In 2014, when an anonymous caller cost the U.S. Coast Guard roughly $500,000 by sending first responders on unnecessary rescue missions twenty-eight times, the agency asked the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) for help.

In 2014, when an anonymous caller cost the U.S. Coast Guard roughly $500,000 by sending first responders on unnecessary rescue missions twenty-eight times, the agency asked the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) for help.

The U.S. Coast Guard receives more than 200 false distress calls a year over its Very High Frequency (VHF) radio channel 16 — the mariner’s “911” — and the number is growing.

These false calls are not simply a nuisance: Every distress call the Coast Guard receives compels the federal agency to launch an expensive search-and-rescue effort involving at a minimum a small rescue boat, a C-130 fixed-wing aircraft or rescue helicopter, and the several Coast Guardsmen to operate them. The cost of each outing can run from $10,000 to $250,000. Small boats cost typically $4,500 per hour to operate and helicopters – $16,000.

“I have seen responses run into the three figure numbers quite often,” said Marty Martinez, special agent in charge for the Chesapeake Region of the Coast Guard Investigative Service in Portsmouth, Virginia.

The penalty for transmitting a hoax distress call to the Coast Guard is up to six years in prison, a $250,000 fine, a $5,000 civil fine, and reimbursement to the Coast Guard for the cost of performing the search.

“The men and women of the Coast Guard put themselves at risk every time our surface and air assets respond to a call for assistance. Hoax callers place Coast Guardsmen at unnecessary risk,” said Martinez. “Also, hoax calls interfere with legitimate search and rescue cases, diverting assets from being available to help actual mariners in distress.”

Besides wasting taxpayers’ money in fruitless rescue operations, the pranksters also divert manpower and equipment from other critical missions such as drug interdiction and other law enforcement efforts.

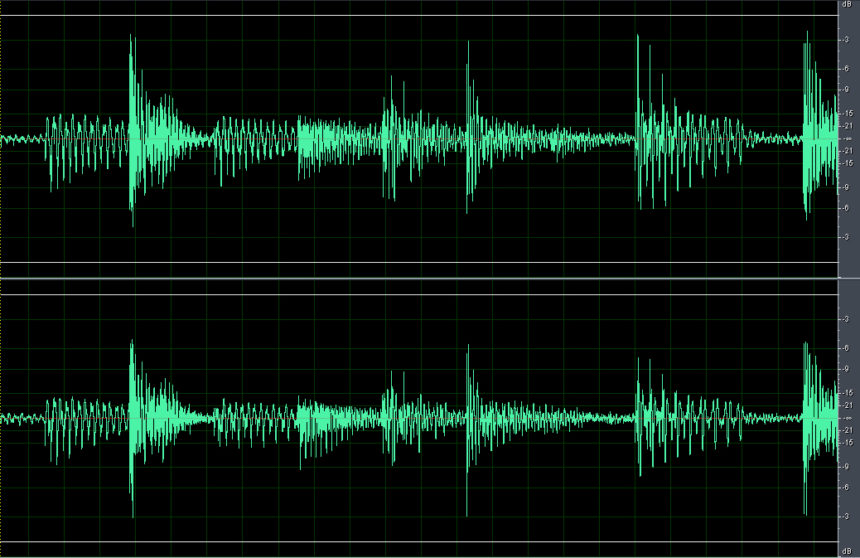

S&T notes that in December 2014, S&T connected the Coast Guard with Dr. Rita Singh, who has collected a large repository of sound recordings of different voices and environments over the years. “They were looking for any information we could provide from the caller’s audio signal because that was the only evidence they had,” Singh said. She is a senior systems scientist at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU)’s Language Technologies Institute, which partners with the Center for Visualization and Data Analytics, an S&T Office of University Programs (OUP) Center of Excellence.

“We have a great partnership with S&T, and we knew CMU had the capability for voice forensics,” said Alan Arsenault, chief of the Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance branch at the Coast Guard Research and Development Center.

“We looked at other technology such as mobile direction-finding capabilities and social media analyses tools, but this was really panning out to give us some great details for building a case file,” Arsenault said.

In the event of a hoax call, the towers of Rescue 21, a communications management system for the Coast Guard, triangulate a geographical area. Coast Guard Investigative Service special agents will interview local mariners and seek information from local law enforcement in that area, seeking any information that may be useful in identifying the caller. The Coast Guard can even have the recorded call played by the local media to see if anyone recognizes the voice. “It is basically good old detective work – only we are trying to identify a logical suspect based on a voice,” Martinez said. Then Dr. Singh comes in.

The Coast Guard specifically asked Singh to run the hoax calls through her repository, said Matthew Clark, Director of the S&T’s OUP. “She came up with this long list of things she could tell S&T and the Coast Guard about the physical characteristics of the perpetrator and his environment.” The list included descent, age, height and weight background noise and the type of room where the call was made. “It is all based on voice and noise.”

“Profiling humans from their voice is a new area of research in voice forensics that is massively driven by recent advances in artificial intelligence,” said Singh.

The only evidence unidentified hoax callers leave behind initially is the raw recording. However, Singh’s team can deduce many aspects of the callers using artificial intelligence techniques. Besides the obvious age, gender and ethnicity, they can also glean physical characteristics, health, emotional state, and even a person’s educational level and socioeconomic status. The researchers can also profile the place from which the perpetrator makes the call – possible location, room size, type of objects present and the material of the walls, ceiling and floor – all based on background noise and voice echo.

“All this is useful information when you start identifying potential suspects and ask, ‘Does this person meet the characteristics Dr. Singh’s team has pointed out?” Martinez said.

But the Coast Guard still has to identify logical suspects. They go back to Singh with recordings of potential callers to match to the hoax call. If there is no match, Martinez’s team has to reevaluate. If there is a match, they have to develop the evidence to place the suspect with the device at the location where the hoax call was made. “Although there is more investigative work to do after a voice match is made, now we are more focused in our efforts based in part on the voice analytics provided by CMU and Dr. Singh,” he said.

This collaboration is already producing results. “In several cases, Singh not only helped exclude potential suspects, but she also narrowed down our suspects to one or two individuals,” Martinez said.

Not a single case with voice forensic evidence has gone to trial yet, but Martinez thinks they are getting very close. He believes that very soon he will be able to include voice analytics as part of the evidence package in court. Currently, voice analytics has helped the Coast Guard focus on a suspect from the Maryland area. “We are slowly bringing the case to conclusion and hopefully prosecution.”

If the investigations are successful, this could lead to more widespread use of voice forensics. The resulting evidence could be used in well-publicized criminal prosecutions to deter other would-be hoaxers.

“Voice forensics is at the tipping point of being used as a piece of evidence, similarly to back in the day when DNA was not yet accepted as evidence,” said Arsenault.