On Oct. 30, 2023, reports began to circulate that Israel was missing from from the mapping services provided by Chinese tech companies Baidu and Alibaba, effectively signaling – or so some believed – that Beijing was siding with Hamas over Israel in the ongoing war.

Within hours, Chinese officials began to push back on that narrative, pointing out that the names do appear on the country’s official maps and that the maps offered by China’s tech companies had not changed at all since the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas. Indeed, the Chinese Foreign Ministry took the opportunity to go further, emphasizing that China was not taking sides in the conflict. Rather, Beijing said it respected both Israel’s right to self defense and the rights of the Palestinian people under international humanitarian law.

This assertion of balance and even-handedness should have come as a surprise to no one. It has been the bedrock of China’s strategic approach to the Middle East for more than a decade, during which time Beijing has sought to portray itself as a friend to all in the region and the enemy of none.

But the map episode underscores a problem Beijing faces over the current crisis. The polarization that has set in over this conflict – in both the Middle East itself and around the world – is making Beijing’s strategic approach to the Middle East increasingly difficult to sustain.

As a scholar who teaches classes on China’s foreign policy, I believe that the Israel-Hamas war is posing the sternest test yet of President Xi Jinping’s Middle East strategy – that to date has been centered around the concept of “balanced diplomacy.” Growing pro-Palestinian sentiment in China – and the country’s historic sympathies in the region – suggest that if Xi is forced off the impartiality road, he will side with the Palestinians over the Israelis.

But it is a choice Beijing would rather not make – and for wise economic and foreign policy reasons. Making such a choice would, I believe, effectively mark the end of China’s decade-long effort to positioning itself as an influential “helpful fixer” in the region – an outside power that seeks to broker peace deals and create a truly inclusive regional economic and security order.

Beijing’s objectives and strategies

Whereas in decades past the conventional wisdom in diplomatic circles was that China was not that invested in the Middle East, this has not been true since about 2012. From that time onward, China has invested considerable diplomatic energy building its influence in the region.

Beijing’s overall strategic vision for the Middle East is one in which U.S. influence is significantly reduced while China’s is significantly enhanced.

On the one hand, this is merely a regional manifestation of a global vision – as set out in a series of Chinese foreign policy initiatives such as the Community of Common Destiny, Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative and Global Civilization Initiative – all of which are designed, in part at least, to appeal to countries in the Global South that feel increasingly alienated from the U.S.-led rules-based international order.

It is a vision grounded in fears that a continuation of United States dominance in the Middle East would threaten China’s access to the region’s oil and gas exports.

That isn’t to say that Beijing is seeking to displace the United States as the dominant power in the region. That is infeasible given the power of the dollar and the U.S.‘s longstanding relations with some of the region’s biggest economies.

Rather, China’s stated plan is to promote multi-alignment among countries in the region – that is to encourage individual nations to engage with China in areas such as infrastructure and trade. Doing so not only creates relationships between China and players in the region, it also weakens any incentives to join exclusive U.S.-led blocs.

Beijing seeks to promote multi-alignment through what is described in Chinese government documents as “balanced diplomacy” and “positive balancing.”

Balanced diplomacy entails not taking sides in various conflicts – including the Israeli-Palestinian one – and not making any enemies. Positive balancing centers on pursuing closer cooperation with one regional power, say Iran in the belief that this will incentivize others – for example, Arab Gulf countries – to follow suit.

China’s Middle East success

Prior to to the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel, Beijing’s strategy was beginning to pay considerable dividends.

In 2016, China entered a comprehensive strategic partnership with Saudi Arabia and in 2020 signed a 25-year cooperation agreement with Iran. Over that same timespan, Beijing has expanded economic ties with a host of other Gulf countries including Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Oman.

Beyond the Gulf, China has also deepened its economic ties with Egypt, to the point where it is now the largest investor in the Suez Canal Area Development Project. It has also invested in reconstruction projects in Iraq and Syria.

Earlier this year, China brokered a deal to re-establish diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran – a major breakthrough and one that set China up as a major mediator in the region.

