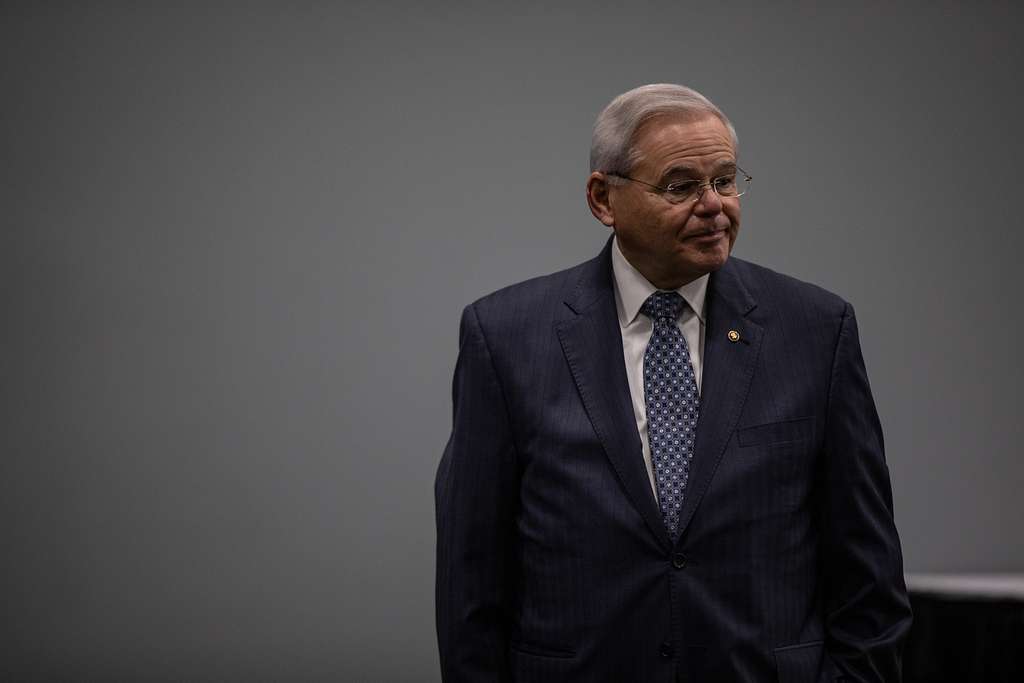

Allegations against Sen. Robert Menendez raise serious questions about the Egyptian government’s interference in U.S. interests.

On Sept. 22, Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) was indicted on three counts of conspiracy in relation to hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of bribes that he and his wife are alleged to have accepted in exchange for actions benefiting the government of Egypt. According to federal prosecutors in the Southern District of New York, between 2018 and 2022, Menendez allegedly abused his leadership and decision-making role in the U.S. foreign policy apparatus to approve deals in favor of the Egyptian regime, to discourage and block aid conditionality, and to share nonpublic information with Egyptian security and military officials at the expense of U.S security considerations.

So far, public attention in the U.S. has focused mostly on the absurdist details of the indictment—like the bars of gold allegedly gifted to Menendez as part of the corruption scheme, or the thousands of dollars of cash stuffed in the senator’s monogrammed jackets. And Beltway media coverage has zeroed in on the question of whether or not he will remain in office. In the hours and days since the public release of the indictment, a number of U.S. officials and lawmakers, including Democrats in New Jersey and in Congress, have called for his resignation.

But the indictment also raises separate, serious questions about the Egyptian government’s interference in American interests. Amid all the jokes about gold bars, commentators shouldn’t lose track of what these charges might mean for the future of U.S.-Egypt relations.

For decades, the United States’ approach to its relationship with Egypt has been shaped through the more than $50 billion in military and $30 billion in economic assistance it has provided, the extensive military training exercises it has arranged for, and the vast weapons sales it has approved—the product of a dated understanding that, without these promises, Egypt will not keep the peace with Israel. The Department of State says Egypt is a “valued U.S. partner in counterterrorism, anti-trafficking, and regional security operations.” But is Egypt truly the reliable security partner that the U.S. describes?

