Taiwan’s officials are anxious, and rightly so. Taiwan’s strategic dilemma is getting worse. Beijing is intensifying its pressure on Taiwan, with Chinese fighter jets and naval vessels testing the island’s defenses, while Chinese vessels are implicated in severing Taiwan’s undersea telecommunications cables. At the same time, Taipei faces increasing uncertainty in its relationship with its primary security partner, given President Trump’s previous negative remarks about Taiwan, and the potential for tariffs targeting semiconductors.

The combination of a new U.S. administration and a more assertive China presents Taiwan with a daunting new reality: it must adopt assertive measures to hedge against the risk that the current—or a future—U.S. administration might regard Taiwan’s challenges as a distant concern. Consequently, Taiwan finds itself in a position similar to Europe, compelled to reevaluate its relationship with its historical security patron at the same time that the challenge from its primary adversary intensifies.

In response, Taiwan is taking proactive steps. The government plans to boost its defense spending, is considering how to tackle the trade imbalance with the United States, and the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is committing to new investments in the American semiconductor industry. These measures aim to maintain favorable relations with the Trump administration, prevent potential trade disruptions, and secure continued U.S. security assistance.

However, the critical question remains: Are these steps sufficient?

Improved Resiliency, Lagging Defense

During a trip to Taiwan in mid-February, we spoke to officials about the island’s national resiliency and defense efforts. Taiwan is taking steps to ensure that its government, economy, and society can withstand a range of threats, both man-made and natural, ranging from maritime blockades to natural disasters. A key driver is President Lai Ching-te’s Whole-of-Society Defense Resilience Committee, which is coordinating across the central government, between Taipei and local governments, and with civil society groups and private industry.

While these efforts are still embryonic, Taiwan now has an institutional framework that positions it to drive future results. It will be important to see how Taiwan tackles pressing risks, such as its reliance on imported energy, the vulnerability of the subsea cables linking Taiwan’s telecommunications to the world, the sufficiency of food and resource stockpiles, and the robustness of its cyber defenses in the face of unrelenting attacks from Chinese hackers.

Taiwan is taking steps to ensure that its government, economy, and society can withstand a range of threats, both man-made and natural, ranging from maritime blockades to natural disasters.

On national defense, progress is unsteady. Despite repeated criticisms within Taiwan and from its external partners like the United States that it needs to do dramatically more to improve its defense capabilities, Taiwan still spends a mere 2.45 percent of GDP on its military. President Lai has recently pledged to get this number above 3 percent of GDP. But many in Washington consider this inadequate, given the threat that the island faces. President Trump’s nominee for Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Elbridge Colby, stated during his confirmation hearing that “[Taiwan] should be more like 10 percent, or at least something in that ballpark.”

