When the Conservative MP Nigel Evans was interrupted during a television interview in early September by an anti-Brexit protester, he criticised the “extremism” of Remainers. Back in February, the avowed Brexiteer Jacob Rees–Mogg warned that delaying Brexit would risk a surge in right–wing extremism. Others have also blamed Brexit for the rise of “extremist views” from both ends of the political spectrum – and complained that extremism is being encouraged from the top.

But the word extremism shouldn’t be used lightly. As Sara Khan – the lead commissioner at the Commission for Countering Extremism – said in July:

We shouldn’t lazily throw around the word ‘extremism’. We need to use it with precision and care.

In less turbulent times, this ambiguity in the meaning of extremism might not have been a big concern. However, considering the division in British society that’s been exposed and gradually deepened by Brexit, this remains a pressing problem.

The government officially defines extremism as the:

Vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs … calls for the death of members of our armed forces (are also) extremist.

According to a recent survey, 75% of public respondents find this definition “very unhelpful” or “unhelpful”. A recent study even showed that far–right groups with clearly dangerous ideology are using the definition to “prove” that they are not extremist.

These conceptual challenges are also reflected within the language of politics. In our recent analysis of British parliamentary debates between 2010 and 2017, we discovered a significant and worrying convergence between the terms “terrorism” and “extremism” to the point where they are increasingly being used interchangeably.

