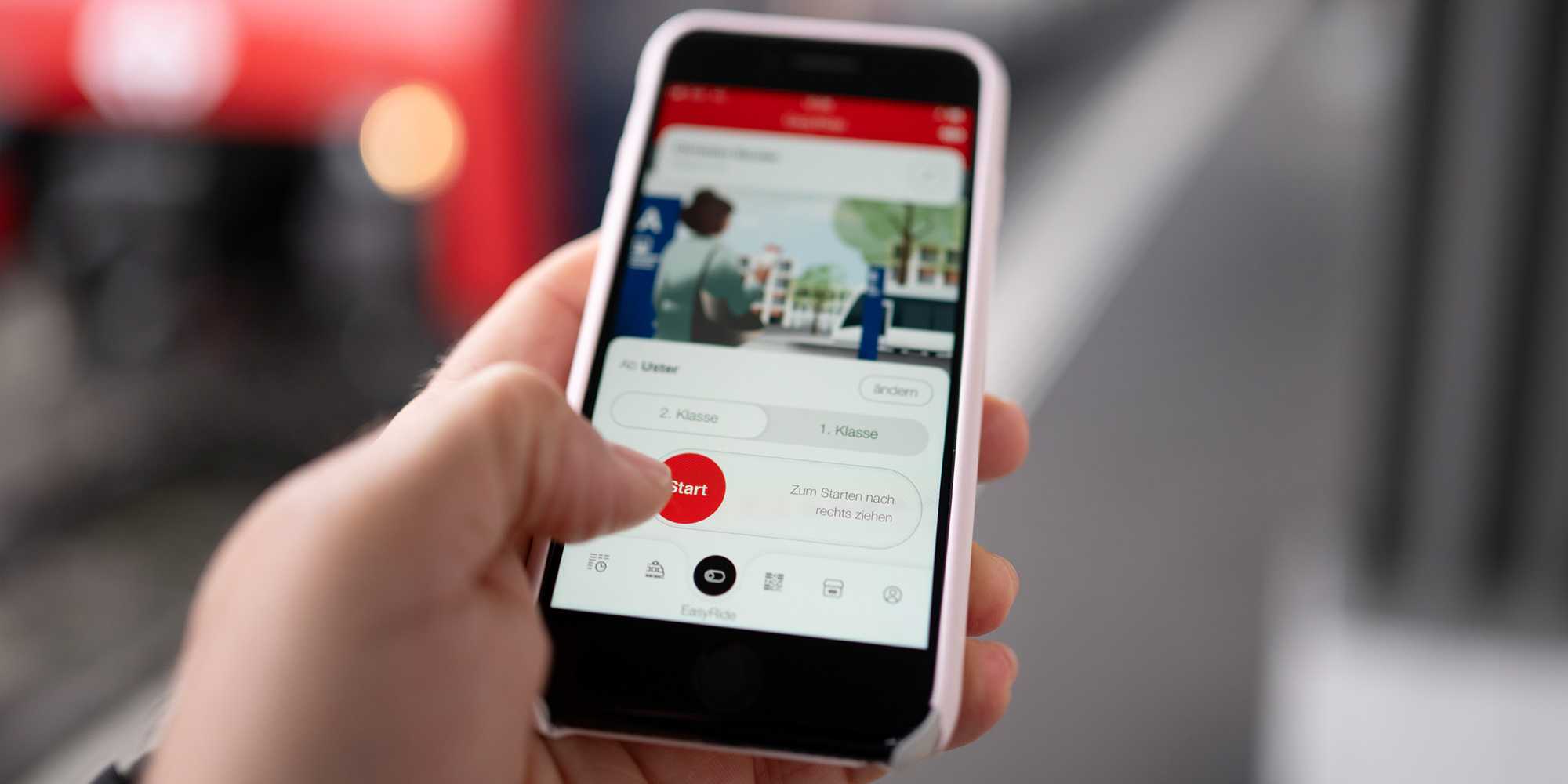

It makes travelling by train, bus and tram super easy: instead of buying a conventional ticket, people using the EasyRide function in the SBB app can start their journey with a single swipe on their smartphone. Once at their destination, they swipe the other way to check out again. A QR code visible in the app serves as their ticket. It confirms to the ticket inspector that they have activated the EasyRide function. During the journey, the app continuously transmits location data to an SBB server. The server uses this data to calculate the route travelled, allowing SBB to then bill the user for the fare.

EasyRide has been available throughout Switzerland since 2018. Last year, however, ETH Zurich researchers managed to trick the system. The EasyRide function relies on smartphone location data, but users with specialised knowledge can manipulate this information. SBB says that it can now detect this kind of ticket fraud.

Ticket inspectors noticed nothing

A year ago, the situation was different: researchers and students belonging to the group led by Kaveh Razavi, Professor of Computer Security at ETH Zurich, suspected that the EasyRide function could be outsmarted, and so they put their suspicion to the test. They altered a smartphone so that its GPS data – which the SBB app accesses – was overwritten with fake but realistic-looking location information. This data simulated that the user was only moving around in a small area in a city without using public transport. The researchers used two approaches: In one case, a programme generated the fake location data directly on the smartphone. In the other case, the smartphone was connected to a server running the SBB app. This server generated fake location data and transmitted the EasyRide QR code to the smartphone.

The ETH researchers tested their specially prepared smartphone on several train journeys from Zurich to the capital of a neighbouring canton. Their trickery went unnoticed by the ticket inspector and they were not contacted by SBB afterwards. Rather, SBB calculated the costs of the fake small-scale movements for which no public transport was used. In other words, the researchers were able to travel free of charge with EasyRide. They emphasise that while they showed the ticket inspector the EasyRide QR code, they were also in possession of a valid ticket at all times.

Today’s location data is untrustworthy

Although a person must have specialist knowledge to manipulate their smartphone, Razavi says, the necessary expertise is common among students doing a Bachelor’s in computer science. With the right amount of criminal ambition, it would even be possible to offer a smartphone program combined with an online service to supply tricksters lacking the requisite IT skills with fake, yet plausible, location data.

“The basic truth is that smartphone location data can be manipulated and cannot be relied upon entirely,” says Michele Marazzi, a doctoral student in Razavi’s group. “So, app developers shouldn’t treat this data as trustworthy. That’s what we wanted our project to highlight.” When location data is used as the basis for calculating and billing a service, as in the SBB app, more attention must be paid to this vulnerability.

Comparison with trustworthy data required

The researchers propose two ways of solving the problem: either the location data must be verified using reliable positioning notifications, or smartphones must be designed to make such manipulation much more difficult. For the first approach, it would be possible to compare the data provided by the user’s smartphone with location data that the transport company trusts – such as that provided by the vehicle or a mobile device carried by the ticket inspector.

The second approach is trickier: it would involve getting developers of smartphone hardware and operating systems on board and convincing them to deploy a new type of tamper-proof localisation technology. “But until that happens, all services that are obliged to rely on location information provided by smartphones have no choice other than to verify this data as best they can using a trustworthy source of location data,” says ETH professor Razavi.

The ETH researchers informed SBB about the vulnerability in the EasyRide function, kept in touch with the company’s experts over the past year and presented them with their solutions for making the function more secure.

SBB emphasises that it is an offence to use the EasyRide function in combination with manipulated location data. According to SBB, the company has improved the verification of the location data transmitted to the server following the information provided by the ETH Zurich research team. Instances of manipulation are now detected after the fact and offenders are prosecuted. For security reasons, SBB is not disclosing exactly how the checks are carried out.