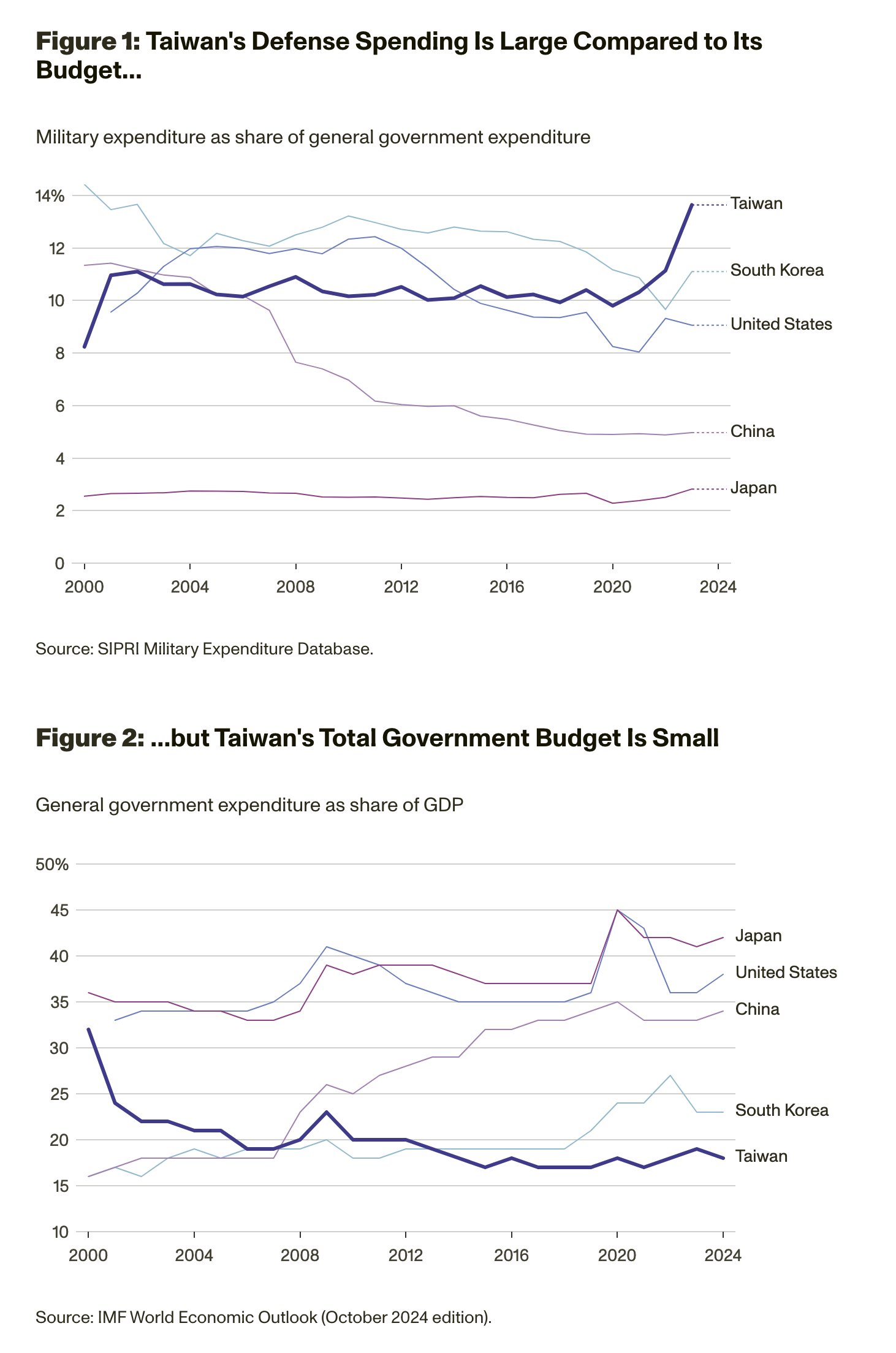

Taipei might argue that its defense budget is large as a share of the total government budget (Figures 1–2), and while this is true, it’s important to note that Beijing just announced an annual defense spending increase of 7.2 percent—equal in value to roughly 80 percent of Taiwan’s entire annual defense budget—even though China’s government revenues were flat last year.

