India is heading to the polls in the world’s biggest democratic election and a number of different figures could emerge as India’s next prime minister in May.

The incumbent, Narendra Modi, and his main opponent, the Congress Party president, Rahul Gandhi, are obviously the most likely candidates. But if they both fail to gain sufficient seats to form a government, they could be displaced from within their own parties. It is also possible that, in a fragmented parliament, another politician from one of the regional parties could stitch together a coalition.

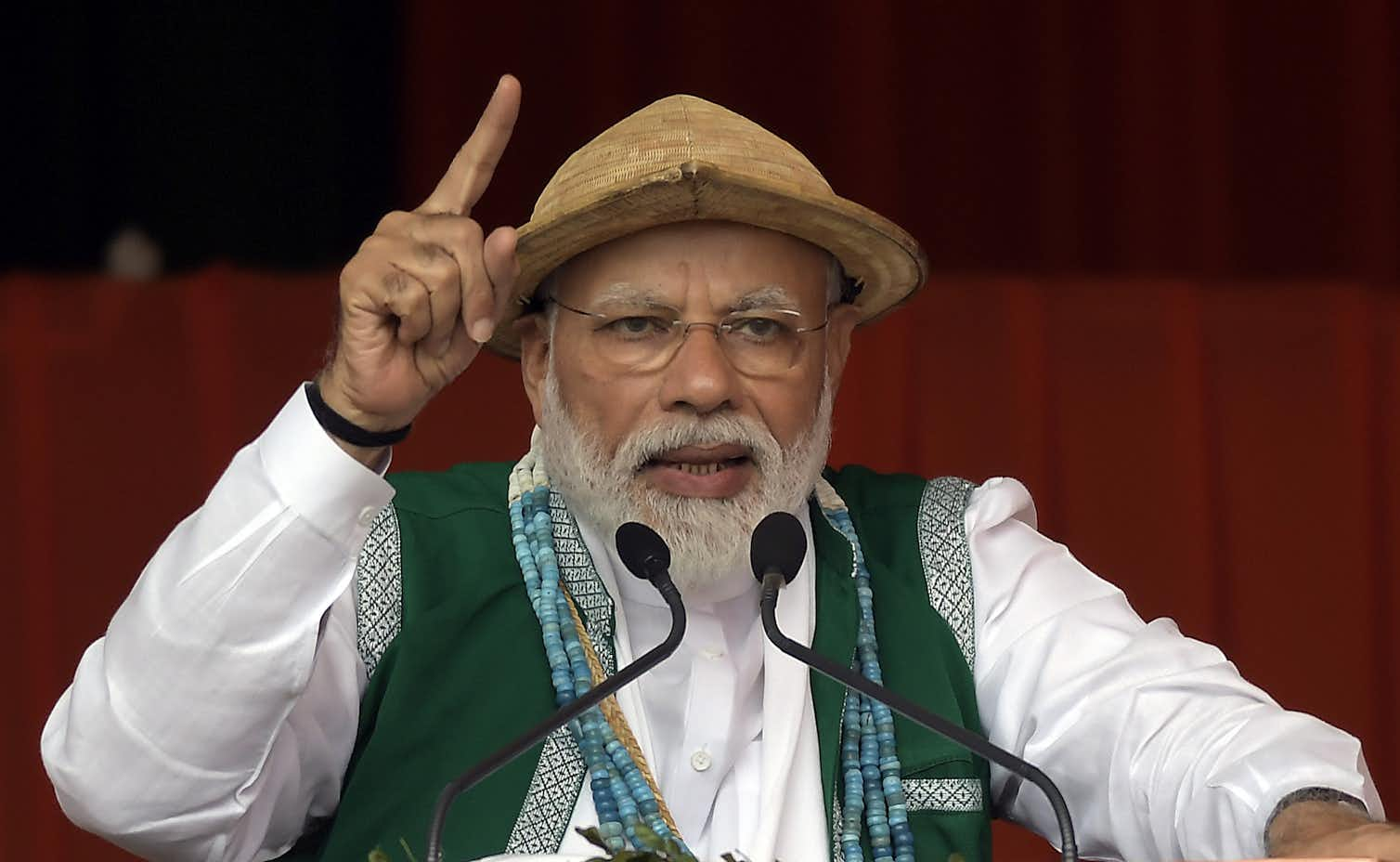

In 2014, the electorate delivered Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) the first absolute majority gained by any party since 1984. Tired of a Congress Party-led government mired in corruption scandals and rampant inflation, voters embraced Modi’s promise to clean up politics, cut red tape, create jobs, and restore confidence. They also embraced Modi himself, despite his controversial past as a Hindu nationalist firebrand, responding positively to his claim that he had matured into a selfless vikas purush (“development man”).

But the Modi government’s failure to deliver what it promised has tarnished that image. Anti-corruption efforts have caused pain, with small businesses hit by the sudden decision in late 2016 to withdraw large denomination banknotes from circulation. Economic growth has flagged, and jobs are scarce.

Despite this, in February, a terrorist attack in disputed Kashmir and a retaliatory Indian air strike on Pakistan have made national security the salient election issue, handing Modi another chance to reinvent himself. In response, he has assumed the mantle of a chowkidar (“watchman”), asserting in a slick media campaign that in these troubled times, he and his supporters are best suited to defend India from its enemies both inside and outside the country.

