Key Findings

- While the ultimate resolution of the war in Ukraine is still uncertain, the way in which the conflict ends will inform the lessons that Russia learns from the conflict and, by extension, the decisions that Russia makes about reconstituting its military.

- Many economic and demographic factors will play an influential role in shaping the reconstitution process, as will Russia’s relationships with its key partners, including China, Iran, Belarus, and North Korea.

- The consensus is that Russia will continue to emphasize mass, conscription, mobilization, and nuclear capabilities in its military. However, four alternative pathways to reconstitution merit consideration because Russia will likely implement a hybrid approach, and changes in military culture would have an enormous impact not just on the military but also on national security decisionmaking after the Ukraine conflict.

- Although the speed of reconstitution is a key variable for U.S. and allied planners, this research focuses instead on the nature of the reconstituted Russian military. RAND researchers explore factors shaping Russia’s decisions about how it will reconstitute its forces to suit the Kremlin’s future military objectives, particularly with respect to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

- A partially reconstituted Russian military will still pose a significant—and potentially more unpredictable—threat to U.S. and Western interests in the European theater, complicating U.S. and allied planning efforts.

The timing and nature of any resolution to the Russia-Ukraine war remain unclear. However, what is certain is that Russia will face a considerable challenge in reconstituting its forces once the fighting ends. The process of reconstitution will provide an opportunity for Russia’s leadership to make choices—perhaps different choices from those its predecessors made—about the design, organization, training, and equipping of Russia’s future force. Russia’s efforts to reconstitute its armed forces will not occur in a vacuum. Rather, they will be informed by the past reform attempts highlighted in the timeline in Figure 1.

The New Look Reforms

The New Look reforms were the most recent effort to transform the Russian armed forces, and the legacy of these reforms shapes Russian thinking on reconstitution today. Launched in October 2008 by Minister of Defense Anatoly Serdyukov, the New Look reforms heralded the most radical changes in the Russian military since the creation of the Red Army in 1918. They were largely driven by political leaders who recognized the need to fundamentally transform Soviet mass mobilization forces to fight modern wars.

The reforms were designed to address the most-glaring shortcomings of the Russo-Georgian War, including improving mobility and logistics, command and control, and the performance of the Russian aerospace forces, and to enhance the ability of the Russian armed forces to engage in noncontact warfare. The reforms entailed undertaking a renewed rearmament effort, modernizing equipment, professionalizing the Russian military, increasing the responsiveness of Russian conventional forces, and moving toward smaller and more-streamlined forces with improved readiness levels.

The New Look reforms were met with criticism and fierce opposition within both military and civilian circles. A combination of mistrust, conflicting interests of political elites and the military, and insufficient funding limited their implementation. However, RAND researchers’ analysis suggests that the New Look reforms continue to influence Russian thinking about military reconstitution.

Research Approach: Four Potential Pathways for Reconstitution

RAND researchers identified a variety of approaches that Russia might take to reconstitute its military. They reviewed primary and secondary sources in Russian and English on historical defense reforms in Russia; the performance of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine; and military reconstitution, including official statements by Russian officials, Russian military scholarship, Western analyses of Russian military strategy and the war in Ukraine, and Russian and Western media sources.

To understand regional perspectives on Russian military reconstitution and potential reconstitution pathways, RAND researchers conducted discussions with experts on Russia, including researchers at think tanks, intelligence and defense officials, and government advisers in Poland, Estonia, Lithuania, and Sweden, and NATO officials and analysts. Synthesizing these inputs, the researchers identified four potential pathways, each representing a different approach to reconstitution that Russia might take.