In Search of a Trade and Investment Deal with Washington

In Search of a Trade and Investment Deal with Washington

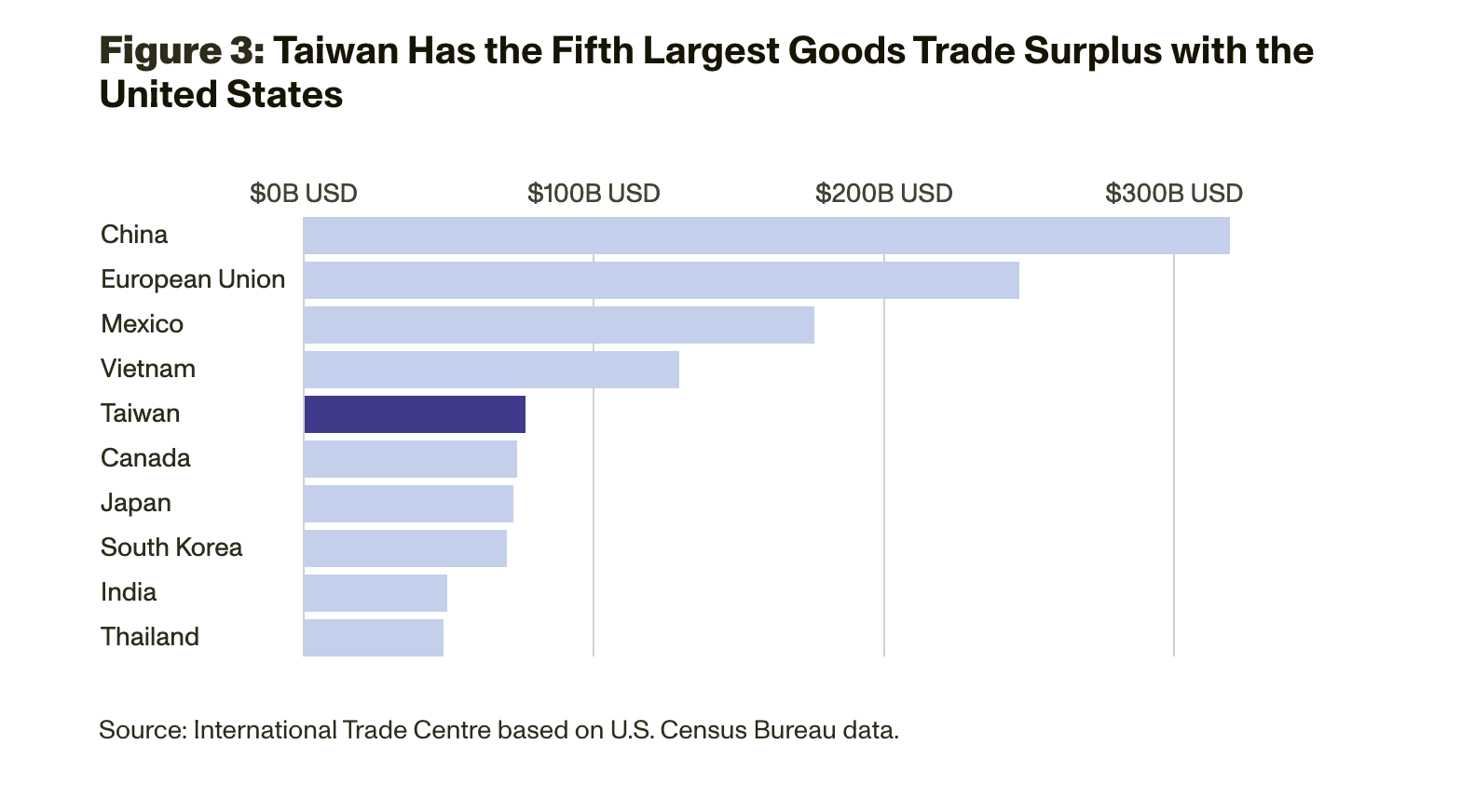

Taiwan’s trade surplus with the United States totaled $76 billion last year, the 5th largest among U.S. trading partners (Figure 3). Taiwan exported $119 billion in goods to the United States—mostly semiconductors and electronics—but imported only $42 billion. That means Taiwan would need to double its U.S. imports to bridge the gap, a tall order.

Like many governments facing the threat of new U.S. tariffs, Taipei is examining what deal it could offer the Trump administration, but the stakes are higher for Taiwan given the importance of U.S. security collaboration. Some of the key goods Taiwan does or could import from the United States contribute to its national defense and resiliency efforts, such as oil, liquified natural gas, coal, or electric generators for power plants. Taiwan also has existing relationships with major U.S. tech firms, which could be boosted.

Like many governments facing the threat of new U.S. tariffs, Taipei is examining what deal it could offer the Trump administration, but the stakes are higher for Taiwan given the importance of U.S. security collaboration. Some of the key goods Taiwan does or could import from the United States contribute to its national defense and resiliency efforts, such as oil, liquified natural gas, coal, or electric generators for power plants. Taiwan also has existing relationships with major U.S. tech firms, which could be boosted.

