Want to try your hand at negotiating during a crisis? Think you have a plan that could get the U.S. out of Afghanistan? Confident you could keep a nation secure when multi-party international diplomacy is more important than warfare? Strategy-based board games let you test your political and military acumen right at your kitchen table – while also helping you appreciate how decision-makers are limited by the choices of others.

For centuries, military trainers have used board games as tools to help recruits and leaders alike understand fundamental principles of warfare. In the early 19th century, for instance, the Prussian military required its officers to play a board game called “Kriegsspiel.” The high command realized that while individual officers might understand the principles of combat, they might not know how to apply them when facing an actual opponent. And in stepping back and analyzing what happened after a game was over, they might see what factors really mattered, and how the players’ choices influenced each other.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the U.S. Navy used war games to design military plans against potential adversaries. By the time World War II arrived, U.S. Admiral Chester Nimitz observed, the conflict “had been reenacted in the game rooms at the Naval War College by so many people and in so many different ways, that nothing happened during the war that was a surprise … absolutely nothing except the kamikaze tactics toward the end of the war.”

War gaming continues to offer opportunities for scholars to better understand security dynamics. A growing cadre of experts have turned to war games to show how a Russian invasion of the Baltics might play out or how a shift to robotic warfare might lead to fewer military crises. In my own research, I have used war games to better understand and prepare for what are sometimes called “low-frequency, multi-factor” events – security scenarios that have lots of variables but have rarely, or never, happened, such as a full-scale cyber-conflict between the U.S. and China.

War games are useful intellectual aids because they force players to make decisions under pressure. While people may intellectually understand a problem, gaming forces them to think even harder. As the Nobel Prize-winning economist Thomas Schelling put it, “one thing a person cannot do, no matter how rigorous his analysis or heroic his imagination, is to draw up a list of things that would never occur to him.” By facing off against opponents over a well-designed war game, people can come to see how political and military structures interact and appreciate the trade-offs and complications that come with making decisions in a competitive environment.

With this in mind, I present some of my favorite war games. They not only are gripping to play but also offer players a window into some core elements of modern security politics. They are rated for players, time and complexity (where “Monopoly” would score a 1 out of 5). I have no financial or professional relationships with any of the game publishers listed; these games are just personal favorites.

Asymmetric warfare – ‘Washington’s War’

2 players, 2-3 hours, complexity: 2.5

Wars between big global powers and smaller nations don’t always go the way planners expect. For instance, the Trump administration has decided to take a very hard line with Iran, and there is an increased possibility of war. But assuming the U.S. goliath would automatically win underestimates the advantages that invaded states have. In “Washington’s War,” the British player has a large army and purse, and the ability to bludgeon almost any colonist on the board – if only he could engage them. The problem is that the colonial player can move across the board like a fish through water and needs to do less to win. “Washington’s War” shows that warfare is fundamentally about domestic and international political support, and that given the right leadership and hit-and-run tactics, smaller players can run out the clock and prevail.

Nuclear brinkmanship – ‘13 Days’

2 players, 45 minutes, complexity: 2

Continued U.S. concerns about North Korean and Russian threats mean that the terror of nuclear annihilation sadly remains present. But this threat is also puzzling. Considering the suicidal damage of a full exchange, how can anyone make believable threats with nuclear weapons? “13 Days” offers a window into this process. Playing the role of either the USSR or the U.S. during the Cuban Missile Crisis, players attempt to take control of the political, military and media situation and emerge with the most prestige at the end of three rounds. But beware! Overplay your hand in any of the three areas without holding back, and you may go over the brink into full nuclear war.

Modern infantry combat – ‘Combat Commander: Europe’

1-2 players, 2-4 hours, complexity: 4

Although set during World War II, this game gives the player an insight into the chaos of tactical combat. Taking the role of U.S., Soviet or German commanders leading units of about 120 soldiers, players draw cards and play them to maneuver and engage their squads of men. Although the presentation is a little dry, “Combat Commander: Europe” has many features of modern warfare: suppression fire, mortars, snipers, machine gun nests, smoke, artillery call-ins and command confusion. The rules are intricate but clear and logical, while hands of cards help to simulate the strengths and weaknesses of each side. For instance, the tactically adaptive German player can adjust on the fly by discarding her whole hand, while the aggressive Soviet player receives more ambush cards. Ultimately, the game forces players to work with the resources they have, not the ones they wish for.

Counterinsurgency operations – ‘A Distant Plain’

1-4 players, 4 hours, complexity: 5

Despite recent talks with the Taliban, there appears no easy way out for forces participating in the U.S.’s longest war. Why? Designed by a former CIA operative, “A Distant Plain” offers an answer. Players take on the roles of the Kabul regime, warlords, the Taliban or U.S.-led NATO forces, each able to engage in different tasks and each subject to different – but interlinked – pressures. Should the local government agree to allow the warlords to grow opium so long as they agree not to ambush travelers on the roads? Should the Taliban try to move deep into the interior or hover at the Pakistani border? And how can the coalition player meet her competing goals of stabilizing the local regime while also drawing down troops? Undoubtedly a complex game and not recommended for beginners, this game makes it clear that “whack-a-mole” is not a meaningful strategy.

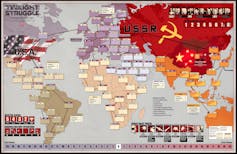

Emerging bipolarity – ‘Twilight Struggle’

2 players, 4 hours, complexity: 3.5

Many war gamers consider this the very best game ever made. The U.S. and USSR square off over 40 years of history and attempt to dominate as much of the rest of the world as possible while avoiding coming to blows directly. Drawing from three decks of cards over the course of play – early, middle and late Cold War – players receive a history lesson replete with coups, communist revolutions, Marshall Plan aid, proxy wars, oil crises, space races and the all-important China card (literally, a card). Rising tensions on the “DEFCON” track make it harder and harder to make big changes to the game board without also triggering nuclear war. Perhaps, in 80 years, “Twilight Struggle” will be republished with the U.S. and China as the antagonists.![]()

David Banks, Professorial Lecturer of International Politics, American University School of International Service

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.