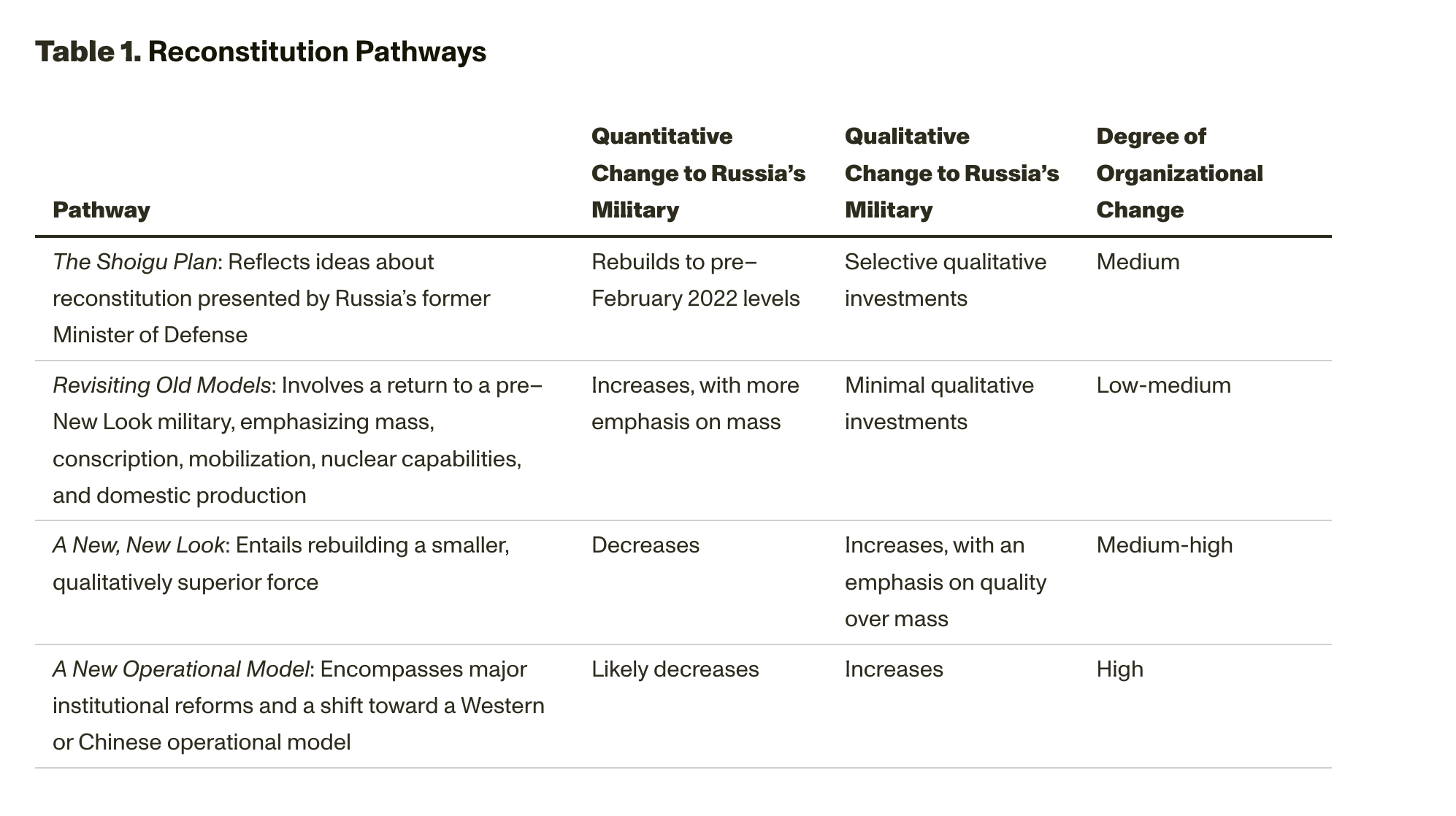

Each pathway represents a conceptual model that outlines the general characteristics of the Russian defense establishment and Russia’s future force. Each pathway is based on an overarching theme describing Russia’s general orientation and objectives, including whether it pursues qualitative (e.g., investments in advanced technologies) or quantitative (e.g., increases in force size) investments. In some cases, those objectives might be focused on returning to familiar operational models, whereas others portend major overhauls that would require significant organizational and institutional changes. The pathways are not mutually exclusive; Moscow’s reconstitutions efforts will likely combine elements from each (see Figure 2).

For each pathway, RAND researchers assessed how political, economic, demographic, technical, and foreign relations considerations may either enable or constrain reconstitution efforts.