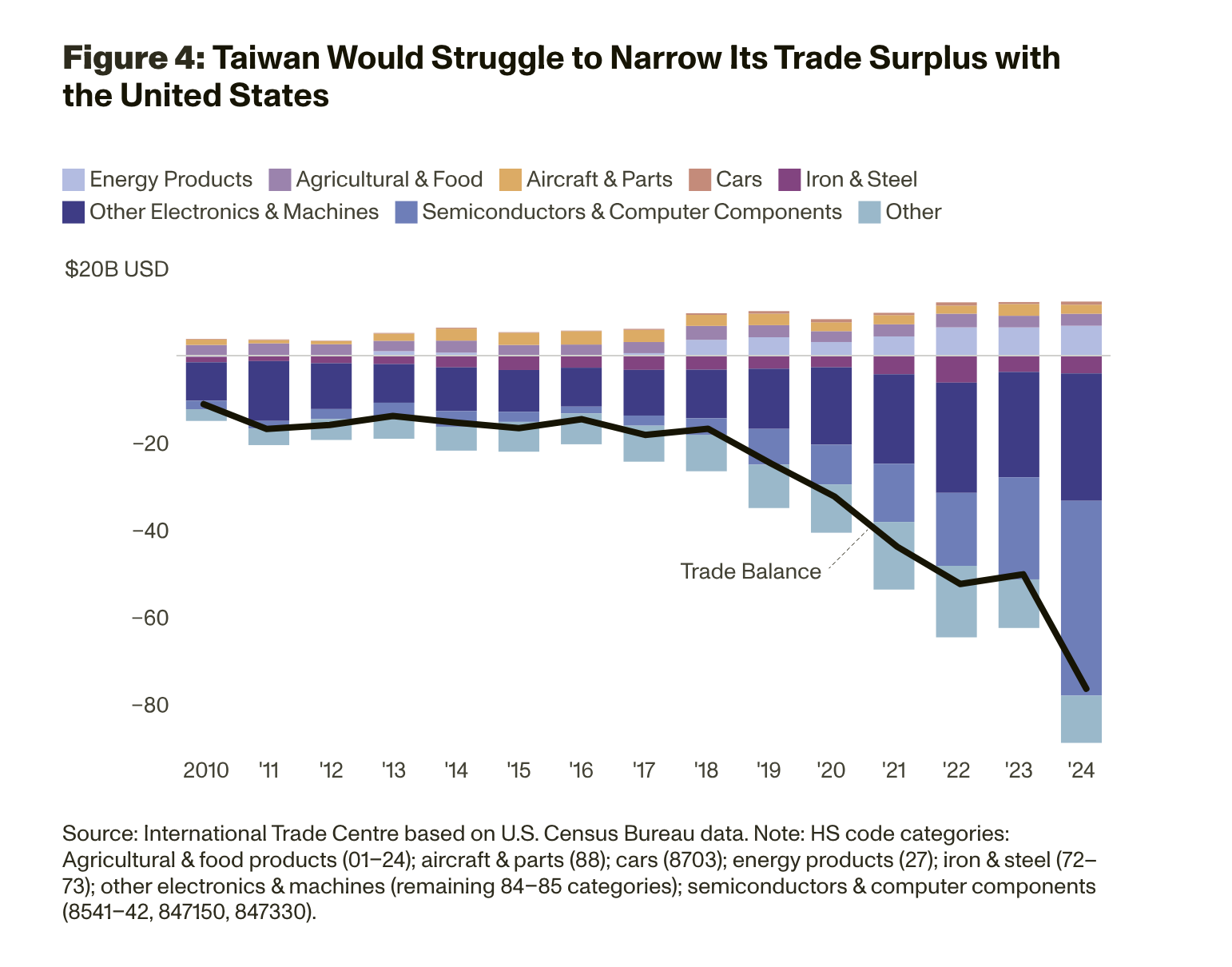

Semiconductors are likely to remain the key issue, however. Semiconductors and computer components that contain advanced chips accounted for nearly 60 percent of the U.S. goods trade deficit with Taiwan last year (Figure 4). There’s likely no way to substantially reduce the trade deficit as long as Taiwan-based semiconductor production remains dominant, especially given surging demand for advanced chips to power artificial intelligence data centers.

