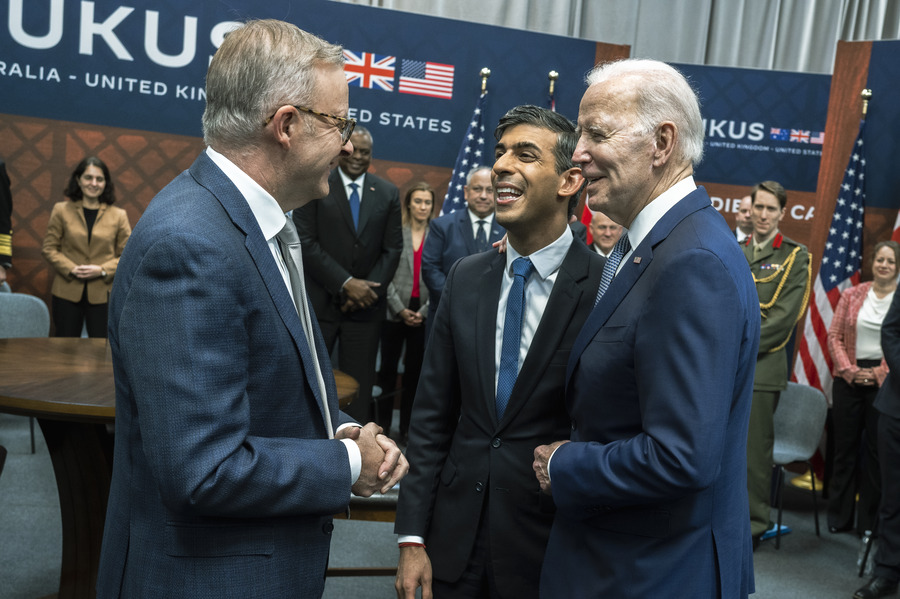

Few agreements rival the strategic, long-term relevance of the AUKUS (Australia, U.K., U.S.) security partnership. Signed in 2021 between Canberra, London, and Washington, the agreement has quickly become the centerpiece of U.S. plans in the Indo-Pacific, looking to procure a range of advanced defense capabilities focused on the AUKUS class of nuclear-powered submarines. Pitched primarily as a technology partnership, it aims to overcome technological and industrial challenges associated with building the capabilities themselves, and the attendant regulations on arms exports and technology sharing.

However, the foundations of the partnership are deeper: The fundamental strategic purpose of AUKUS is to bind close allies around a common agenda, pushing back against maritime coercion by hostile regional powers, specifically China. This rests on a shared commitment by the partner nations to act and operate seamlessly together, such as through the joint-crewing of submarines and interoperability for complex, shared capabilities. AUKUS is an agreement that is both strategic and constitutional at its heart, relying on a cohesive, integrated approach to security and deterrence to realize its broader ambitions.

In April, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell noted that AUKUS “is not a jobs program, [and] it is not a technology development program. Those are corollary advantages. This is a security partnership that is profoundly constitutional and has the potential to not only create fundamentally new realities on the ground … but also change the nature of the way each of our three countries operate together.”

Campbell’s comments recognize the depth of the U.S. commitment to this strategic partnership, but they also touch on a deeper point—one often overlooked in allied security strategy. How do constitutional and legal considerations bear on Anglo-American alliance commitments, and to what extent do they influence strategic thought and posture?

The constitutional foundations of war powers and American alliances have received greater attention in recent years. A new report—co-authored for the Centre for Grand Strategy at King’s College London by myself, Patrick Hulme, and Samuel White, with assistance from Matthew C. Waxman and Geoffrey S. Corn—looks to examine this question in depth. The report is centered around five short policy-relevant essays that explore how war powers frameworks may impact the deterrent or warfighting purposes of the AUKUS partnership, while raising broader questions about the constitutional dimensions of alliances more generally. The report examines how the war power operates in each AUKUS state, considering how these largely complementary and yet divergent constitutional structures may influence their states’ foreign policy making and alliance structures with regard to deterrence and warfighting. We focus our remarks specifically on the future strategic ambitions of the AUKUS partnership, with a particular emphasis on U.S. and wider allied interests in the Indo-Pacific, and offer policy recommendations to that end.

Constitutional Constraints in Practice

While the constitutional elements of the AUKUS agreement may seem abstract, they can have far-reaching consequences. President Obama’s “red line” regarding the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war demonstrates the gravity of constitutional constraints. The report’s essay on U.K. war powers opens with an examination of this incident, specifically the fallout from the decision by British Prime Minister David Cameron to hold a vote on joining the U.S.-led airstrike campaign in 2013. By late summer of that year, the U.S., Britain, and France were planning airstrikes in response to the large-scale use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government against civilians. Despite possessing the legal and constitutional power to use force without a debate or a vote in Parliament, Cameron lacked political room to maneuver; at the time he was governing at the head of a coalition between his own Conservative Party and a significant cohort of Liberal Democrat members of Parliament, which placed him in a more politically precarious position than subsequent interventions.

