Can an inheritance law lead to taller children? The answer is a qualified yes, according to new research from Binghamton University, State University of New York.

Md Shahadath Hossain, a fifth-year doctoral candidate, and Assistant Professor of Economics Plamen Nikolov recently published “Entitled to Property: Inheritance Laws, Female Bargaining, and Child Health in India,” with the IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

“The question is important because it shows the critical importance of how better parental care and parental investments can have an enormous influence on child height,” Nikolov said. “And we know from extensive economic research that height in early childhood is strongly predictive of cognitive ability, educational attainment, labor market outcomes and occupational choice in later life.”

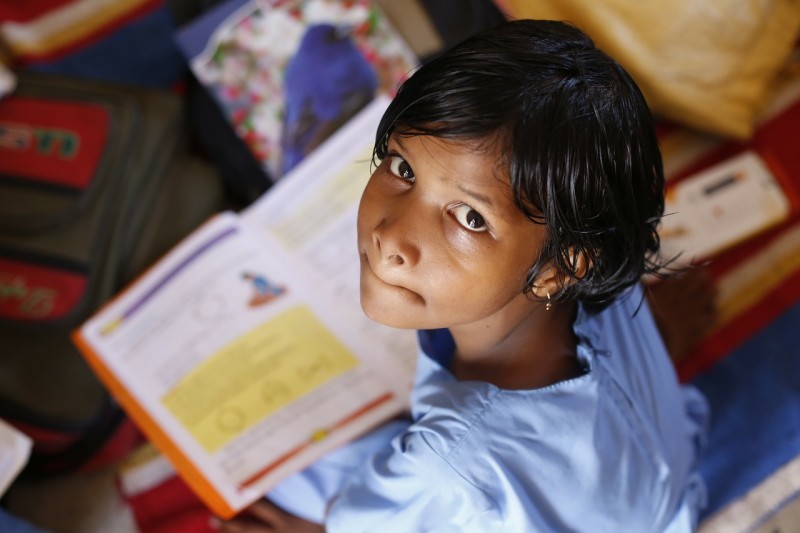

Indian children are extremely short, and not as a result of typical human height variation. They experience a phenomenon known as stunting, in which they don’t grow as much as they otherwise would, due to factors such as malnutrition. Stunting affects 31 percent of Indian children under the age of five, surpassing their counterparts in sub-Saharan Africa and accounting for parental wealth and education.

While biology and genetics drive many health outcomes, individual behaviors also play an important role, particularly with such characteristics as height. At a population level, better nutrition and parental care can contribute to taller children, Nikolov pointed out. In the case of patrilineal Hindu communities in India, a pregnant woman is likely to receive more family resources — such as nutritious foods, iron supplements, tetanus shots and prenatal checkups — if there is a possibility that she is carrying the family’s firstborn son.

Also at play is the non-unitary economic model of the household, in which partners tend to have unequal weight in decision-making due to power dynamics. The partner with more bargaining power — for example, from having more financial resources at their disposal — has more of a say in household decisions.

Men and women in a household also typically exhibit different economic preferences when it comes to extra resources. When women get an income boost, they often spend a higher portion on healthcare, better nutrition and education-related expenditures than men do, studies show.

Except for matrilineal tribal communities, Hindu populations in India traditionally pass ancestral property down the male line; this type of property, which goes back for up to four generations, is distinct from personal property, which can be allocated through wills and gifts to whomever the giver chooses. In 1956, the Hindu Succession Act Amendment (HSAA) enabled unmarried daughters to inherit ancestral property for the first time. This policy has led to a cascade of changes; women in states with the HSAA also tend to marry later and have fewer children, for example.

It also made an impact on child health and height — but only the health of some children.

Human capital

When you factor the HSAA into the non-unitary model of household economics, you find that women — newly empowered with their inheritance — have more of a voice in decision-making, the researchers found. Combined with the gender disparity in economic choices, that means more resources may end up spent on child health and parental care, from clinic visits to better nutrition and vaccinations.

That, in turn, can and does make children taller — if they’re first-born sons.

“The difference may be due to religious as well as cultural norms,” Nikolov explained. “Hinduism prescribes a patrilineal kinship system, meaning that aging parents live with their son, typically the eldest, and bequeath property. Also, Hindu religious texts stipulate that only a male heir performs certain post-death rituals, such as lighting the funeral pyre, taking the ashes to the Ganges River and organizing death anniversary ceremonies.”

Because of this, Indian society has a marked preference for the eldest son, which leads families to reduce the resources that they could otherwise spend on later-born children and daughters. Unless policies are put into place to counteract the social and economic forces behind son preference, Indian daughters may continue to receive less than their fair share, he said.

Despite this caveat, their research demonstrates that improving the economic status of women in a developing country can generate additional benefits in improving child health, which is an important marker for both better health and economic well-being later in life.

“In sum, policies that empower women can pay big dividends in terms of a country’s human capital and economic development,” Nikolov said. “Investing in women is not just the right thing to do; it’s also smart economics.”