The dynasty

Modi’s principal opponent, Gandhi, has been caught flatfooted by this shift. The scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, related to three of India’s former prime ministers, Gandhi is 20 years Modi’s junior, and ought to be more in tune with India’s youthful voters. But he struggled to connect with the electorate, including first time voters, in 2014, when his Congress Party secured just 44 out of 543 contestable parliamentary seats. Since then, he has also struggled to capitalise on the Modi government’s apparent failures to boost economic growth, create jobs, and address rural poverty.

In 2019, the Congress Party should nevertheless do better, if opinion polls and seat projections are any guide. Gandhi will be supported by his popular, if enigmatic, sister, Priyanka Gandhi Vadra. Her striking resemblance to her former prime minister grandmother, Indira Gandhi, appeals to some Congress voters, and her apparent savvy to party officials. She has not yet announced that she will stand for a seat, however, and the allegedly murky real estate dealings of her husband, Robert Vadra, makes her vulnerable to BJP attacks.

The Gandhis have considerable assets – instant name recognition and an established, nationwide party organisation – but also significant weaknesses. Rahul Gandhi’s abilities and commitment remain in doubt.

The Congress campaign has been often negative, summed up in its slogan “Chowkidar Chor Hai” (“The watchman is a thief”). And the fact that the Congress Party is still run by a dynasty – however distinguished – alienates some voters.