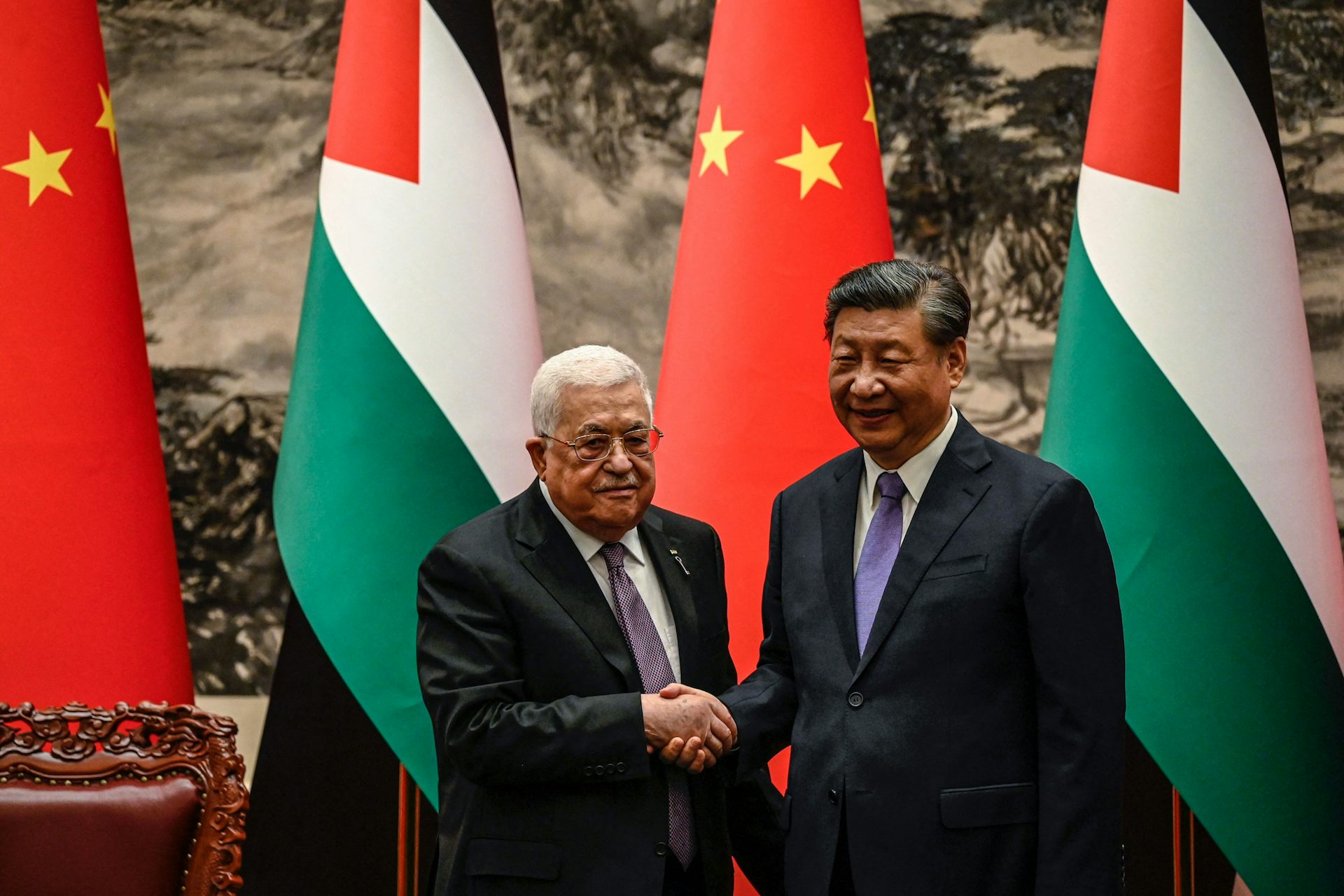

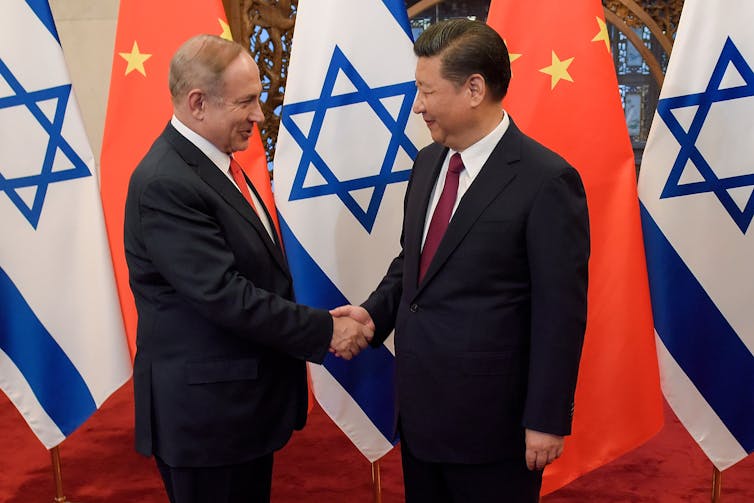

In fact, following that success, Beijing began to position itself as a potential broker of peace between Israel and the Palestinians.

The impact of the Israel-Hamas War

The Israel-Hamas war, however, has complicated China’s approach to the Middle East.

Beijing’s initial response to the conflict was to continue with its balanced diplomacy. In the aftermath of the Oct. 7 attack, China’s leaders did not condemn Hamas, instead they urged both sides to “exercise restraint” and to embrace a “two-state solution.”

This is consistent with Beijing’s long-standing policy of “non-interference” in other countries’ internal affairs and its fundamental strategic approach to the region.

But the neutral stance jarred with the approach adopted by the United States and some European nations – which pushed China for a firmer line.

Under pressure from U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, among others, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi reiterated China’s view that every country has the right to self-defense. But he qualified this by stating that Israel “should abide by international humanitarian law and protect the safety of civilians.”

And that qualification reflects a shift in the tone from Beijing, which has moved progressively toward making statements that are sympathetic to the Palestinians and critical of Israel. On Oct. 25, China used it veto power at the United Nations to block a U.S. resolution calling for a humanitarian pause on the grounds that it failed to call on Israel to lift is siege on Gaza.

China’s U.N. ambassador, Zhang Jun, explained the decision was based on the “strong appeals of the entire world, in particular the Arab countries.”

Championing the Global South

Such a shift is unsurprising given Beijing’s economic concerns and its geopolitical ambitions.

China is much more heavily dependent on trade with the numerous states across the Middle East and North Africa it has established economic ties than it is with Israel.

Should geopolitical pressures push China to the point where it must decide between Israel and the Arab world, Beijing has powerful economic incentives to side with the latter.

But China has another powerful incentive to side with the Palestinians. Beijing harbors a desire to be seen as a champion of the Global South. And siding with Israel risks alienating that increasingly important constituency.

In countries across Africa, Latin America and beyond, the Palestinians’ struggle against Israel is seen as akin to fighting colonization or resisting “apartheid.” Siding with Israel would, under that lens, put China on the side of the colonial oppressor. And that, in turn, risks undermining the diplomatic and economic work China has undertaken through its infrastructure development program, the Belt and Road Initiative, and effort to encourage more Global South countries to join what is now the BRICS economic bloc.

And while China may not have altered its maps of the Middle East, its diplomats may well be looking at them and wondering if there is still room for balanced diplomacy.![]()

Andrew Latham, Professor of Political Science, Macalester College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.