The Indictment

Put in the simplest terms, the indictment alleges that Menendez and his wife received hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of bribes—in the form of cash, gold bars, luxury vehicles, and payments toward a home mortgage, among other items of value—from three New Jersey businessmen, Wael Hana, Jose Uribe, and Fred Daibes. In exchange, according to the government, Menendez used his official position to protect and enrich the three men, as well as to benefit the government of Egypt. Menendez allegedly did so while serving as ranking member and later chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, a role that gave him consequential decision-making influence in key assistance, weapons, and diplomatic decisions. (Menendez’s wife was indicted alongside her husband, as well as Hana, Uribe, and Daibes.)

In early 2018, as the indictment tells it, Menendez’s now-wife, Nadine Arslanian, informed her friend Hana, who is Egyptian American, that she was dating the senator. In the months and years that followed, Arslanian and Hana would together introduce Menendez to Egyptian intelligence and military officials “in exchange for Menendez’s acts and breaches of duty to benefit the Government of Egypt, Hana, and others,” the government states.

The indictment details a series of acts to this effect, including one in which Menendez is alleged to have ghostwritten a letter for an Egyptian official on behalf of the government of Egypt to convince U.S. senators to release a hold on $300 million of U.S. assistance to Egypt. (As part of the assistance that Egypt receives from the United States, a portion is subject to release pending confirmation that Egypt has met certain human rights conditions.) In another incident, Menendez reportedly sought nonpublic information regarding the number and nationality of persons serving at the U.S. Embassy in Cairo; he then texted the information to Arslanian, who passed it on to Hana, who then sent it off to an Egyptian official. That same month, Hana allegedly hosted a dinner with Menendez during which Menendez shared nonpublic information about the U.S. provision of military assistance to Egypt.

But that’s not all. The indictment is stuffed with additional examples of Menendez allegedly receiving bribes and intervening in policy agenda items at the behest of Egyptian officials—including on human rights issues, foreign military sales, and the dispute with Ethiopia on allocation and access to the Nile River’s waters and its construction and filling of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. According to the indictment, Menendez would approve or remove holds on U.S. assistance and sales of military equipment and convey his consequential role in the decision to Hana, who would in turn inform Egyptian officials.

In exchange for these acts, the indictment states, Menendez and Arslanian were promised and then given payments, including from IS EG Halal, a New Jersey company operated by Hana with financial support from Daibes. The company, which the Egyptian government granted an exclusive monopoly on the certification of U.S. food exports in the halal market to Egypt, would provide a “revenue stream” from which Hana would make bribe payments. (While the indictment doesn’t note this, it’s worth flagging that in 2019, independent Egyptian media outlet Mada Masr uncovered the company’s ties to high-level security institutions in the Egyptian government.) When U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) officials contacted Egyptian authorities seeking a reconsideration of the monopoly enjoyed by IS EG Halal, Egyptian intelligence officials allegedly called on Menendez to counter the USDA’s objections, which Menendez did. (The indictment notes that while USDA officials did not accede to Menendez’s demands, IS EG Halal did keep its monopoly.)

Beyond the allegations related to the government of Egypt, Menendez is accused of having received bribes to take actions to disrupt a criminal case brought by the New Jersey attorney general involving associates of Uribe and a federal criminal prosecution brought by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of New Jersey against Daibes.

The defendants are all set to appear before federal court on Sept. 27. Menendez, for his part, has maintained his innocence, saying that prosecutors have “misrepresented the normal work of a congressional office.”

Egypt’s Record of Interference and Influence

Describing the U.S.-Egypt relationship, the Department of State website refers to a “century of diplomatic cooperation and friendship.” It details extensive U.S. assistance and investment in Egypt, alongside cooperation on regional disputes, trade, and climate; a “decades-long defense partnership”; and professional and academic exchange programs. Egypt is the second-largest recipient of U.S. foreign military financing after Israel. In the face of extensive evidence of serious human rights abuse, the U.S. has, at times, moderately critiqued Egypt’s record and conditioned a percentage of assistance on human rights conditions—a discussion that consumes the foreign policy apparatus on an annual basis. For a sitting senator and U.S. foreign policy leader with influence over this kind of strategic relationship to allegedly accept bribes and take actions at the behest of a foreign government, and possibly at the expense of U.S. interests, is incredible.