Powerbrokers and rivals

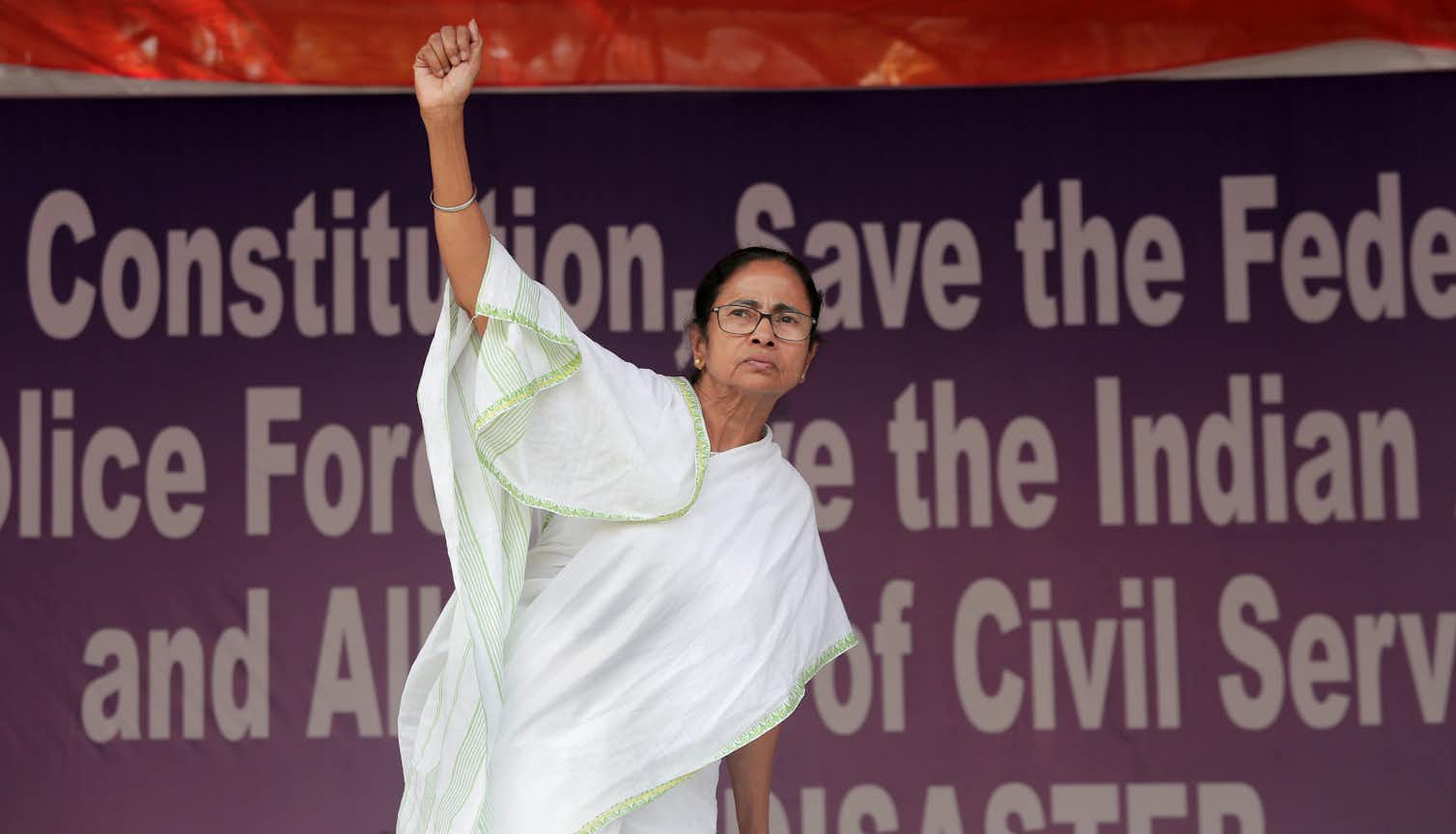

It is unlikely that either the BJP or the Congress Party will come close to winning a majority in parliament. To rule, they will need the support of a number of regional allies, especially from the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu, which account for almost half the seats. This may hand power to regional powerbrokers, such as West Bengal’s mercurial chief minister, Mamata Banerjee, who will be able to direct their MPs to support one or other leader.

These powerbrokers could deliver either main party into government, albeit it at a price, in terms of both cabinet positions and modified policies. Alternatively – in an admittedly improbable scenario – they could even come together to form a Mahagathbandhan or “grand alliance”, with one of their number as prime minister, should either Modi or Gandhi fail.

It is also possible that the BJP could emerge as the largest party and in a position to form government, but with a disappointingly low number of seats, leading to a challenge to Modi’s position. So far, he has been fortunate that some of his potential rivals within the BJP, such as external affairs minister Sushma Swaraj, have been unwell or unwilling to challenge his leadership.

Recently, however, the names of potential successors have been canvassed more openly, including that of roads and railway minister Nitin Gadkari. Should the BJP lose more than a 100 seats, some speculate that an alternative leader, with a less autocratic style better suited to managing a delicate coalition, could well be sought out by the party.

Ian Hall, Deputy Director (Research), Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.