Vice President Joe Biden’s Cancer Moonshot Blue Ribbon Panel has released 10 recommendations to accelerate a new national effort “to end cancer as we know it.” These initiatives, focused mainly on the U.S., will almost certainly extend the lives of some cancer patients in the future.

However, cancer deaths worldwide are estimated to increase by over 50 percent between 2015 and 2030, mainly due to expanding and aging populations. We already have the knowledge and technology to reduce this toll for future decades without waiting for new breakthroughs.

About half of cancer cases and deaths worldwide are preventable. For instance, lung and liver cancer are the most common causes of cancer deaths around the world and cervical cancer is the fourth leading cause among women. And we already know how to prevent almost all of them.

Like many of my colleagues who study cancer prevention, I believe that scaling up existing preventive interventions and already available treatments over two to three decades could save millions of lives around the world.

Cut the number of lung cancer deaths globally

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death in the U.S. and around the world, killing over one and a half million men and women a year. But in American men, lung cancer death rates have fallen by about 40 percent over the past 25 years. In women, lung cancer rates have peaked.

That’s because the proportion of adults in the U.S. who smoke has decreased by about 50 percent since the 1960s, due to public education, indoor smoking bans and higher prices due to higher tobacco taxes. This reduction happened despite the ongoing, vigorous efforts of tobacco companies to combat these public health initiatives.

Similar reductions in France and South Africa have been achieved by increasing cigarette prices. However, the number of smokers is still increasing in countries such as China and Indonesia as tobacco companies seek new markets, and a demographic bulge of younger potential smokers enters adolescence.

The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control is the international blueprint on policies to reduce the uptake of smoking and encourage current smokers to quit.

The United States is one of only seven countries that has signed but not ratified the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. If our country is serious about cancer control, we should join the 180 countries that have ratified the convention.

Liver cancer: Focus on vaccines and curing hepatitis C infections

Liver cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death worldwide, killing about three quarters of a million people. It is the fifth most common cause of cancer death in the U.S.

The most common causes of liver cancer are infection with hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus. In some countries the dietary contaminant Aflatoxin, produced by molds that grow on stored grains or nuts, exacerbates the risk that hepatitis B infection will cause liver cancer.

Hepatitis B infection is almost entirely preventable by vaccination in infancy. In fact, an 80 percent decline in liver cancer rates has been observed in Taiwanese birth cohorts that have received the vaccination early in life.

While rates of infant hepatitis B vaccination are high around the world, many babies are still missing out. Universal vaccination would lead to a further decline in liver disease and liver cancer globally.

Hepatitis C causes about a quarter of liver cancer deaths worldwide. Curative therapies like the new drug Sovaldi may be another tool to prevent liver cancer. Researchers think that curing patients of their hepatitis C infection will prevent them from going on to develop liver cancer.

But the current cost of these drugs is a substantial barrier to their use in both lower-income countries and in the U.S.

However, in Egypt, public-private partnerships have made the drug available at less than 1/100th of their price in the United States. A vigorous international effort to use these new drugs to lower the number of infections would have a substantial impact on liver cancers caused by hepatitis C.

Heavier alcohol drinking also increases the risk of liver cancer (as well as cancers of the breast, esophagus, pancreas, colon and rectum). According to the World Health Organization consumption has been increasing in the two most populous countries, India and China.

Cervical cancer: Vaccines and Pap smears

Cervical cancer kills more than 250,000 women year worldwide, making it the fourth-leading cause of cancer death among women worldwide. In the U.S., however, it is 14th. From 1975 to 2012, the incidence of cervical cancer in the U.S. decreased by half, due to Pap smear tests screening and removal of precancerous lesions.

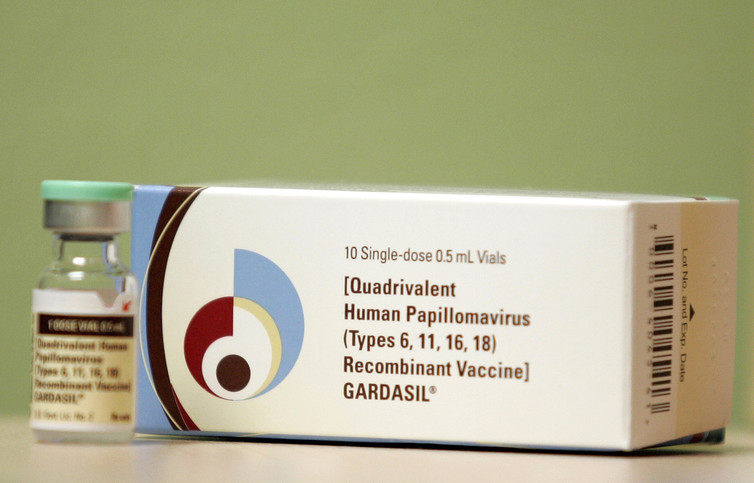

However, almost all cases of cervical cancer are due to infection with the Human Papillomavirus (HPV), and we now have a vaccine against the main strains of HPV. In theory, cervical cancer is almost entirely preventable if HPV vaccination before the onset of sexual activity is followed by screening in adulthood to detect precancerous lesions caused by virus strains not covered by the vaccine. Yet the vaccine is not available to most girls in the world.

The World Health Organization’s Expanded Program on Immunization ensures that 85 percent of the world’s young children now receive at least DPT vaccine against diptheria, pertussis and tetanus. This program created new distribution channels for vaccine and could be a model for increasing the number of prepubertal girls who receive the HPV vaccine.

Making sure that more women around the world receive the decades-old Pap smear testing or introducing the new HPV tests would also help reduce cervical cancer incidence.

We can also tackle childhood leukemia and breast cancer

In developed countries, the most common form of childhood leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia, is cured by conventional chemotherapy in over 80 percent of affected children. These life-saving, relatively inexpensive drugs have been available in the U.S. for decades. Yet in other parts of the world, most children with leukemia die because they do not receive treatment.

Drugs like Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors have decreased mortality from estrogen-fueled breast cancers in the developed world. Yet most women in the developing world with these cancers do not receive these inexpensive medications.

While leukemia and breast cancer require relatively sophisticated diagnostic and treatment infrastructure, they don’t require new treatments. The still-missing piece is the political will and funding to expand access to these long-established treatments.

Optimizing the technology and knowledge we already have

Pinning our hopes on new technologies isn’t the only way to reduce cancer deaths worldwide. A moonshot-level impact could be guaranteed just by ensuring the interventions and treatments we already know to be effective are deployed around the world.

Critically, we already have models that show how this can be done. Programs, such as The President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief and the Global Fund for HIV, TB and Malaria made lifesaving antiretroviral drugs available to millions of HIV patients by negotiating much lower drug prices. The programs also helped countries establish the necessary infrastructure to deliver the drugs and monitor patients.

There is much more we can do to prevent cancer in the U.S. Although smoking rates have done down, 17 percent of adults still smoke. Less than half of our teenage girls and boys received the recommended three doses of the HPV vaccine. Racial disparities still exist in access to early detection and treatment of cancers.

For the cancers we cannot prevent, we will always need new and better therapies. But we should not wait for future cures to do what we can to prevent cancer deaths around the world.

We can choose to prevent many cancers and cancer deaths globally. In the words of President John F. Kennedy in launching the first moonshot:

“because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone.”

David Hunter, Vincent L. Gregory Professor of Cancer Prevention, Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.