Nevertheless, given the nature of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s crimes, Cameron assumed he would win a vote if he called one, so he sought parliamentary approval for military action. In doing so, he exposed himself to significant risk, which only increased when the leadership of the opposition Labour Party—who had initially supported intervention—reversed course, adding pressure to Cameron’s political position in Parliament. On Aug. 29 2013, for the first time in more than two centuries and by only a narrow margin, the House of Commons voted against military action.

The Syria vote highlights many of the issues regarding the constitutional, legal, and political processes within allied nations regarding the power to wage war. At the time, it precipitated a rift between the United States and its closest ally, and led to lingering questions about the relationship between Anglo-American war powers arrangements and the credibility of these states’ alliance commitments. Specifically, the case demonstrates how questions about constitutional war powers regimes can lead to misunderstandings between allied governments, with significant strategic implications.

However, the Syria vote is but the most recent and clear-cut example of war powers issues impacting foreign policy. Glancing further back, one can see that war powers structures have often been central to pivotal events in world history and warfare. To take but two key examples, U.S. war powers constraints were a constant limitation on President Roosevelt’s freedom to directly enter World War II prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Equally, they were a serious consideration of the German Foreign Office’s calculations in 1940 when attempting to judge how the U.S. would react to a war in Europe.

Domestic Constitutional Structures

Our report therefore seeks to highlight these often-obscured dimensions of alliance politics, examining how the structure of a nation’s war powers procedures has an impact on that state’s international commitments and deterrence posture. The central argument is that knowledge, or lack thereof, of the constitutional and legal systems of allies can have important implications for what might otherwise seem like minor issues. The primary motivating question centered on how, and to what extent, constitutional limitations on the use of force exposed most clearly by the “Syria vote” raised the prospect of similar issues occurring for other Anglo-American alliance commitments, such as AUKUS. Given the increase in overt great power competition over the past few years, including a major war on the European continent and a swathe of new and complex military partnerships to bolster allied deterrence and warfighting power, this seemed like an issue worth interrogating. Underlying this is the question of long-term political commitments from allies, and the ways in which differences in war powers regimes can impact the effectiveness of alliances. While AUKUS has received broad bipartisan support in all three states since its inception, questions have been raised by the rise of isolationist presidential candidates in the U.S. as to the strength of these commitments, and the importance that future American administrations will continue to place on alliances. As such, examining the legal and political processes that permit or restrain these states when exercising the power to make war, and how this may impact an alliance such as AUKUS, is of clear and present relevance.

A comparative analysis of the AUKUS partners’ war powers processes reveals broadly similar arrangements but also peculiar divergences, which have the potential to impact allied security strategy if left unaccounted for in alliance thinking. Owing to their shared constitutional history, Britain and Australia employ similar procedures, although the British system has a far stronger tradition of parliamentary oversight and involvement. In Australia, broad constitutional powers are afforded to Canberra for the deployment of the Australian Defence Forces with a relative lack of legal restrictions and a broadly deferential tradition of political oversight. As a result, while questions may be raised about Australia’s continued political support of the AUKUS agreement if it does not live up to expectations, it is the least problematic of the three partners from a domestic constitutional perspective.

In contrast, despite the lack of a legal requirement to involve Parliament in the decision to use force, the British government’s expansive prerogative powers to make war are normally tempered by the close involvement of the House of Commons. While this results in greater parliamentary involvement and oversight than in Australia, the decision to use force in Britain is also more reliant on the particular composition of the House of Commons than is the case in either the U.S. or Australia. Equally, the personal judgment of prime ministers can have a clear impact on the decision to use force in Britain. Consider, for example, the decision to enter the second Gulf War in 2003, which was driven to a great extent by the prime minister’s personal convictions and judgment. While they are very different cases, the 2013 Syria vote and the Suez crisis of 1956 are also key examples of the personal judgment of prime ministers exercising a key influence on the decision to use force. It is no coincidence that these were both instances of tension between Britain and the United States.

Despite its nominally unconstrained image of an “imperial” presidency, the U.S. executive is more explicitly constrained by legislative limitations than is the case in either Britain or Australia. As commander in chief, the president possesses broad powers to act—and may take exceptional decisions if necessary—under Article II of the Constitution, yet presidents have often proved deferential to congressional will when using force. The struggle between these two branches over the nature and scope of the war power is at the core of the U.S. constitutional order and plays an important role in shaping its foreign policy. As such, the war powers regime in the United States is markedly different from either the British or Australian model in terms of its formal legal structure. This could pose complications for alliance commitments, as already alluded to in the World War II examples mentioned above, if it is not factored into allies’ calculations of U.S. foreign policy.

