As the protests in Hong Kong enter their eleventh straight week, it’s not uncommon to see teenagers dressed in full battle gear. When I was in Hong Kong in mid August, I encountered a group of young people, including some who looked as young as 14, on their way to a late-night protest wearing face masks and protective gear. I saw them behave in a way that suggested they didn’t care about the consequences of protesting.

Many of the young people protesting in Hong Kong talk online about feeling they have little to lose. For many, this seems like their generation’s chance to fight the overwhelming influence of China on Hong Kong’s way of life.

Demonstrators continue to impress the world with their enormous mobilisation. Organisers estimated 1.7m people attended a peaceful mass rally on August 18, which made it the second largest in the Special Administrative Region’s history. Turnout wasn’t affected by torrential rain, or the severe limitations authorities placed on protest sites and routes.

The latest peaceful protests keep up pressure on the Hong Kong and Beijing governments, which are still hoping the movement will fizzle out, as the previous protests of the Umbrella Movement did back in 2014.

It’s possible the authorities were waiting for violent behaviour from some of the protesters’ more radical factions to give them a pretext to deploy drastic police measures, or even an intervention by forces from mainland China. Nothing like this happened.

Instead, calls for a calm and peaceful protest on LIHKG, one of the main online platforms used by the protesters to organise and communicate, suggest that the leaderless movement is capable of moderating between its different factions.

The previous week was one of the most dramatic of the protests so far. Activists defied restrictions and bans on demonstrations on the weekend of August 10 and 11, opting for rallies and events at several places across the territory.

On that Sunday, I was in Hong Kong and observed a protest march in Kowloon from Sham Shui Po to Cheung Sha Wan. It was very well attended by citizens from all ages and backgrounds, though young people wearing facemasks to disguise their identity were in the relative majority. The protest that afternoon was illegal, yet peaceful and well organised.

I saw the participants providing water and rubbish bags, and demonstrators making way for vehicles travelling on the roads. Onlookers and bystanders cheered protesters on and young vendors from South Asian ethnic-minority backgrounds handed out free soft drink cartons of lemon or chrysanthemum tea. After the march arrived at its end point, the Cheung Sha Wan MTR underground station, a group of young masked activists hid behind umbrellas and quickly assembled roadblocks. Within minutes, the police reacted by firing tear gas.

Tensions rising

It had already become clear that Hong Kong’s police had prepared an escalation of their counter measures. On that same Sunday, the police resorted to using tear gas inside MTR stations. They deployed undercover officers dressed as protesters to make arrests, which undermined the high level of trust among protesters, at least temporarily. It also emerged that a woman was shot that day with an apparent beanbag round at a parallel protest in Tsim Sha Tsui, causing a rupture of her right eye.

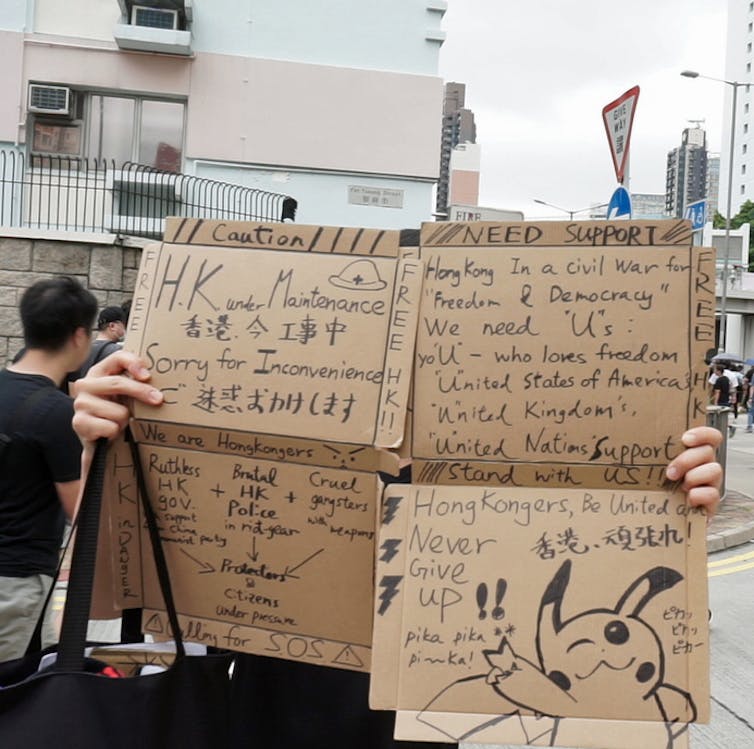

This new level of police violence was condemned by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet. Protesters reacted to the violence by escalating action further and staged mass sit-ins and blockages of the airport on the following two days which brought air travel to a standstill. The protesters achieved their goal of gaining significant international attention. I saw some speaking flawless English, handing out information pamphlets at major traffic hubs in the city, targeting overseas travellers and apologising for the inconvenience caused by the protests.

Yet there were clashes with the police and protesters did attack a mainland Chinese journalist who failed to show his press card, which tarnished the international image of the demonstration. This presented the movement with a major challenge as gaining international attention for the protests have been an important strategy from the very beginning. The idea is that international pressure will push the Hong Kong government to start engaging with the demonstrators and agree to their demands, which include the complete withdrawal of a controversial extradition bill and an independent inquiry into police behaviour.

The goal of the peaceful protests on August 18 was to regain international support. The Chinese authorities realised this and engaged in counter propaganda and mobilisation internationally, while at the same time trying to scare Hong Kongers with military drills a few kilometres beyond the border in Shenzhen.

Fearless

The most radical of the young protesters are unlikely to be deterred by threat of intervention from Chinese paramilitary forces. Many feel they have little to lose. Aged roughly between 14 and 20, these young people have realised that Hong Kong’s political and economic system is deeply unfair, and all odds are stacked against them. They don’t want to defend Hong Kong’s status quo. Many were fearless about the consequences of their actions, driven by anger over police brutality and government incompetence.

In the online forums used by the movement, protesters discuss ideas of a scorched-earth policy, by which they mean provoking an economic crash. Forum administrators have names roughly translated as “I want to die/burn with you” and slogans such as “if we burn, you burn with us” are frequent. One post from early July, about the storming of the Legislative Assembly building, had the title “We die together”.

This radical faction had their political awakening in the aftermath of the 2014 Umbrella Movement when activists, known as “localists”, called for direct actions to bring about change. Their hope was the fight against rapid economic and social integration with China, for real universal suffrage and autonomy or even independence for Hong Kong. But much of the leadership of the localist movement was either imprisoned or in exile, many young protesters now feel that their future is at stake.

The high price young activists have already paid, of arrest injury or both, during the protests reinforces their fearlessness. It’s unlikely that they will be satisfied with anything other than real change. On August 20, Hong Kong’s chief executive promised to create a “platform for dialogue” between the protesters and authorities. But it’s not clear yet whether the Hong Kong and Beijing governments are willing to give way, or whether they are prepared to further alienate an entire generation.![]()

Malte Phillipp Kaeding, Lecturer in International Politics, University of Surrey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.