RAND researchers also identified vulnerabilities associated with each pathway and considered how Russian decisionmaking on reconstitution may influence U.S. and NATO planning and force posture.

In assessing each pathway, they applied a uniform set of assumptions:

- Russia’s war in Ukraine has concluded.

- Russia’s leadership holds similar objectives and perceptions as it does under the Putin regime, even if Putin is no longer in power.

- Russian leadership’s perceptions of the United States and NATO remain the same.

- Russia continues to maintain its relations with key partners, such as China, Iran, Belarus, and North Korea (although Russia may seek to deepen these partnerships to achieve its objectives).

- Demographic and population trends continue along their current trajectories.

- There is no major popular revolt against Russia’s leadership.

- Russia maintains its current regional claims.

Reconstitution Pathway 1: The Shoigu Plan

Russia rebuilds its armed forces beyond their pre– February 2022 end strength, seeking to increase overall numbers based on new threats that have emerged since the beginning of the Ukraine war (e.g., the admittance of Finland and Sweden to NATO). Reconstitution efforts focus on the Russian Army, which has suffered considerable losses in Ukraine. Russia pursues selective qualitative investments, likely requiring changes in defense procurement strategies—in particular, increasingly looking beyond Russia to source certain technologies.

The argument for this pathway. Russia’s failures in Ukraine were due not to structural flaws but rather to poor leadership in the context of high-intensity conflict in a contested environment. Russia would make selective qualitative investments to remedy these deficiencies.

Can Russia make it work? Not all Russia experts believe that Russia can successfully implement The Shoigu Plan. Some regional observers that RAND researchers spoke with characterized it as “just paperwork,” neither realistic nor doable, and believe that Russia’s leadership is aware of the plan’s pitfalls. Others view quantitative increases as theoretically possible but see the plan’s qualitative investments as more challenging.

There are also conflicting perspectives on the country’s defense industrial capacity. Some believe that Russia can achieve the goals of The Shoigu Plan, at least in quantitative terms. The state has shifted financial resources toward the defense sector, and the defense sector can compete for labor because it can afford to increase wages and offer other incentives.

However, other experts that RAND researchers spoke with note that Russia faces labor, technology, and supply chain constraints, and its scientific capital and skill base have been in long-term decline. Russian civilians may not be willing to support the sustained investments in defense that the plan demands. In addition, increased industrial output does not guarantee increased defense productivity. Corruption affects the productivity of the defense industry, and increases in the defense budget translate into increased opportunities for corruption.

Influence of foreign partners. Russia’s relations with foreign partners will also shape the implementation of The Shoigu Plan. Iran has given the Russian armed forces drones that have had a catastrophic impact on the battlefield in Ukraine. It is unclear what North Korea could provide to Russia beyond stocks of Soviet-era munitions, although it has recently sent troops to support Russia’s war effort in Ukraine. Economically and technologically, North Korea is not in a position to give Russia the capabilities it may need to succeed under The Shoigu Plan.

Reconstitution Pathway 2: Revisiting Old Models

Russia returns to a pre–New Look military model. It emphasizes a mass, mechanized, attritionbased military that relies heavily on conscription and mobilization. Minimal qualitative investments are made, although a key element of this pathway is a heavier reliance on and investment in Russia’s nuclear deterrent. Russia relies primarily on technology it can produce domestically, making up for any technological gaps through quantity or asymmetry rather than sourcing advanced technologies from its allies.

The argument for this pathway. In many respects, the Russian military reverted to this model by necessity during its war in Ukraine, including by relying on older systems, overwhelming firepower, and mass.

Can Russia make it work? Revisiting Old Models may represent a more feasible pathway for Russia to pursue. As one expert observed in discussions with RAND researchers, Russia is “quantity-oriented and commander-centric.”

The importance of continuity in operational thinking in Russia would make a return to older operational models more likely. As one expert noted to RAND researchers, Russia will likely “bet on quantity, not quality.” Russian military decisionmakers may believe that they can “[turn] quantity into quality,” another expert noted.

