The Arctic is threatened by strong climate change: the average temperature has risen by about 3°C since 1979 – almost four times faster than the global average. The region around the North Pole is home to some of the world’s most fragile ecosystems, and has experienced low anthropogenic disturbance for decades. Warming has increased the accessibility of land in the Arctic, encouraging industrial and urban development. Understanding where and what kind of human activities take place is key to ensuring sustainable development in the region – for both people and the environment. Until now, a comprehensive assessment of this part of the world has been lacking.

More than 5% of the Arctic show signs of human activity

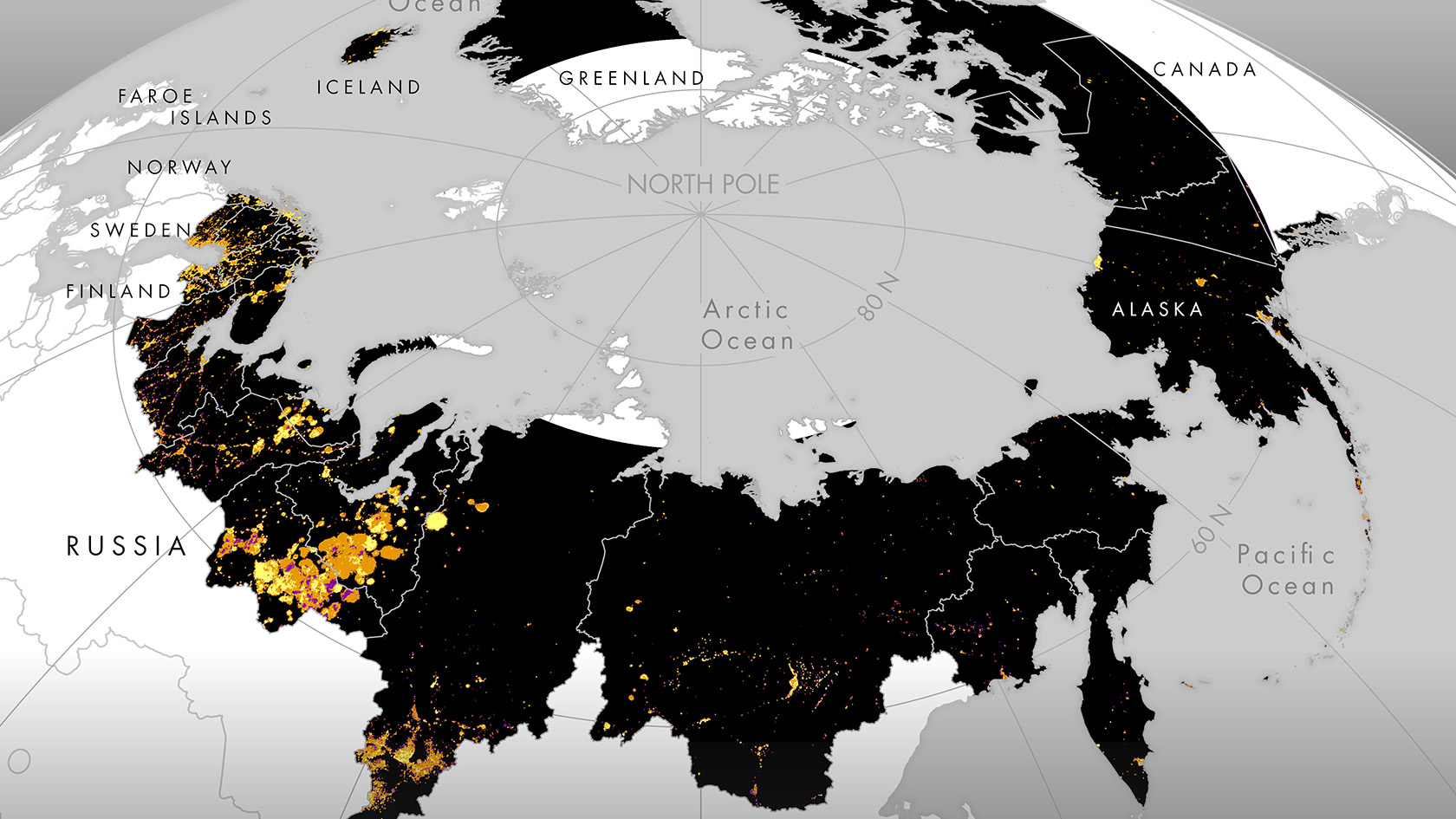

An international research team led by Gabriela Schaepman-Strub from the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Zurich (UZH) has now shed light on this question. Together with US colleagues from NASA and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the UZH researchers used data of nighttime artificial light observed from satellites to quantify the hotspots and evolution of human activity across the Arctic from 1992 to 2013. “More than 800,000 km2 were affected by light pollution, corresponding to 5.1% of the 16.4 million km2 analyzed, with an annual increase of 4.8%,” says Schaepman-Strub. With the new, standardized approach the researchers were able to spatially assess human industrial activity across the Arctic, independent of economic data.

The European Arctic and the oil and gas extraction regions of Alaska, USA, and Russia were hotspots of human activity, with up to one-third of the land area illuminated. Compared to these regions, the Canadian Arctic was largely dark at night. “We found that, on average, only 15% of the lit area in the Arctic contained human settlements, which means that most of the artificial light is due to industrial activities rather than urban development. And this major source of light pollution is increasing in both area and intensity every year,” says first author Cengiz Akandil, a doctoral student in Schaepman-Strub’s team.

Effects on terrestrial ecosystems and regional sustainability

According to the researchers, these data provide an essential basis for future studies on the impact of industrial development on Arctic ecosystems. “In the vulnerable permafrost landscape and tundra ecosystem, even just repeated trampling by humans, and certainly tracks left by tundra vehicles, can have long-term environmental effects that extend well beyond the illuminated area detected by satellites,” says Akandil.

The negative impacts of industrial activities and light pollution are absolutely critical for the Arctic biodiversity. For example, artificial light at night reduces the ability of Arctic reindeer to adapt their eyes to the extreme blue color of winter twilight, which allows them to find food and escape predators. It also delays leaf coloration and breaking leaf buds, which is critical for the Arctic species where the growing season is limited. Furthermore, human activities foster the expansion of invasive species in the Arctic, and oil and gas extraction frequently lead to environmental pollution – as does the mining industry, which is also expanding.

Documenting industrial activity is crucial for sustainable development

The effects of rapid climate change in the Arctic require local communities to adapt quickly, and the industrial development might further increase the need for adaptation – and enhance the costs on society and the environment. The direct impacts that human activity has on Arctic ecosystems could exceed or at least exacerbate the effects of climate change in the coming decades, the researchers estimate. If the growth rate of industrial development between 1940–1990 is maintained, 50–80% of the Arctic may reach critical levels of anthropogenic disturbance by 2050.

“Our analyses on the spatial variability and hotspots of industrial development are critical to support monitoring and planning of industrial development in the Arctic. This new information may support Indigenous Peoples, governments and stakeholders to align their decision-making with the Sustainable Development Goals in the Arctic,” concludes Gabriela Schaepman-Strub.