Yet this is not the first time that Egyptian government officials have improperly interfered in U.S. foreign policy. It’s not even the first time that Egyptian authorities have taken actions that explicitly go against U.S. interests.

In January 2022, for example, a New York man named Pierre Girgis was arrested after investigators uncovered that he had been operating “at the direction and control of multiple officials of the Egyptian government in an effort to further the interests of the Egyptian government in the United States,” without registering as a foreign agent. Among other things, the Justice Department alleged, Girgis had tracked and obtained information about peaceful dissidents in the United States, collected nonpublic information from law enforcement officials, coordinated meetings between U.S. and Egyptian law enforcement in the United States, and arranged for benefits for Egyptian officials visiting New York.

Egyptian authorities have become complicit in a growing number of incidents of transnational repression, illegally targeting Egyptian citizens on U.S. soil—often in reprisal for their political stances. Reporting from Politico in 2021 suggests that the head of the Egyptian General Intelligence Directorate lobbied U.S. targets to get a U.S. citizen arrested. In a report published in 2023, the Freedom Initiative documented tens of instances of surveillance on dissidents by Egyptian operatives at restaurants and public events in the United States, and death threats and defamation campaigns targeting U.S. citizens and permanent residents.

Even in the face of U.S. pleas and engagement, Egypt has arbitrarily arrested, tortured, and tried U.S. permanent residents and citizens—including Mustafa Kassem, who died after spending six years in Egyptian custody. And despite the growing instability that the country’s economic and human rights crisis contributes to, Egypt has continued to fail to deliver on equitable social and economic policy for its people, instead concentrating its resources and efforts in the building of vanity megaprojects and the silencing of dissenting voices through arrests and prosecutions.

When it comes to the war in Ukraine, the Egyptian government has claimed that it has attempted to remain “neutral,” though it has also taken actions against U.S. interests. In April of this year, Egypt ordered subordinates to produce up to 40,000 rockets to be covertly shipped to Russia. Though the plan was ultimately not executed, it was crafted at the height of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and despite U.S. leadership in the fight.

In his public statement, Menendez says: “I have … stood steadfast against dictators around the globe—whether they be in Iran, Cuba, Turkey, or elsewhere—fighting against the forces of appeasement and standing with those who stand for freedom and democracy.” Strangely, though, the senator doesn’t mention the country with whose dictatorial government he is alleged to have been collaborating.

Looking Ahead

Already, news coverage of the Menendez indictment has focused on the domestic implications—what it means for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the senator’s seat, and the laws and regulations governing transparency and foreign interference in U.S. democracy.

But this is also a critical moment to look carefully at the U.S.-Egypt relationship, what it delivers, and what it does not. At a minimum, Congress should move to immediately place a hold on the $235 million in conditional foreign military financing that was just approved by the Biden administration through a national security waiver exercised by Secretary of State Antony Blinken. (Under U.S. law, $320 million in assistance to Egypt is subject to human rights conditions; however, the secretary can waive these conditions for $235 million of that funding if in the U.S. national security interest.) Doing so will send a clear message that foreign interference of this nature, be it by Egypt or other countries, will not stand. If appropriate, targeted sanctions against the identified Egyptian officials proved to be complicit in this incredible act of corruption could become warranted down the line.

The indictment should make clear to the U.S. foreign policy apparatus what Egypt experts have been saying all along: Egyptian government officials act in their own self-interest, and U.S.-Egypt interests do not always align. U.S. support via statements, assistance, sales, and soft power cannot afford to be unconditional and compromising of U.S. interests and values—including human rights. Only if American policymakers are able to acknowledge this nuanced reality and take necessary action in response will the U.S.-Egypt relationship bear any meaningful and lasting fruit.

– Mai El-Sadany is a human rights lawyer with a focus on the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. She is currently the Executive Director of the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP), an organization dedicated to centering the insights and expertise of advocates from and in the MENA region in the policy discourse to foster transparent, accountable, and just societies. She is a member of the Working Group on Egypt.