The Revisiting Old Models pathway includes a greater emphasis on Russian nuclear forces, which would be enabled by the self-sufficiency of Rosatom, the state’s nuclear corporation. Rosatom is vertically integrated and oversees the entire production cycle from uranium mining to enrichment for nuclear fuel production and nuclear weapons. Russia’s nuclear industry is a kind of generator of high technologies that can be transferred to other sectors.

Influence of foreign partners. Russia’s foreign partnerships would support an approach that emphasizes quantitative increases over qualitative improvements. In particular, the country’s close partnership with Belarus will translate into quantitative advantages by augmenting Russian defense industrial production and providing a potential source of additional personnel.

This pathway may also reflect Putin’s own preferences for postwar reconstitution. The outcome of the war is a personal project for Putin. As one official in a NATO member state explained to RAND researchers, “He’s willing to take more risks, but he’s not willing to make big changes. [As a result, Russia] will rely on mass. Because Russia doesn’t have time, it’ll rely on what it has and what it knows, which is mass.”

Reconstitution Pathway 3: A New, New Look

Russia emphasizes qualitative investments instead of mass—the inverse of Revisiting Old Models. Russia rebuilds a smaller, yet qualitatively superior, force and pursues major personnel reforms. Russia prioritizes the development and use of asymmetric capabilities, Russian intelligence, security, and military special services; private military companies and other irregular formations are used more strategically and become better integrated with the armed forces.

The argument for this pathway. A New, New Look represents, in many respects, the inverse of Pathway 2 (Revisiting Old Models). This pathway would emphasize qualitative investments in lieu of an emphasis on mass. It would consist of reforms similar to those undertaken at the outset of the original New Look reforms, with a focus on those areas that were less successful (e.g., personnel reforms) or not as well-resourced (e.g., non-contact capabilities) as originally intended.

Can Russia make it work? Russia’s long-standing preference to rely on mass will make the country’s leadership less inclined to opt for this pathway. However, there may be efforts to adopt this model within discrete parts of the Russian armed forces by creating what experts referred to as “islands of professionalization.”

Russia’s ability to reconstitute by making qualitative improvements, thereby reducing the armed forces’ reliance on mass, will depend on the country’s ability to obtain and operationalize high-tech capabilities.

Role of technological capacity. The Ukraine war has demonstrated to Russia the superiority of Western technology, even though Ukrainian forces are fighting with older Western equipment. Russia is aware of the comparative strengths of Western capabilities, which could influence Russian leaders to take the A New, New Look pathway. Experts cautioned that it will be difficult for Russia to make qualitative improvements across the armed forces: Russia has historically struggled to maintain technical skills within the ranks of the military. Since the beginning of the Ukraine war, technical experts have left Russia en masse, and the existing workforce of technologists in the Russian military-industrial complex is continuing to age. As sanctions continue, moreover, the country’s ability to import needed components, such as microchips, will serve as a constraint.

Russia’s ability to reconstitute by making qualitative improvements will depend on the country’s ability to obtain and operationalize high-tech capabilities.

Reconstitution Pathway 4: A New Operational Model

Russia implements major institutional reforms within the defense establishment. To remain strategically competitive and relevant, the Russian armed forces are rebuilt in accordance with a new operational model that may adapt elements of existing models, such as the U.S. and Western model or the Chinese model. Russia pursues select qualitative investments. Russia seeks outside expertise to improve its operational art and tactics and leverages key external relationships to support the acquisition of new technologies and development of new strategic partnerships.

The argument for this pathway. The Soviet or Russian operational model is no longer viable, a fact highlighted by the Russian armed forces’ poor performance in Ukraine. This pathway would be an admission that the New Look reforms, as implemented, and the current Russian operational model did not work in Ukraine. Rather, Russian defense institutions and strategy need to be rebuilt from the ground up to meet the demands of modern warfare.

Can Russia make it work? To remain strategically competitive and relevant, the Russian armed forces would build a new operational model or adapt elements of other existing models (e.g., U.S. and Western or Chinese models). This pathway could emerge out of the theorizing of influential Russian military thinkers on the nature of future conflict and the necessary structure of the Russian armed forces, leading Russia’s leadership to consider implementing more-radical changes.