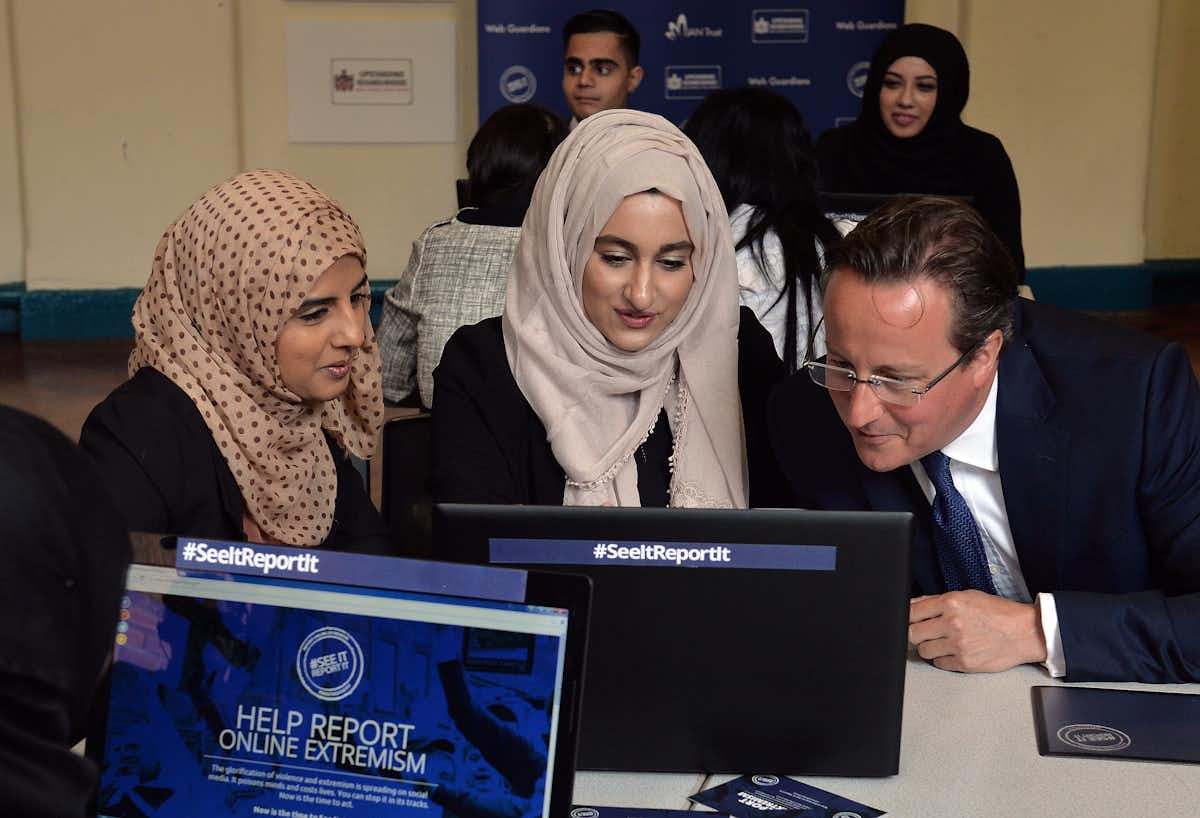

These terms have in many ways converged in political discourse replicating the same frames of reference for both concepts. Back in 2013, the then-prime minister, David Cameron, referred to the “extremist ideology that perverts and warps Islam to create a culture of victimhood and justify violence”. He argued that the UK “must confront that ideology in all its forms … and not just on violent extremism.”

More recently, the former home secretary, Sajid Javid, argued that extremism has “gone from being a minority issue to one that affects us all … and the way we all live our lives is under unprecedented attack”.

But extremism and terrorism should not be so simply interlinked.

Language matters

Extremism has tended to refer to both violent and non-violent forms of political expression, whereas terrorism is predominantly violent. To be an extremist could mean anything from being a nationalist, a communist, to being an animal rights activist – as long as this ideology is regarded as extreme relative to the government’s position. However, in the 1,037 parliamentary debates we analysed, terrorism generally referred to somebody involved in political violence.

Politicians from all parties increasingly stressed the transition from extremism to terrorism by using the terms “violent extremism” and “non-violent extremism” as a substitute for one another. Extremism was often framed as a pathway into terrorism.

But it’s worrying to extend the meaning of terrorism in this way to cover both violent and non-violent extremism. A person’s understanding of something shapes how they respond to it. So a child who views the sea as a playground will swim and play, whereas a fisherman will view it as a livelihood, casting his rod and nets accordingly. Put differently, the way extremism and terrorism are framed by politicians reflects and shapes how the police and security officials implement policy and how the public perceive these policies.

Targeting non-violent extremism as if it were terrorism is a problem because it directs counter-terrorism efforts against people’s political identities instead of political violence. Doing so closes off possible opportunities for dialogue.

Too much of an assumption

The area of counter-terrorism policy which this most closely relates to is the Prevent programme. The Prevent duty, which extends to teachers and university staff, seeks to safeguard against vulnerable individuals being drawn into political violence. According to 2017-18 official statistics, 7,318 people were subject to a referral under the Prevent programme, due to concerns that they were vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism. Of these, 14% were referred for concerns related to Islamist extremism and 18% for concerns related right-wing extremism.

Our analysis shows that what was previously solely considered “terrorism” is increasingly being framed interchangeably as “extremism”. And the meaning of non-violent extremism is gradually being reduced to the point where it can only be understood as terrorism. Under current counter-terrorism policy, certain public bodies are endowed with authority to monitor non-violent extremism as if it were terrorism.

All this reflects an underlying assumption that extremism always functions as a pathway into terrorism. This assumption has been used to legitimise counter-terrorism measures against both violent and non-violent extremism. These measures no longer focus on the behaviours or support for political violence – instead they focus on the ideologies which do not conform to the state’s definition of “normal” values.

Tackling extremism can help prevent terrorism, but only if the distinctions between them are properly understood. Conflating extremism and terrorism may even undermine counter-terrorism due to issues such as community alienation. That’s why challenging the assumption that all extremism leads to terrorism is important in improving policy responses to the very real threat of political violence.![]()

Daniel Kirkpatrick, Research Fellow, Conflict Analysis Research Centre, University of Kent and Recep Onursal, Assistant Lecturer and PhD candidate in International Conflict Analysis, University of Kent

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.