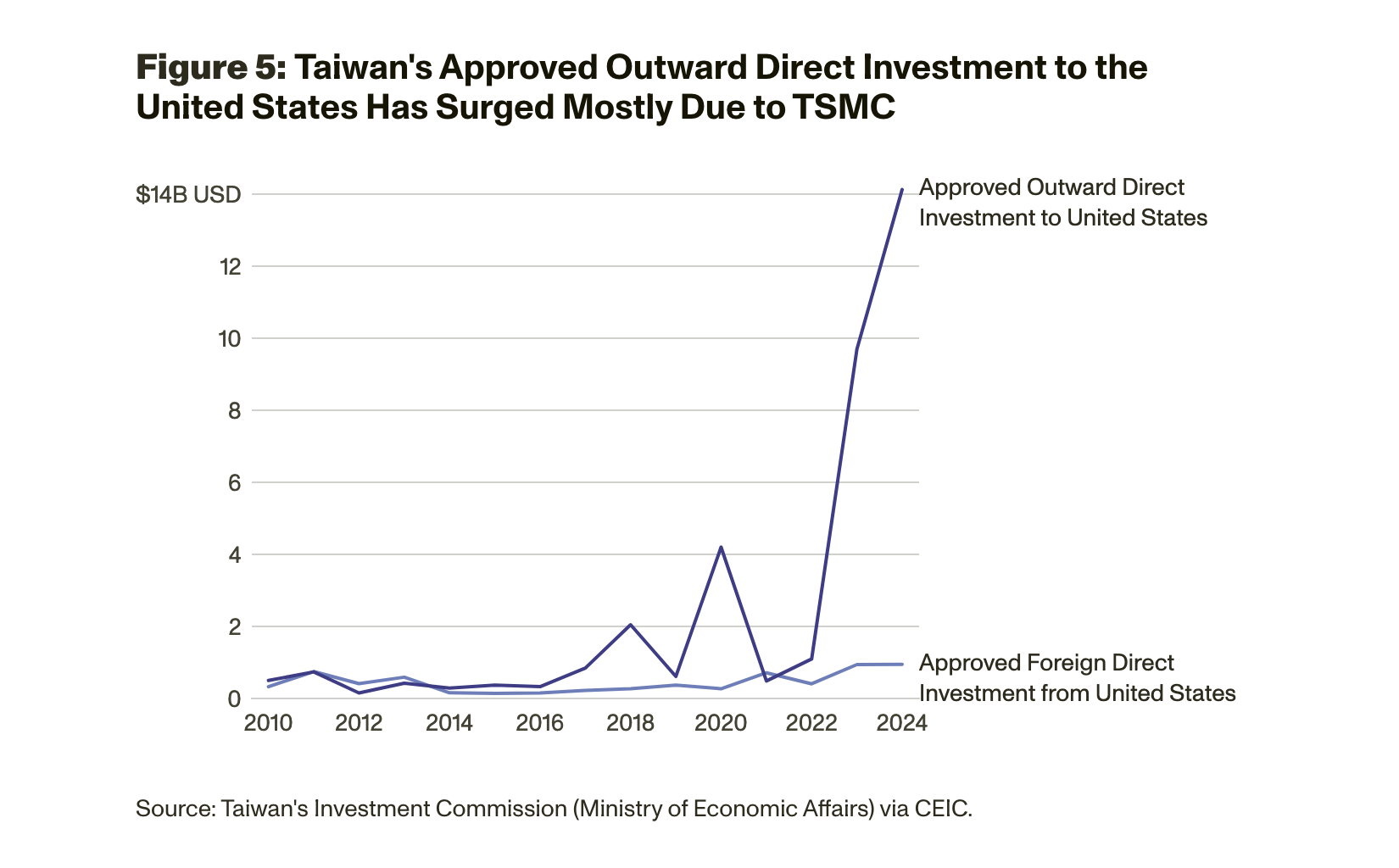

TSMC has already started to produce advanced chips in Arizona. The company’s U.S. investments likely account for most of the surge in Taiwan’s outward direct investment to the United States (Figure 5). As of last year, nearly 90 percent of Taiwan’s approved investment to the United States was in electronic components (semiconductors). But Washington wants more leading-edge chip production in the United States, even though this is unpopular among Taiwan’s public.

TSMC has already started to produce advanced chips in Arizona. The company’s U.S. investments likely account for most of the surge in Taiwan’s outward direct investment to the United States (Figure 5). As of last year, nearly 90 percent of Taiwan’s approved investment to the United States was in electronic components (semiconductors). But Washington wants more leading-edge chip production in the United States, even though this is unpopular among Taiwan’s public.

TSMC appears willing to comply, with planned new investments of $100 billion in the United States in the coming years, which Trump highlighted as a success in his recent speech to Congress. Given the composition of trade, such investments might be the most Taiwan could plausibly do to reduce the bilateral trade deficit in the medium term. Washington also reportedly wants TSMC to invest in and manage Intel’s fledgling semiconductor foundry business, even though TSMC doesn’t appear interested on commercial grounds.

TSMC appears willing to comply, with planned new investments of $100 billion in the United States in the coming years, which Trump highlighted as a success in his recent speech to Congress. Given the composition of trade, such investments might be the most Taiwan could plausibly do to reduce the bilateral trade deficit in the medium term. Washington also reportedly wants TSMC to invest in and manage Intel’s fledgling semiconductor foundry business, even though TSMC doesn’t appear interested on commercial grounds.