But the political and strategic cultures of today’s Russia make adoption of a new operational model unlikely, particularly one that takes a mission command approach and relies on the initiative of those at lower echelons. Russian political and strategic cultures disincentivize military officials from making decisions and taking initiative absent explicit orders from their superiors. Under this system, defined by “negative selection,” according to experts that RAND researchers spoke with, excellence is punishable because it may lead to disruption and feed criticism of the system.

If ground force commanders in the Ukraine war, who were forced to take initiative during combat, move up in the Russian defense establishment, a shift to an operational model centered on mission command might be more feasible. But Russia is unlikely to change the way its armed forces fight wars.

Influence of foreign partners. Russia would seek outside expertise to improve its operations and tactics and would leverage key external relationships (especially with Iran, North Korea, and China) to support the acquisition of new technologies and strategic partnerships. But there would be substantial constraints on Russia’s ability to adopt a Chinese-style operational model. The limits of China’s support for Russia have been clear throughout the war in Ukraine. Putin has described a “no limits” relationship, but in practical terms, sensitivities abound, including differing risk tolerances and sensitivities regarding the relative status of Russia in the bilateral relationship. Moreover, Russia may decide that it can and should reform on the basis of its own traditions rather than create dependencies on others.

A New Operational Model would be an admission that the New Look reforms, as implemented, and the current Russian operational model did not work in Ukraine.

Summary Assessment of Potential Reconstruction Pathways

Table 1 summarizes the reconstitution pathways considered in the RAND analysis, including an assessment of the degree of organizational change that would be required to implement the pathway.

Implications

Implications

RAND researchers’ analysis of these reconstitution pathways led to the following insights:

- The termination of the war in Ukraine will inform the lessons that Russia learns from the conflict and the decisions that its leaders make, not only about reconstitution but also about Russia’s national security and the country’s role in the international order more broadly. The lessons that Russia learns from the conflict may be counterintuitive, however, and they may not be the same lessons that the United States and its allies glean from the war. Russia has historically been willing to accept high casualties among its military forces, and early failures in the initial stages of the Ukraine war have not led to widespread calls for radical transformation within Russia.

- Russia’s relationships with its key partners—notably China, but also Iran, Belarus, and North Korea—will be particularly influential in shaping the reconstitution process and Russia’s postwar reality. Of this group, China will remain the most important because the war in Ukraine has magnified Russia’s dependency on China. China, which has a lower tolerance for risk and instability than Russia, cannot afford to have Russia lose the war in Ukraine, but it is not likely to sacrifice its own economic and geopolitical goals to prop up the Russian military.

- Russia’s reliance on a wartime economy will create path dependencies. The structural transformation of the Russian economy to support the war in Ukraine will have far-reaching impacts. The Russian defense industrial base has become dependent on government spending—a knot that will be difficult to loosen when the war eventually ends. Russia’s leaders could decide to pursue the permanent militarization of the economy even after the war concludes.

- A focus on not just the speed of reconstitution but also the nature of reconstitution is necessary to provide a full picture of the likely features of Russia’s future force. However, although U.S. regional allies are closely tracking the reconstitution issue, the conversation among Russia’s neighbors about Russia’s military reconstitution focuses on predicting the speed of reconstitution efforts.

- Even if Russia falls shorts of its objectives for reconstituting its armed forces, it will still pose a significant threat to U.S. and Western interests in the European theater. As Russia seeks to reconstitute its military to counter threats along its periphery, its focus on mass, firepower, and defensive systems will greatly stress NATO forces. In this respect, several elements of Russia’s military reconstitution that look like retrograde actions, such as decisions to lean more heavily on capabilities and systems that have not been favored in the past, may actually make it more difficult for the United States and its allies to contend with a partially reconstituted Russian military: Russia may therefore pose a more unpredictable threat.

– Michelle Grisé, Mark Cozad, Anna M. Dowd, John Kennedy, Marta Kepe, Clara de Lataillade, Krystyna Marcinek, David Woodworth Published courtesy of RAND.