President Donald Trump has announced he was considering sending the federal military into the streets of numerous American cities – above and beyond those sent to Washington, D.C. – in an effort to control the protests and violence that have emerged in the wake of the May 25 killing of George Floyd.

He has since ordered the military to be withdrawn from the capital, but has not ruled out the possibility of using troops in similar situations in the future.

Those actions have led to widespread objections – including an apology from the country’s top military official for taking part in Trump’s walk across Lafayette Square on June 1. Trump’s own former defense secretary, retired Marine General James Mattis, went farther, urging Americans to “reject and hold accountable those in office who would make a mockery of our Constitution.”

For most Americans, that kind of response could take a variety of forms, including protesting, voting and contacting elected representatives. But members of the U.S. armed forces have an additional option: They could refuse to follow the orders of their commander-in-chief if they believed those orders were contrary to their oath to the Constitution.

Legal power and moral obligations

As former officers ourselves, and as current professors of military ethics, we do not take this possibility lightly. We often discuss with our classes the fact that military members are not duty-bound to follow illegal orders. In fact, they are expected, and sometimes legally required, to refuse to obey them.

In this case, many have argued that the Insurrection Act of 1807 gives the president the legal authority to deploy the military within the United States to restore civil order. And because of the city’s unique constitutional status as a federal district, the president has already put federal troops on the streets of the District of Columbia without invoking that act.

Military members are not, however, absolved of moral responsibility simply because orders are within the limits of the law, for they also take an oath to “support and defend” and to “bear true faith and allegiance” to the Constitution.

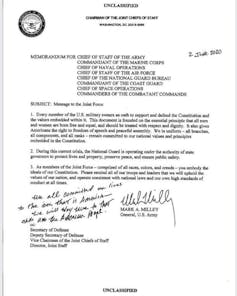

On June 2, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff – the highest-ranking uniformed officer in the U.S. military – went so far as to issue a service-wide memo reminding troops of that oath, one that may well be at odds with what the president may order them to do if he were to send them back into U.S. cities.

Civilian control and the reasons for principles

Of course, the mere fact that a military member worries about the constitutionality of an order cannot be a decisive reason to disobey. It is usually the role of those higher up the chain of command – often civilian leadership – to determine whether an order is constitutional.

That kind of concern may well have been on display in recent days when senior civilian and military officials reportedly resisted Trump’s desire for active-duty troops to get even more involved.

The U.S. military has long been dedicated to the principle of civilian control. The country’s founders wrote the Constitution requiring that the president, a civilian, would be the commander-in-chief of the military. In the wake of World War II, Congress went even further, restructuring the military and requiring that the secretary of defense ought to be a civilian as well.

Yet the underlying moral reasons that generally speak in favor of deferring to civilian leadership may not be so straightforward when it comes to federal troops on U.S. streets.

Consider, for example, the fact that John Adams and Thomas Jefferson worried about a military that would be loyal to a particular leader rather than to a form of government. Madison was concerned soldiers might be used by those in power as instruments of oppression against the citizenry.

We see the founders’ fears realized when President Trump refers to the military as “my generals.” We see it again when a largely peaceful demonstration was violently ended by authorities to create a moment of political theater, rather than out of public safety concerns.

By refusing to follow orders to deploy to U.S. cities, members of the armed forces could actually be respecting, rather than undermining, the very reasons that ultimately ground the principle of civilian control in the first place. After all, the framers always intended it to be the people’s military rather than the president’s.

The risks for the military

The reasons for disobedience in this kind of case, however, would have to be even stronger, for there is also a long and important tradition of the U.S. military remaining separate from politics.

Political action by the military reduces public confidence in the military’s truthfulness, competence and trustworthiness.

Disobeying orders certainly brings with it that risk, because many of the president’s supporters would likely decry any soldier’s refusal to obey as a partisan stain on a nonpartisan institution.

Yet it’s not clear that there’s any way to avoid that stain if members of the U.S. armed forces were ordered back into U.S. cities. Not after National Guardsmen wearing camouflage and carrying loaded automatic weapons have drawn those weapons on obviously peaceful citizens. Not after a photo of soldiers guarding the Lincoln Memorial has raised questions about what or whom they are protecting. Not after citizens primarily engaged in peaceful protest have been subject to gas canisters and grenades containing rubber pellets.

So, if military members find themselves in a tragic situation in which some level of partisanship is unavoidable, they would then have to consider which course of action would tarnish the military and our nation more. Some people will likely view any refusal to follow presidential orders as hyper-partisan. After recent events, however, others would surely perceive the military’s presence not only as partisan, but as a declaration that the very people they’ve taken an oath to defend are to be regarded not as fellow citizens, but as enemies of the state.

Other risks, too

Unlike their civilian leaders, members of the military can’t just resign because they disagree with an order. If they disobey legal orders, troops risk demotion and jail time.

But there is nonetheless a long line of military heroes who take on a different kind of risk – having the moral courage not to follow immoral orders. While the effect of that disobedience would be greatest if it were to come from those at the top – say, generals – it could be powerful at any level of the chain of command.

After all, it was a junior officer who first exposed the widespread use of torture in the war on terror, and a even lower-ranking warrant officer who prevented even more innocent lives from being lost in the My Lai village massacre in Vietnam.

It is for that reason we often ask our students to imagine themselves in numerous different ethical situations, both real and imagined. In the world in which we find ourselves, however, one set of ethical questions may quickly become much more concrete for those already serving: Would you obey an order from a president – this president – to deploy to a U.S. city? What might it mean for the nation if you did? And what might it mean for American democracy if, in some circumstances, you were brave enough not to?

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.