U.S. policies are opening a door for Chinese influence with Pacific Island states.

Editor’s Note: In rhetoric, the United States is reorienting its foreign policy around the challenge of China, but in practice the United States is abandoning many forms of influence in Asia. My Center for Strategic and International Studies colleagues Charles Edel and Kathryn Paik assess the U.S. relationship with the smaller Pacific Island countries and argue that changes in U.S. tariffs, aid, and other policies are allowing China to increase its influence at the expense of the United States. – Daniel Byman

For years, the United States has declared itself a “Pacific power,” yet in reality, the United States has treated the Pacific Islands—a vast region stretching from Papua New Guinea east past Hawaii—like a forgotten relative that is remembered only during times of crisis and then quickly overlooked. This neglect is now catching up to the United States as a resurgent and ever-opportunistic China is deftly filling this vacuum.

A belated push for reengagement over the past decade, including reopening the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) mission to the Pacific in Fiji and increasing diplomatic presence across the region, had begun to turn this tide. But recent policy moves risk cementing the Pacific Island states’ perception of the United States as an unreliable, fair-weather partner—a perception that dangerously undercuts U.S. security. Some U.S. officials’ rhetoric continues to speak of commitment, such as when Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth stressed the critical nature of Pacific U.S. territories at the “tip of America’s spear” for deterrence. However, the numbers reveal a worrying pattern that shows a lack of U.S. interest, undermining Washington’s ability to forge lasting partnerships and jeopardizing U.S. strategic interests in a region becoming increasingly critical to U.S. competition in Asia.

While Washington says it is committed to bolstering relations with Pacific partners, it is unilaterally disarming in its competition with China. Recent decisions to slash foreign aid, impose tariffs, eviscerate America’s media presence, and deprioritize climate change risk are rolling back those hard-fought gains. The proposed 90 percent cut to USAID programs translates to eliminating 5,800 out of 6,200 multiyear USAID contracts globally, a staggering $54 billion reduction. Additionally, 4,100 out of 9,100 State Department grants are on the chopping block, leading to a $4.4 billion decrease in programmatic funding.

For the Pacific, these cuts are particularly devastating. According to the Center for Global Development, the cuts amount to 100 percent of USAID country programming for Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Palau, Fiji, and the Solomon Islands. Even in the Compact of Free Association (COFA) nations, which provide crucial defense access for the United States across the northern Pacific in exchange for economic assistance through the COFA agreements, critical funding is being struck; the Palau Red Cross Society, for example, faces a loss of nearly $600,000 in humanitarian aid. More worryingly, programs tied to climate change—considered a top national security threat for the Pacific Islands—are among those most likely to be axed. A $2.5 million small grants program for tackling climate change has already been terminated, as was a $905,487 grant to support Pacific disaster response.

The administration’s “Liberation Day” tariff announcements have created further confusion and resentment. The United States runs a trade surplus with all but two Pacific Islands—Fiji (a $208 million trade deficit) and tiny Tuvalu (a $168,000 trade deficit). Yet nearly all Pacific nations have been hit with tariffs ranging from 10 percent to 32 percent.

The total two-way U.S.-Pacific trade is roughly $1 billion, a minuscule fraction of the more than $7 trillion in global trade the U.S. conducts. There is no “level playing field” to be had with these economies. As Fijian Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka put it bluntly, “We don’t have anything to counter with so we will have to weather the storm and roll with the punches.” This sentiment reflects a growing pragmatism among Pacific leaders who, seeing the U.S. withdraw aid and strong-arm them on trade, will look to other partners.

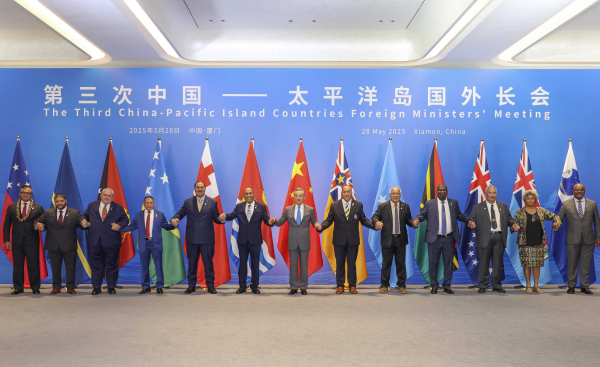

Beijing is capitalizing on Washington’s perceived retreat. In April 2025, China announced direct flights between Shanghai and Nadi, Fiji, with the Chinese ambassador noting that the U.S. trade war presented an opportunity for enhanced trade. In May, Beijing hosted Pacific foreign ministers in China for the first time, and during the summit unveiled plans for more than a hundred climate-related projects for the region—a stark contrast to the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and cuts to climate-focused grants.

The perception that the United States is uninterested in its Pacific partners is strong and growing. Reversing this trend requires immediate and decisive action. Based on our examination of the geopolitical landscape in the Pacific, here are five steps Washington can take immediately.

First, the United States should prioritize follow-through on existing commitments such as the Tuna Treaty, on which much of the maritime region depends, and implementing the COFA agreements. Furthermore, it can ensure the new U.S. embassies in Tonga, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu have resident ambassadors. In a region where Chinese diplomats often outnumber U.S. ones by 10 to one, pursuing at least a basic diplomatic presence is nonnegotiable.

Second, Washington can implement a realistic trade agenda. Even outside of this administration’s focus on tariffs, there are practical ways the United States can help bolster economic growth in the Pacific. Supporting a Pacific trade representative in the United States could open niche markets and create opportunities for both sides. Reconfiguring the Development Finance Corporation to work more effectively in the Pacific would also significantly bolster the U.S. economic toolkit.

Third, it can pursue new opportunities based on shared priorities. Drug trafficking and maritime domain awareness are growing threats in the Pacific that align with this administration’s security concerns. Leveraging U.S. law enforcement assets and the Coast Guard to provide training and assistance would address critical Pacific Island states’ needs while countering Chinese influence in the security space.

Fourth, the United States should capitalize on interest from partners and allies. Multilateral groupings like the Quad—with its focus on health, infrastructure, and connectivity—are perfectly suited for the Pacific. The trilateral U.S.-Australia-Japan partnership should also double down on critical infrastructure projects, an area in which China is making significant inroads.

Finally, the United States must embrace soft power for hard objectives. Foreign assistance is not charity; it is a strategic tool. Aligning with Pacific priorities on issues like health, infrastructure, and maritime security directly bolsters U.S. national security by strengthening U.S.-Pacific partnerships in a region where relationships are the currency of influence.

As Papua New Guinea Prime Minister James Marape stated after the tariff announcements, “Our trading partners in Asia … have treated Papua New Guinea with respect, honor, and fairness …. If the U.S. market becomes more difficult … we will simply redirect our goods to markets where there is mutual respect.”

Real influence in the Pacific stems from partnership and mutual respect, not unilateral dictates or withdrawals. As the State Department completes its foreign assistance review, now is the time for Washington to demonstrate genuine, sustained commitment to the Pacific, not just with words, but with actions that prove it is committed to an enduring presence.

– Charles Edel, Kathryn Paik, Published courtesy of Lawfare.