The repercussions of this difference can cut both ways. Consider the repeated rhetorical threats by former President Trump to withdraw the nuclear umbrella and U.S. support to NATO allies spending less than 2 percent of gross domestic product on defense, generating concern in European capitals in the run-up to the November election. While these threats are at one level deeply damaging to the alliance’s credibility and will pose serious concerns for alliance coherence, congressional support for the Atlantic Alliance will likely constrain the second Trump administration more than his rhetoric suggests. Indeed, a concerted effort against current or future isolationists’ plans to abandon certain allies, conducted through determined public political opposition to anti-NATO foreign policy decisions, would likely be effective in deterring a president from pursuing unilateral disengagement from European defense. The question would then be how an isolationist president manages a broadly pro-alliance-leaning Congress, and the impact this has on their deterrence signaling to both partners and adversaries.

Key Takeaways

One key takeaway from the report, therefore, is that while legal processes are important for how these states make war, they are often second-order questions that flow from initial political decisions. The most important constitutional constraints in all three states remain broadly political in nature, or at least concern the political interpretation and application of legal constraints. As a result, the legal and political elements of war powers frameworks should be recognized as interrelated, rather than exclusive. For instance, how these states incorporate the legislature into their decision-making processes can play a significant role in large-scale conflicts and formal warfare, as well as providing legitimacy for smaller-scale uses of force above the threshold of special forces operations. The willingness of the House of Commons or Congress to express its opinion on foreign policy, or the foreign policy leanings of a prime minister or president, are often far more relevant than legal conditions on the use of armed force—such as the U.K. “War Powers Convention” or the U.S. War Powers Resolution.

The rhetorical use of these legal mechanisms may aid political argument, but it is no substitute for members of the legislature actively choosing to hold the government to account over issues deemed impolitic or inappropriate. Given its deliberately bifurcated allocation of war powers in the U.S., it should be considered the most unusual actor among the triad, and attention should be focused on understanding how its constitutional structures may impact its commitments to AUKUS. More broadly, promulgating a greater awareness of internal processes for how each of the partners makes war, particularly their internal government-legislature relations, would certainly be beneficial in the long term.

Several conclusions flow from this in light of AUKUS, both legal and political. First, a strong political understanding of constitutional cultures and legal limitations is the most important aspect of how these war powers frameworks interact, preventing expectation gaps from emerging on key issues or the deployment of AUKUS capabilities. On the legal side, there should be internal—and perhaps public—clarity on the legal implications of procured capabilities, such as mixed-crew Virginia- or AUKUS-class submarines, to ensure a more cohesive posture among the AUKUS allies. This should be debated among the partner nations. In addition, given the breadth of AUKUS Pillar 2 capabilities, it is worth considering the threshold at which offensive gray-zone and asymmetric activities may breach sub-threshold competition and thereby require legislative debate or even authorization. This could help shape future escalation dynamics in the event of a conflict.

Furthermore, caveats, rules of engagement, and acceptable escalation dynamics regarding AUKUS capabilities must be acknowledged and formalized into legal standards to guide the partners in the event of a crisis. Finally, the three partners should work to minimize expectation gaps around these capabilities and preempt potential misalignment on the decision to use force to increase AUKUS’s deterrent effects. Fora such as the AUSMIN (Australia-U.S.) and AUKMIN (Australia-U.K.) ministerial bilaterals are good starting points for these discussions, and work should be done to build upon these.

On the political side, there should be greater dialogue on the constitutional dynamics of war powers frameworks, both within the individual states and between the partners themselves, regarding AUKUS and similar agreements. Specifically, there is a need for greater political alignment between the three partners over the informal, nonlegal standards that structure the war powers arrangements of each nation, such as how these powers are understood, interpreted, and applied by the government. If AUKUS is to realize the ambitions that have been set for it, the partners must ensure that potential constitutional gaps in their strategic deterrence and warfighting postures are closed as tightly as they can be. This is clearly a softer process than legal or regulatory alignment, requiring key individuals in each state to remain aware of the political processes by which their allies make decisions on war and foreign affairs, as well as maintaining an in-depth, up-to-date understanding of how the leaders conceptualize their political and constitutional requirements to exercise these powers. Alignment on—or at least awareness of—some of the issues outlined above could improve this. Although the use of force remains the sovereign decision of each state, cultivating a better understanding of how one’s allies make war can clearly and significantly improve collective deterrence, alliance reassurance, and warfighting capabilities across both existing and emerging partnerships.

– Daniel Skeffington is a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of War Studies at King’s College, London, working on the historical exercise of the war prerogative by the British government and its relationship to international law. He works as a Parliamentary Researcher to the Lord Stirrup KG, former Chief of the Defence Staff (2006-2010), and is a student contributor for Lawfare.