President Trump has threatened to impose at least 25 percent tariffs on semiconductors, and it’s unclear whether TSMC’s announced U.S. investments could blunt the threat of U.S. tariffs. The impact of the tariffs on TSMC would be manageable, as its customers are unlikely to find alternative suppliers. But for other Taiwan semiconductor firms producing legacy nodes, such as UMC, the tariffs would hurt, especially if U.S. tariffs on Taiwan’s chips were equal to or even slightly below those on Chinese chips. China’s production of all but the most advanced chips is rapidly expanding supported by Beijing’s industrial policies.

Further complicating Taipei’s playbook are three unique challenges. First, Taipei doesn’t have formal diplomatic relations with Washington, which severely limits the ability of the Taiwan government to directly interact with the Trump administration and President Trump himself. While talks with U.S. trade representatives are possible, such channels are substantially less effective than direct dealings with the President. Second, Taiwan knows that any U.S.-Taiwan trade deal could trigger retaliation from China. Third, Taipei believes that any economic talks with the Trump administration could be subordinated to, and maybe depend on, Washington’s talks with China.

Further complicating Taiwan’s calculus are the fast-moving shifts in U.S. relations with Russia and Ukraine. While Taipei has tied the fate of Ukraine to its own security challenges since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, such concerns were largely speculative and somewhat abstract. Now, however the Trump administration’s warming ties with Moscow, its willingness to negotiate Ukraine’s fate on its behalf, and Trump’s attacks on Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy have unnerved many in Taiwan who see parallels with their own precarious situation.

Taiwan’s Fate Is Its Own

Amid this geopolitical uncertainty, at least one thing is clear: Taiwan cannot use the same playbook it has over the past decade. China’s military has grown far too powerful, while the United States is in the midst of a historical re-think of its overseas security commitments.

All of this leads to one inescapable conclusion: Taiwan must do more for its own defense and resiliency, and fast. This should include doubling down on President Lai’s resiliency efforts, with a dramatic ramping up of energy, food, and potable water stockpiles. Taiwan must also press ahead with building its communications resiliency, investing in secure and redundant networks—such as satellite-based backup systems and decentralized infrastructure—to ensure that the flow of information remains uninterrupted even under duress. Bolstering civil defense programs through training, clear crisis protocols, and public awareness campaigns will further strengthen Taiwan’s capacity to endure and recover from any form of coercion or blockade.

Taiwan’s divided parliament constrains the Lai administration’s room to maneuver on defense spending. While Lai has pledged to get defense spending up to 3 percent of GDP this year through a special budget, this would still require legislative approval, and so the path forward isn’t clear. The unfortunate reality is that the politics of national defense have become hyper-partisan, as evidenced by the recent debates over Taiwan’s indigenous submarine program and the debate on extending the duration of compulsory military service. Even among supporters of ramped-up defense spending, debates can arise over the specific focus of the budget—whether it should prioritize indigenous weapons development, foreign arms purchases, or bolstering personnel training and welfare.

While the realities of democratic partisanship are understandable, they now present a clear threat to Taiwan’s future prosperity and security.

These tensions are likely to prolong discussions in the legislature and complicate negotiations at precisely the time that Taiwan can least afford partisan feuding. While the realities of democratic partisanship are understandable, they now present a clear threat to Taiwan’s future prosperity and security.

President Lai will need to hammer through these limitations, either through coalition building, or brute force. Like his predecessor, Tsai Ing-wen, Lai is hesitant about directly appealing to the Taiwan people about the true nature of the threat they face, justifiably worried about the side-effects of a panicked population. Given the threats facing Taiwan, and the uncertainty it must now attach to its primary security backstop, it may be time to begin making the case more directly to the Taiwan people that their future faces growing uncertainty. Lai’s recent speech, in which he explicitly labeled China a “foreign hostile force,” suggests he may already be shifting toward a more direct and assertive approach.

As the current secretary general of Taiwan’s National Security Council recently stated, “Our own fate is controlled in our hands.” Ten years ago, such a statement may have come off as a platitude. Given the seismic events of the past several months, however, such sentiments are truer than ever.

– Jude Blanchette is the Distinguished Tang Chair in China Research and the inaugural director of the RAND China Research Center. Gerard DiPippo is the acting associate director of the RAND China Research Center and a senior international/defense researcher at RAND. Published courtesy of RAND.