A group of researchers, led by a University of New South Wales (UNSW) sustainability scientist, have reviewed existing academic discussions on the link between wealth, economy and associated impacts, reaching a clear conclusion: technology will only get us so far when working towards sustainability – we need far-reaching lifestyle changes and different economic paradigms.

In their review, published today in Nature Communications and entitled Scientists’ Warning on Affluence, the researchers have summarised the available evidence, identifying possible solution approaches.

“Recent scientists’ warnings have done a great job at describing the many perils our natural world is facing through crises in climate, biodiversity and food systems, to name but a few,” says lead author Professor Tommy Wiedmann from UNSW Engineering.

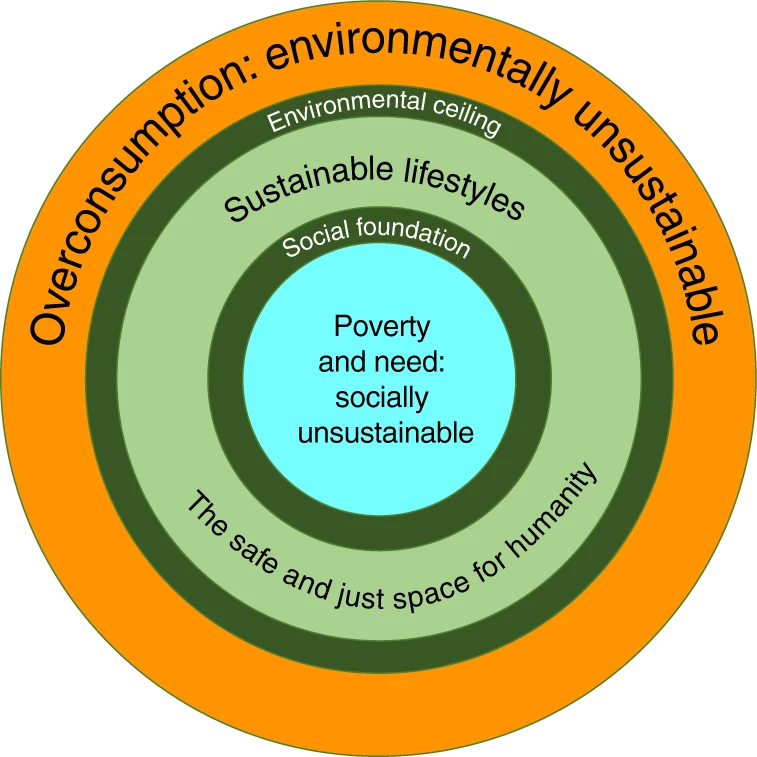

“However, none of these warnings has explicitly considered the role of growth-oriented economies and the pursuit of affluence. In our scientists’ warning, we identify the underlying forces of overconsumption and spell out the measures that are needed to tackle the overwhelming ‘power’ of consumption and the economic growth paradigm – that’s the gap we fill.

“The key conclusion from our review is that we cannot rely on technology alone to solve existential environmental problems – like climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution – but that we also have to change our affluent lifestyles and reduce overconsumption, in combination with structural change.”

During the past 40 years, worldwide wealth growth has continuously outpaced any efficiency gains.

“Technology can help us to consume more efficiently, i.e. to save energy and resources, but these technological improvements cannot keep pace with our ever-increasing levels of consumption,” Professor Wiedmann says.

Reducing overconsumption in the world’s richest

Co-author Julia Steinberger, Professor of Ecological Economics at the University of Leeds, says affluence is often portrayed as something to aspire to.

“But our paper has shown that it’s actually dangerous and leads to planetary-scale destruction. To protect ourselves from the worsening climate crisis, we must reduce inequality and challenge the notion that riches, and those who possess them, are inherently good.”

In fact, the researchers say the world’s affluent citizens are responsible for most environmental impacts and are central to any future prospect of retreating to safer conditions.

“Consumption of affluent households worldwide is by far the strongest determinant – and the strongest accelerator – of increased global environmental and social impacts,” co-author Lorenz Keysser from ETH Zurich says.

“Current discussions on how to address the ecological crises within science, policy making and social movements need to recognize the responsibility of the most affluent for these crises.”

The researchers say overconsumption and affluence need to be addressed through lifestyle changes.

“It’s hardly ever acknowledged, but any transition towards sustainability can only be effective if technological advancements are complemented by far-reaching lifestyle changes,” says co-author Manfred Lenzen, Professor of Sustainability Research at the University of Sydney.

“I am often asked to explain this issue at social gatherings. Usually I say that what we see or associate with our current environmental issues (cars, power, planes) is just the tip of our personal iceberg. It’s all the stuff we consume and the environmental destruction embodied in that stuff that forms the iceberg’s submerged part. Unfortunately, once we understand this, the implications for our lifestyle are often so confronting that denial kicks in.”

No level of growth is sustainable

However, the scientists say responsibility for change doesn’t just sit with individuals – broader structural changes are needed.

“Individuals’ attempts at such lifestyle transitions may be doomed to fail, because existing societies, economies and cultures incentivise consumption expansion,” Professor Wiedmann says.

A change in economic paradigms is therefore sorely needed.

“The structural imperative for growth in competitive market economies leads to decision makers being locked into bolstering economic growth, and inhibiting necessary societal changes,” Professor Wiedmann says.

“So, we have to get away from our obsession with economic growth – we really need to start managing our economies in a way that protects our climate and natural resources, even if this means less, no or even negative growth.

“In Australia, this discussion isn’t happening at all – economic growth is the one and only mantra preached by both main political parties. It’s very different in New Zealand – their Wellbeing Budget 2019 is one example of how government investment can be directed in a more sustainable direction, by transforming the economy rather than growing it.”

The researchers say that “green growth” or “sustainable growth” is a myth.

“As long as there is growth – both economically and in population – technology cannot keep up with reducing impacts, the overall environmental impacts with only increase,” Professor Wiedmann says.

One way to enforce these lifestyle changes could be to reduce overconsumption by the super-rich, e.g. through taxation policies.

“‘Degrowth’ proponents go a step further and suggest a more radical social change that leads away from capitalism to other forms of economic and social governance,” Professor Wiedmann says.

“Policies may include, for example, eco-taxes, green investments, wealth redistribution through taxation and a maximum income, a guaranteed basic income and reduced working hours.”

Modelling an alternative future

Professor Wiedmann’s team now wants to model scenarios for sustainable transformations – that means exploring different pathways of development with a computer model to see what we need to do to achieve the best possible outcome.

“We have already started doing this with a recent piece of research that showed a fairer, greener and more prosperous Australia is possible – so long as political leaders don’t focus just on economic growth.

“We hope that this review shows a different perspective on what matters, and supports us in overcoming deeply entrenched views on how humans have to dominate nature, and on how our economies have to grow ever more. We can’t keep behaving as if we had a spare planet available.”